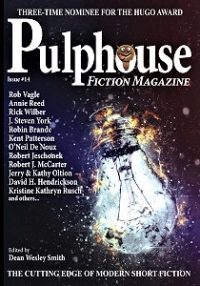

Pulphouse #14, October/November 2021

Pulphouse #14, October/November 2021

“The Soul Mate Junkie and the Beating Heart” by David H. Hendrickson

“Ecstatically Ever After” by Jerry and Kathy Oltion

“The Bridge” by Robin Brande

“Lower than Black” by O’Neil De Noux (reprint, not reviewed)

“One Sun, No Waiting” by Annie Reed (reprint, not reviewed)

“Lifetime Value” by B.A. Paul (non-genre, not reviewed)

“Roadkill” by Brenda Carre

“Living Free” by Dory Crowe

“Ice in D Minor” by Anthea Sharp (reprint, not reviewed)

“Harry the Ghost Pirate” by Robert J. McCarter (reprint, not reviewed)

“The Cactus, the Coyote, and the Lost Planet Joyride” by J. Steven York (reprint, not reviewed)

“Lucky Charm” by Alexandria Blaelock

“Romeo Peterbilt and Isuzu Juliet” by Kent Patterson

“Mounting the Monkeys” by Rick Wilber (reprint, not reviewed)

“Amelia Pillar’s Etiquette for the Space Traveler” by Kristine Kathryn Rusch (reprint, not reviewed)

“Predict THIS” by Michael D. Britton (reprint, not reviewed)

“Family History” by R.W. Wallace

“Time in Death” by C.A. Rowland

“Where Everything Goes” by Rob Vagle

“The Men Without Heads Join a Health Club” by Robert Jeschonek (reprint, not reviewed)

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

With the exception of a single crime story, all the original works in this issue are science fiction or fantasy.

The protagonist of “The Soul Mate Junkie and the Beating Heart” by David H. Hendrickson works in a factory that transforms her emotions into products designed to help people find and stay with their true loves. Worried that her relationship with her boyfriend is going sour, she attempts to steal some of the pure emotion taken from the other employees for her own use.

The premise is interesting, if rather implausible. The believability factor is reduced even more at the story’s climax, which involves the inanimate coming to life. If one can get accept this, the tale offers a lesson in loving not wisely but too well.

In “Ecstatically Ever After” by Jerry and Kathy Oltion, an old married couple have their consciousnesses downloaded into a computer simulation after they die. This seems like paradise for a while, as they enjoy their young, perfect bodies in virtual versions of fabulous locations. After a while, their sex life become routine, so they seek ways to improve it.

This is a very light story, best read as a mildly risqué joke. There is not much more to it than the basic plot, which may be worth a few chuckles.

The title of “The Bridge” by Robin Brande has at least three meanings in the story. There is the snow bridge through which the narrator’s husband falls, leading to his death; there is the ability of the narrator’s friend to channel the spirits of the deceased; and there is the metaphor of accepting a new life after loss. The friend is dying from a terminal disease, leaving her very weak and fragile, but she agrees to allow the narrator to communicate with her husband one last time.

The plot is very simple, and the fate of the narrator and her friend is predictable. The author conveys the character’s emotions vividly, and makes it clear that one must go on after bereavement.

In “Roadkill” by Brenda Carre, a young girl who is bullied by her schoolmates has the ability to bring animals killed by automobiles back to life. The narrator is the girl’s only friend, and the story’s climax reveals her true nature.

You can probably guess the narrator’s secret just from this brief synopsis. It is also not very surprising that the girl gets revenge on the bullies. Although predictable, this grim tale manages to be a chilling horror story.

“Living Free” by Dory Crowe features sea dragons (marine animals similar to seahorses) who are imprisoned in an aquarium. They are able to communicate with an autistic boy, who figures out a way to set them free.

The author does a fine job of writing from the point of view of nonhuman creatures. The story is a heartwarming one, if sentimental, and is best suited for younger readers.

The title of “Lucky Charm” by Alexandria Blaelock refers to a boy’s baby sister. When they are together, everything works out well; when separated, tragedy follows, even the deaths of their parents. When the boy grows into an adult, he becomes his sister’s guardian. Inevitably, they grow apart when he marries, leading to disaster.

The concept is intriguing, and is subtle enough to be believable throughout most of the story. The apocalyptic event at the end is less plausible.

“Romeo Peterbilt and Isuzu Juliet” by Kent Patterson takes place in a future of fully sentient trucks. A driver owes money to a loan shark. Meanwhile, his truck wants to put on a musical with an all-truck cast. This proves to be a great success, but the driver is still in danger.

Despite some threatened violence, this is mostly a silly comedy. The songs in the truck musical have punning titles that may elicit groans. People who are interested in trucking and/or musicals may be more amused than others.

“Family History” by R.W. Wallace is one of a series of tales about a pair of ghosts who are not yet able to leave the cemetery holding their bodies. While waiting, they help other ghosts move on to the next world, by uncovering murders or completing other unfinished business.

In this story, a ghost is released from a century of confinement in his coffin when workers dig up his grave, because his family no longer pays for its lease. Aiding him in escaping existence as a ghost involves a scandal dating back to the First World War.

The ghosts are fully developed characters, as are the living people in the story. The plot is clever and involving, and the sense of time and place is richly conveyed.

In “Time in Death” by C.A. Rowland, a condemned murderer is allowed a little more comfort than an ordinary prison cell by serving as a time-traveling investigator. His current assignment causes him to jump back and forth in time, as he tries to find out what really happened in a murder to which the supposed killer already confessed.

The plot moves very quickly, so some readers may not take the time to ponder the implausibility of asking killers to act as detectives. As in many time travel stories, the logic of the premise is questionable. Although the protagonist can interact with people in the past, there seems to be no effort to prevent the murder from happening in the first place.

“Where Everything Goes” by Rob Vagle is a madcap comedy about a man who winds up in a dryer, where he finds all the things that disappear, as well as a strange little being who tells him what he must do to escape. This goofy little bagatelle may raise a smile, even though its lack of any real change at the end makes it a shaggy dog story.

Victoria Silverwolf ate some vegan “shrimp” recently; it was unnervingly realistic.