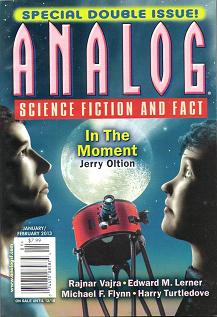

Analog, Jan-Feb, 2013

Analog, Jan-Feb, 2013

This issue of Analog contains a diverse selection of fantasy & SF stories. All of the authors have a long history of producing award-winning work, and that excellence is displayed throughout this issue.

“The Woman Who Cried Corpse,” by Rajnar Vajra, reads like a cross between a spy thriller and a treatise on temporal theory and sub-atomic physics, topics I enjoy but others might not. The author is an experienced writer with several awards, and the story’s subject reflects his eclectic background.

Overall the tale reads quite well. I especially liked the first half when Ali and her daughter, Glory, are trying real hard to not get killed by mysterious people trying to kidnap them. It seems that Ali’s mother died three times, all under really strange circumstances that caught the attention of both National Security and a terrorist group. At first the story rushes forward, keeping the reader a bit breathless and wanting to know what happens next. Then a large chunk of this story devolves into detailed pontifications about Harmonic Theory and its possible effects on movement through time. Ali does get to meet a younger version of her now dead mother, an experience that leaves her quite befuddled. But the ending fizzles out as Ali’s mother explains everything. Great first half with lots of action and tension, yet the second half, although intellectually intriguing, lacks the oomph of the first part.

Edward M. Lerner’s “Time Out” is a scientific-discovery mystery that runs smack into the dilemma of the butterfly-effect and the classic time-travel grandfather paradox. Peter is a disgraced felon handyman English major who trolls Home Depot parking lots early in the morning for any cash work he can find. Then Jonas, a scientist with a strong difference of opinion with the National Science Foundation, hires him to do general handiwork around his lab. Jonas is deep into time paradox research, trying to prove that effect can occur before cause.

The story is told from Peter’s perspective, like Igor telling the story of Frankenstein. Except, in this case, the true Frankenstein is the future itself, or at least the fear of it that drives well-meaning people to second guess their future-selves.

Peter inadvertently helps Jonas figure out how to send items into the future. Then Jonas’ future-self begins sending items back, followed by stock market and racing tips and warnings about what not to do. Jonas’ money troubles end, but his expectations grow until he can’t imagine why his future-self won’t alert him to pending disasters so he can warn people. All of this makes Peter’s head hurt—time travel theories, butterfly-effects from decisions made, Jonas’ increasingly cranky personality, especially when some of the tips turn bogus. In spite of his own warnings, Jonas bulls ahead, believing he knows better than his future-self. Ultimately, Peter’s greatest fear is proven correct—he is the butterfly that set all of Jonas’ time-travel madness in motion and shows that knowing the future doesn’t lead to better choices. All it does is scramble the timeline into a hopeless mess. A good read.

“The Exchange Officers,” by Brad R. Torgersen, reminds me a bit of a Flash Gordon yarn, except in this case it’s two warrant officers operating immersive remote robots to fight off a dozen Chinese marines trying to commandeer a U.S. orbital defense platform. The author, himself an Army Reserve Chief Warrant Officer, has won numerous awards for his work, a number of them military themed. The story is fast paced, easy to follow, yet rich with details reflective of the author’s own military experience. It’s a fun read.

Robert Scherrer’s “Descartes’s Stepchildren” asks that ageless question–should research be pursued regardless of the consequences? The power of science to change the world is great, both for the better and the worse.

Are all humans self-aware? John, a neuro-research scientist, develops an MRI test that locates the brain center of consciousness and learns that 20% of all humans are Blanks, technically not self-aware. His colleagues reject him and his results but society embraces it and turns upon the Blanks, adults and children alike. The story raises the specter of segregation driven by genetic testing or brain-scan results. Yet, ultimately aren’t all people equally worthy of the same love and acceptance as anyone else? For me the ultimate question is are we human because of how we take care of each other or due to some objective measure of what we are? I would choose the former, but what choice does John make?

“Buddha Nature,” by Amy Thomson, explores the nature of what it is to truly be human. Imagine a New England monastery filled with engineers and computer scientists looking for enlightenment. Into this comes a robot, calling itself “Raz,” also seeking enlightenment. Can a machine be self-aware, and, if it downloads itself into the Internet, has it realized reincarnation? This story is a cross between SF and philosophy, but then I would argue that all good SF does just that. In truth, how we treat other sentient beings will be the ultimate measure of us as human beings. A thought-provoking read.

Kyle Kirkland’s “True to Form” reminds me of a Sherlock Homes murder mystery set in a future where human-looking mechs work among us. Mechs are vat-cloned humans that lack a critical gene-set thereby robbing them of being self-aware. Society has taken a long time to accept mechs, but now a Senator threatens to undo all that. Her strident demands for greater limitations on the industry threaten a lot of people of power and influence, including someone who’d learned how to tweak mech programming to make them virtually indistinguishable from humans. Then the Senator is killed, poisoned by a drug that wasn’t capable of harming a human.

Cal was once an excellent pharmacologist, until a gambling addiction dropped him into abject poverty. But someone thinks he once worked with the man who may have managed to arrange the Senator’s death. As he’s reluctantly drawn into the chase, he gets lucky and survives an attempt on his life. Now he has to figure out who is truly trying to protect him and who is trying to poison him as he fights his way out of years of lethargy to figure out how mechs are being changed and how the drug killed the Senator. And whether people he once thought were friends were in reality modified mechs. Very enjoyable.

“In the Moment,” by Jerry Oltion, tells of the night the world could have ended when a comet approached impact with the Moon. Would it hit? Would it miss or just graze the lunar mountaintops? No one knew for sure and the world held its collective breath in fear and anticipation. In those moments, when “tomorrow” no longer exists, two amateur astronomers forget their teenage nervousness and recognize their attraction to each other. The comet misses, the world goes on, but love blooms and the world will never be the same for this young couple. A poignant tale.

John G. Hemry’s “The War of the Worlds, Book One, Chapter 18: The Sergeant-Major” is a deliciously sarcastic rendition of H. G. Wells’ classic story. A small 19th century British force defeats a 100 foot tall Martian tripod death machine using only rifles, bayonets and a modified tiger trap, all by the book, of course. Only the British can “go where they want, when they want, and in general act as lords of all creation,” so obviously “the Mars people must be bleeding sods to think they’re British!” Exquisite!

“Neighborhood Watch,” by H.G. Stratmann, presupposes that great SF writers possess rudimentary telepathic abilities which allow them to sense the multitude of other sentiences in the Solar System. To protect themselves from the violent non-intelligence of humans, the other races hide behind elaborate camouflage technologies to fool human observations. However, human space exploration is getting dangerously close to discovering the real truth about their neighbors. The Cereal killers of Ceres, a group mind that once before wiped out all intelligent life on Earth by sending an asteroid crashing into the planet 65 million years ago, wants to do the same again. But some Martians have a different idea. Being partners might be the best way to civilize humans. A light-hearted fantasy tale.