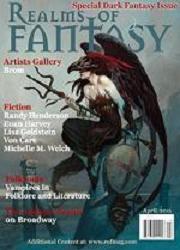

Realms of Fantasy, April 2011

Realms of Fantasy, April 2011

“A Witch’s Heart” by Randy Henderson

“The Sacrifice” by Michelle M. Welch

“Little Vampires” by Lisa Goldstein

“By Shackle and Lash” by Euan Harvey

“The Strange Case of Madeleine H. Marsh (Aged 14 ½)” by Von Carr

Reviewed by Caroline E. Willis

“A Witch’s Heart” by Randy Henderson is a Hansel and Gretel story. It does not differ so very much from the Grimm version; Hansel and Gretel are abandoned by their parents to the wood, and find a gingerbread house and a witch who calls herself Granny Bab. Henderson opens his tale after all that, once Hansel has been stuffed away in the stable and Gretel pressed into service.

Where this tale diverges is that the witch offers to take Gretel on as an apprentice. It’s not a hard sell, considering the witch treats her better than anyone else in Gretel’s short history. But the story ends just as the Grimm version ended, and how Gretel acts at that moment is the real story here.

Henderson’s version is a study in nuance. Even Hansel, whose blood appears more in the story than he does, is still made complex through the layers of interpretation provided by Gretel and the witch. “A Witch’s Heart” is like that; the larger world the story hints at feels every bit as complex and haunting as the kindnesses of Granny Bab.

“The Sacrifice” is a medieval fantasy about a princess and a law clerk, or a dead woman and a wise man, or a warrior and a mage. Written by Michelle M. Welch, it tells the story of what happens when a princess gives up her most precious commodity to save her father. It is not a nice story.

It is told mostly from the perspective of Gilien, a clerk apprenticing with the judges of a village in the south of the kingdom. He and another apprentice, Anders, are sent to investigate an old woman’s story about a beaten and comatose girl who her nephew dragged into her house at night. The girl’s state is something of a shock for Gilien, and she is as pathetic and vulnerable a figure as you can imagine. Later, she single-handedly kills a half-dozen mercenaries, turning the tide of an attack on Gilien’s village.

Welch’s narrator has a striking voice. She is quite good at finding the fewest possible words to relay an image; the verbal equivalent of gesture drawings, where three swift lines become a crane in flight. The craft of the narration combined with the pathos of the plot make this story into something sublime.

“Little Vampires” by Lisa Goldstein has four stories in it, the outer one, the middle one, and two inner stories that reflect each other in exactly the way vampires and mirrors don’t. It’s a slow horror piece. The outer shell is an old woman answering her daughter’s request with a story. That story, the old woman’s memories, is the middle layer. And what she remembers is two women telling her stories over drinks one night. One is a story about vampires. The other is a story about camps, and what happens to those who survive. Goldstein uses these nested stories to build the sensation of being disturbed. Each layer is an even weightier tale, until even the narrator’s simple act of answering her daughter’s question has grown fat with implications. It is an okay story to read at night, though not, perhaps, a story to read at family reunions.

“By Shackle and Lash,” by Euan Harvey, tells the story of a mysterious prisoner with blue eyes like the warm harvest days of summer. Kemal and Wahid are men of the Mukhabarat, a sort of police organization that serves the Shah, but they abandon their duties and are sentenced to work in the dungeons. It is here that they come across the woman in cell Alef seven. She is weak and sick and has recently soiled herself, but she has her eyes and a mouth that tells the men things they cannot remember and cannot disobey. I am unfamiliar with folk traditions from the Middle East, so it very possible I am missing references; I do know, however, that the story stands on its own. It has a hypnotic quality that should not be denied.

“The Strange Case of Madeleine H. Marsh (Aged 14 ½)” by Von Carr is a delightful Buffy-meets-Eldritch-horrors piece. Its playful tone provides a lovely counterpoint to the darkness and pathos of the rest of this issue. It is also an interesting modern interpretation of Lovecraft’s work. Often the focus of Lovecraft’s work was the reaction his protagonists had to the unspeakable wrongness of the universe. However, the protagonist, Maddie, watches reality TV, and is thus well-versed in unspeakable wrongness. Her little adventure was the perfect end to this issue.