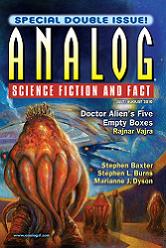

“Dr. Alien’s 5 Empty Boxes” by Rajnar Vajna

“Dr. Alien’s 5 Empty Boxes” by Rajnar Vajna

“The Bug Trap” by Stephen Burns

“Project Hades” by Stephen Baxter

“Fly Me to the Moon” by Marianne Dyson

“The Android Who Became a Human Who Became an Android” by Scott William Carter

“The Long Way Around” by Carl Frederick

“Questioning the Answer Tree” by Brad Aiken

“The Single Larry Ti, or Fear of Black Holes and Ken” by Brenda Cooper

Reviewed by Carl Slaughter

The main character in “Dr. Alien’s 5 Empty Boxes,” by Rajnar Vajna, is not named Dr. Alien. That’s his nickname. He’s a shrink who treats aliens. Men in black arrive at his house after his car is bombed outside his clinic. The MIB have a lot of intriguing questions about the aliens who financed and staffed his clinic, his trip to their ship, and the three mysterious patients he treated on board. Everyone on the ship is an alien to him, but the three patients are aliens to the aliens. The MIB are especially curious about the abilities of these patients and obviously have a theory that one or more of the patients is linked to the murder attempt. After the MIB meeting, his employers deliver yet another patient alien to them. This one is what Earthlings would perceive as a robot and must be assembled from the contents of the 5 boxes. Between the very entertaining MIB scene and the boxes scene, there’s a large amount of space devoted to his interaction with some interesting aliens. A feast for alien fans, as well as character development fans. Meanwhile, the local police are investigating patients and angry clinic neighbors for suspects. As well, one of his alien patients is in a vegetable state. When the boxes arrive, the shrink seems to forget that only the day before, someone tried to assassinate him and government agents gave him the third degree. This is hardly plausible and even the distraction of the boxes can’t justify it. There’s also a bit of a plausibility problem with the MIB asking the main character about the special powers of aliens, since he’s a shrink rather than a biologist or a physicist.

The storytelling would be much less enjoyable without the author’s liberal wit. Hardly a paragraph fails to include a very effective wisecrack from the main character or a culture clash/communication gap between species. For hard science fans, there’s plenty of hard science blended into the plot, activities, and characters. The identity and motive of the would-be assassin is revealed and all the characters and elements of this sophisticated and well-crafted story are wrapped up with a happy ending.

Remember that infamous opening sentence so often ridiculed in literature and creative writing classes as a classic example of how not to start a story? “It was a dark and stormy night.” “The Bug Trap,” by Stephen Burns, gets off to a similarly bad start. “Reflections from neon and LEDon lights washed across the rain-soaked night streets like smears of wet paint.” Here’s a taste of the style:

“Posto handle: Glyph. Age: twenty-seven. Employment record: spotty. Legal history: problematic. Prospects: not to be envied.” Another taste: “As a posto I’m an enthusiastic malcontent who mixes street art, graffiti, sloganeering, muckraking, ad-jacking, and the politics of outrage as a vocation. In other words, a dedicated semi-pro troublemaker. I’d made myself a whole pile of it this time. My mentor, old Slippery Jone, Mistress of the Subversive Koan, always said that if they’re not trying to find you to buy you off or work you over, then you’re not trying hard enough. Pride points for success, except that I’d managed to piss off both sides of an issue badly enough that both wanted me bagged and slabbed.”

If you consider 20,000 words of this a treat, read on. If not, move on. The first 2000 words comprise a back street escape. Then we finally get to the premise. Maybe this hokey introduction will persuade you to stop reading:

“Members of an alien race who called themselves the B’hlug had come to our solar system and taken up residence on Venus, that planet chosen because we didn’t seem to be using it, and it was comfortably out of bomb range. The B’hlug declared themselves a peaceful and benevolent race, and looking forward to having some earthlings come on out to check out the very nice place they had built for us so we could all get to know each other better.”

Still determined because you’re a diehard alien-meets-Earthling fan? Try this 72 word obstacle course of a sentence:

“Never ones to scruple at such charming niceties as logic, fairness, intellectual honesty, or any of the other stains they wanted washed out of their concept of a proper society, they and their darlings immediately began seizing power, blasting themselves upward on a blaring cacophony of shrieking propaganda, gibbering hysteria, and extravagant threats calculated to make any fence sitters on the alien issue stain their shorts and fall off on their side.”

No matter how forgiving you are, surely you’ll give up before you get to the end of this sentence:

“The government line was so luridly cartoonish it had to be a lie, meaning the Bugs were probably not the slavering baby-eaters and virgin-defilers certain fact-impaired media outlets insisted they were, even without a single chewed baby or weepy deflowered virgin to back up their recitations of official talking points.”

