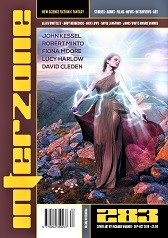

Interzone #283, September/October 2019

Interzone #283, September/October 2019

“The Winds and Persecutions of the Sky” by Robert Minto

“Jolene” by Fiona Moore

by Mike Wyant Jr.

“The Winds and Persecutions of the Sky” by Robert Minto takes place in a world where humans have locked themselves away in the decaying remnants of skyscrapers to defend against some sort of ancient chemical warfare. It’s set far enough past the original cause the main character, Sib, doesn’t seem to have any point of reference for his people’s obsession with cleanliness and isolation. The story itself is about Sib leaving the safety of his home to look for his friend, Malmo, whom he is convinced has been abducted by the flying humans outside the walls. To get to Malmo, he makes a deal with Trader, a young woman from outside and takes to the walls.

Overall, I really enjoyed the imagery and the depth of world-building throughout. However, there were a few things that caught my attention a little too much and broke my suspension of disbelief. The first one comes early, but only becomes an issue later. That issue is Trader herself. She’s one of the outsiders, which is made very clear early on, but Sib, the same Sib who only just broke the rules to leave his floor, let alone the building, knows her and somehow barters with her to help him find his friend. That presents a plot hole I couldn’t let go of despite my best efforts.

The second thing was in the ending. Through flashbacks, we see Sib as Malmo’s fawning toady, an assistant who constantly changes himself and his desires to meet whatever Malmo’s current obsession is. With the ending, I expected this to change, to see growth in Sib that showed his motivations were no longer dominated only by Malmo’s passions. I won’t spoil the ending, but suffice to say, I didn’t see the growth I was looking for.

In short, a nicely written story with great world-building, but the plot and character growth didn’t quite land for me.

“Of the Green Spires” by Lucy Harlow is more poetry than prose. It’s a story about a strange plant called starthistle that grows all kinds of fruits, takes over a city, then retreats to create its own replica of portions of that city in the countryside. The (sub)plot has to do with a woman named Katherine who is having deep issues with her sister, only to have them solved, somehow, with the help of the starthistle and its fruits.

As I mentioned, this is a poetic work and Harlow is definitely a poet. I read many of the lines repeatedly just to enjoy their cadence and form. At the very least, it’s worth reading to feel what successful poetic prose can do.

That said, I didn’t have the same reaction to the plot. When I reached the end, I sat back and said, out loud, “Is it really just a story about a plant helping fix a family?” If it is, then I didn’t feel the intensity and importance of it throughout. This may be a reach, but I think the beauty of the language actually detracted from the impact of the plot, because when you’re reading about something so beautiful and miraculous, of course the relationship in question will be salvaged.

In the end, I didn’t like the story, but I really enjoyed reading it. I think you’ll need to give it a look and make your own decision on this one.

Fiona Moore‘s “Jolene” is funny in a twisted country song sort of way. The story follows Noah, a Consultant Autologist, which is like a psychologist for Intelligent Things (capital I and T), but a specialty in intelligent automobiles. The opening hook is in itself a joke: there’s a country singer whose wife, dog, and truck have all left him; the dog is dead, probably can’t do anything about the wife, but maybe the truck thing can be resolved. From this point, Noah speaks with the country singer in question, finds out his former partner on the National Competition circuit, a ruby red pickup named Jolene, has left him to work in a quarry, and won’t speak to him anymore. Yes, there’s a Dolly Parton joke. Yes, it’s funny.

Then the story takes a really dark turn about halfway in. We find out the dog got killed by Jolene, the wife is burnt alive, etc., yet the humorous tone doesn’t waver. By the time the story ends, I was confused by the transition and actually double-checked to make sure I didn’t somehow skip a few pages.

Overall, it’s funny, but the darkness at the end overwhelms it all.

“The Palimpsest Trigger” by David Cleden is dark. Really dark. It follows Marni, a drug addict who caused his sister’s overdose years before, as he works as a makeshift assassin for these monstrous creatures called palimps that can rewrite human memories. The palimps, in addition to rewriting memories, can also implant something called a meme-bomb through the use of their pilla, a nasty cilia-like growth they can remove and send out to their targets. The meme-bomb plants a trigger in the target’s brain which, when the target sees a certain item or symbol, causes the person to die horribly.

The story itself is driven by Marni’s desire to remove his memory of his sister’s death as it’s slowly driving him mad. He does horrible things for a palimp named Socrates in pursuit of this goal until, one day, he takes a target unlike any other for the sheer chance he’ll have his memory wiped.

The story kind of grossed me out and the ending wasn’t much of a surprise (I took pains not to mention it here so as not to ruin it for other readers). Even remembering the descriptions of the palimps makes my stomach turn, especially the weird blowjob scene with the house Madame and the palimp. Yes, it’s real. No, it’s not sexy.

If you’re going to read this, go in knowing that Cleden can write some nasty descriptions in ways that’ll haunt you for days.

“Fix That House!” by John Kessel is a farce targeting “authentic” home remodeling shows. The story follows an unnamed narrator and his spouse as they invest in an old plantation house and proceed to convert it back to its original form, down to the original, unusable kitchen. The story really gets to its punchline after they buy their first slave, Dottie, then drops off to make its point when the narrator sits on the front porch of their home at sunset with plans to go “go out and visit her later.”

This is a dark humor piece that, I think, highlights the ability of mostly white folks to look fondly on problematic time periods without seeing any of the ugliness beneath it. Personally, I think Kessel is saying he thinks these folks are yearning for those days not because they find a missing grace, but because they’re secretly wishing for the utter control they had and the freedom to do whatever they want as long as it’s done to people of color, but I could be wrong. Maybe.

Mike Wyant, Jr. is an ex-IT guy, who has finally committed to a writing life out in the Middle of Nowhere, New York.