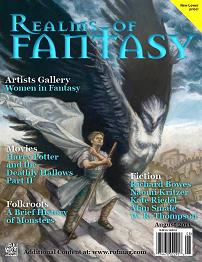

Realms of Fantasy, August 2011

Realms of Fantasy, August 2011

“The Progress of Solstice and Chance” by Richard Bowes

“Isabella’s Garden” by Naomi Kritzer

“Collateral Damage” by Kate Reidel

“Snake in the Grass” by W. R. Thompson

“Leap of Faith” by Alan Smale

Reviewed by John Sulyok

Richard Bowes – “The Progress of Solstice and Chance”

Have you ever wondered how the other half lives? And by the “other half” I mean the living embodiments of intangible concepts like Chance and Fate, or the Solstice. Richard Bowes has in “The Progress of Solstice and Chance,” an allegorical tale about the true lives of those we admire. The story’s primary focus is on Solstice, the daughter of the Queen of Summer and the King of Winter. However, the tale is less about her than it is about those around her, from her metaphorical family to the humans who look upon her from the periphery of their mortality.

Bowes’ prose reads like the literary equivalent of golden honey or sweet syrup, deftly flowing in a fluid progression from one paragraph to the next. However, when a reader is enveloped in a new fantastical world, with rules, terms, and characters out of the ordinary, a period of acclimatization in shallow waters is helpful. Here, the narrative plunges the reader into the deep end, which is not murky, but rather blindingly bright. Nevertheless, calmer waters wait beyond the opening section.

Thereafter the story plays out with Solstice bearing witness to the inner workings of her less-than-perfect family, including a love-triangle, and the ways in which humans have perceived them from antiquity to days yet-to-come. It reads as a fairy tale or parable, but ultimately has little to teach or excite the reader.

Naomi Kritzer – “Isabella’s Garden”

Naomi Kritzer’s “Isabella’s Garden” is a light-hearted, charming, and whimsical tale about the power of unbridled imagination. Isabella is a little girl with big determination – to plant anything and everything she can get her hands on. And with two wonderful parents encouraging her green thumb, an unreserved sense of love permeates the narrative, showing off Kritzer’s joy for writing.

Isabella has planted everything from “punkmins” to “moaning glowies,” but what will happen when she begins to experiment with other things, like jelly beans? It’s definitely worth finding out, and sharing with your kids.

Kate Riedel – “Collateral Damage”

“Collateral Damage,” the title of Kate Riedel’s story, is employed in its strictest sense as an unintended event, which in this case involves a temporal anomaly hounding a quiet ranch family. The story’s logline: “Which hurts more? To wait for someone who never comes back, or to wait for someone who comes too late?” hints at a heart-wrenching situation leading to a dramatic conclusion. Unfortunately, the story itself never reaches such an emotional climax. This, however, should not keep one away from reading the story of sisters united after four decades.

The narrator is Martha, a cynical grandmother frustrated with a life whiled away – or knitted away – because of her homebody of a husband Robert. The story quickly takes a sidestep though, as a neighbour’s daughter goes missing in a snowstorm. While a search party is assembled, Robert makes a discovery: Martha’s long-lost sister Peggy has materialized out of thin, cold, air and hasn’t aged a day beyond the fifteen years she was when she disappeared in a similar snowstorm over forty years earlier. From this point, the focus is on the reassembling of the family and what should be done with Peggy.

The dialogue feels like a private family conversation, except it’s somebody else’s family, leaving the reader feeling out-of-the-loop; at times confused, at others guilty. This should not be mistaken as a negative, however, as it feels authentic and far from expository. Yet there are instances in which the focus of the narrative jumps around like it too is caught in a temporal anomaly, although this could be perceived as the stream-of-thought narration by a grandmother.

The finale brings the story to a close, but leaves many questions, not simply unanswered, but unexplored. It will leave you wanting more, though not at the end, but in the middle.

W. R. Thompson – “Snake in the Grass”

Following his father’s death, Fred Larabie is left with a few questions in W. R. Thompson’s “Snake in the Grass.” Adrift in a sea of emotions, Fred feels lost for meaning. He could have guessed his father had relationships prior to meeting his mother, but learning of a long-lost step-brother solidified Fred’s assumptions that he could never live up to his father’s idea of an ideal son. How to make one’s father proud and living up to expectations is at the core of this story.

Fred soon meets the titular snake in the grass; except their first meeting is in a dimly lit booth in a bar as Fred looks to drown his sorrows in drink. The snake (and yes, he is whom you think!), ever the charmer, offers Fred happiness under the usual terms. With nothing to lose, and nothing to live for, Fred quickly agrees.

What follows are a house, a girl, and an apple tree all under a sky twicely lit by both the sun and a Betelgeuse gone supernova. Fred and the snake exchange smarmy comments and heartfelt guidance as they come to terms with their daddy-issues – because Fred isn’t the only one trying to be what his father wanted him to be.

Alan Smale – “Leap of Faith”

Alan Smale’s “Leap of Faith” mixes a common fantasy aesthetic with Biblical mythos in an intriguing way. Unfortunately the execution falls far short of expectations and does little to encourage a reader to proceed through the story.

Set in Shadom, a Middle-Eastern style desert town, the focus is on Levi, a man who wanders high and low in the pursuit of God. His family consists of his frustrated wife Rebekah, and daughters Deborah and Leah – none of whom are particularly happy with his long absence of seven months, nor his return. Little is done in his favour by the guests he brings home: two white- and blue-skinned angels seeking sanctuary.

While the premise would allow for a great yarn, which could work interesting allegorical concepts into the fold, the story is little more than a series of events that lead to an anti-climactic conclusion. Neither do the prose nor dialogue help matters as both are disjunctive in their use of antiquated phrasing and modern colloquialisms. The characters simply do not act the way one would expect for the time; the women are exceptionally feminist, an anachronism to say the least.

While some of the concepts within can be explained away as alternate-reality, it would only serve as an easy excuse for what is lacking.