Okay, Okay, you just gotta know what happens. The self-confessed troublemaker has no place left to run except into one of the teleportation booths. Because of mass xenophobic paranoia, very few people have accepted the invitations, so his strategy of last resort is risky. Let’s pause right here and say that this part of the premise requires an awful lot of suspended disbelief. Thanks to science fiction, Earthlings are fascinated with the idea of meeting extraterrestrials. So lots of people would have gotten into those booths one way or another. Well, when our interplanetary traveler first meets an alien facilitator, it is assuming the form of Gumby. That’s right, Gumby. Then a Martian from the Tim Burton movie. Then Princess Leia, then Mr. Spock, then Tommy Lee Jones from Men in Black, then the Terminator. Finally the Scarecrow from The Wizard of Oz. (Later in the story, the alien turns into Tinkerbell, then Kermit the Frog. No, I’m not making this up.) The Scarecrow offers him two doors. One door takes him back to Earth. The other destination is not revealed to him. He chooses the mystery door. Then the plot switches from Alice in Wonderland to Mad Max meets Monster Inc. A surprise happy ending. Let’s just say this type of story requires a special appreciation.

The first 1300 words of “Project Hades,” by Stephen Baxter, involves 5 characters introducing each other in a pub. Sprinkled throughout the conversations are a few sentences worth of premise. The next scene is a shorter version of a similar scenario. Three people talking in an underground military bunker and a bit more of the premise revealed. Project Hades is a joint British-American project. They are about to set off a bomb deep underground. Somehow, the detonation will end the Cold War. But an anomaly keeps occurring near the project, a geologist is concerned about instability, and angry locals are planning a protest. And the 8 people appear to be on course for an unplanned encounter. So even if the story sleepwalks to this point, surely it can only get better. Wrong. The story shuffles along zombie-like for another 1800 words with an awful lot of chatty conversation and only a crumb of additional premise. Then some philosophical dialog. Oh, eventually all the pieces of the puzzle are revealed. Eventually the various characters interact intensely, eventually subplots interlock into an ambitious plot. Indeed, eventually all hell breaks loose, on more than one front. And the premise involves plenty of plausible hard science. But the plot belongs in a B movie, the dialog gets cornier and cornier, some of the characters get more and more cartoonish, scenes unrelated to the plot fill large amounts of space and deflate carefully built intrigue, the presentation relies heavily on explanatory dialog where narration would have been the better tool, much of the vocabulary will be familiar only to British readers, and the story is excessively long. So either save yourself 28,000 words or do an awful lot of skimming.

The main character in “Fly Me to the Moon,” by Marianne Dyson, is a retired Apollo pilot with Alzheimer’s living in a retirement home. He insists his name is a secret, takes great care to avoid alleged lurking reporters, and reacts vehemently whenever the Russian space program is mentioned. A current Apollo mission is in trouble and he’s determined to come to the rescue. Of course, the retirement home staff don’t take him seriously. But one of them, namely the one who plays computerized flight simulation games with him, soon discovers the truth and eventually discovers why his identity is a secret. Meanwhile, the retired pilot saves the day. Wonderful story, familiar plot, new twist. Lots of details that only someone very familiar with a space flight program could supply. Written by a relative of the first director of the Johnson Space Center.

Here’s the science premise for “The Android Who Became a Human Who Became an Android,” by Scott William Carter: “Biological Imprinting Procedure. You grow a biosen[tient] in the lab, then use microlasers to imprint the same memories and thought patterns as the android.” The story is jazzed up with plenty of futuristic gadgetry, techno lingo, and alien encounters, but the only science essential to the plot, and the only original plot element, is the android factor. The rest of the plot is just another one of those old-flame-returns stories. To make the story all the more typical, the old flame is a former prostitute, the ex boyfriend is a private detective, and they are looking for her missing rich husband. The husband is the android who became a human who became an android. Other than the clever android angle, this one isn’t any better or worse than the other million of these stories.

“The Long Way Around,” by Carl Frederick, is a lunar station story. A new vehicle from Australia, shaped like a kangaroo and nicknamed Skippy, hops instead of crawling. The passengers experience highway, hardware, and astrophysics problems on a worst case scenario scale. Loads of interconnected and interacting hard science, but the plot and characters aren’t as interesting as in the author’s previous stories in this magazine..

“Questioning the Answer Tree,” by Brad Aiken is about politically correct medical protocol in the future. Doctors diagnose strictly by machine and recite prepared answers to questions from patients. Touching a patient or deviating from the ‘answer tree’ could result in a lawsuit. Violate the code, no matter how flawed and impersonal it might be, uniforms haul you away in handcuffs in full view of the media. Of course, an underground movement develops. I’m afraid this story doesn’t quite create the thick, suffocating atmosphere needed for a political correctness story to be powerful. The dreary life and agonizing decision making of the main character far overshadows the inadequate dystopian setup. All characters other than the main character are essentially cameos, so character interaction is minimal. And the science element receives very little attention. An enormous amount of unused potential here. Big disappointment.

“The Single Larry Ti, or Fear of Black Holes and Ken” by Brenda Cooper, is a science on trial drama. Environmental problems create distrust of science. The current hysteria is over whether Moon-based research will accidentally create a miniature black hole that will swallow the Moon. The fear is based on a one time tiny incident at the Large Hadron Collider. A science court will rule on whether to shut down the project. The two chief characters are ex-spouses, one promoting fear, the other insisting the likelihood doesn’t justify the loss of benefits. We’re a third into the story before anyone opens their mouth and nearly half into the story before anyone says anything significant to the plot. I’m afraid this story is more courtroom atmosphere than courtroom dialog. Discussion of hard science in action is a few sentences.