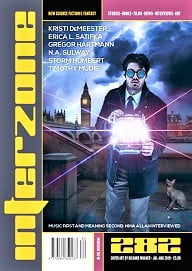

Interzone #282, July/August 2019

Interzone #282, July/August 2019

“Verum” by Storm Humbert

Reviewed by Tara Grímravn

“Verum” by Storm Humbert

Rev is a reality mixer—something of a mix between a drug dealer and an artist. Several years back, he invented verum, a drug that lets you briefly experience life as another person, and his bank account swelled as his client list grew. In recent years, though, others have taken up the trade and Rev’s no longer the only mixer in town. One, in particular, poses the biggest threat to his empire, forcing him to find a way to compete with the brilliant dreams that her verum creates.

One glance at the above summary and one might get the impression that Humbert’s story is an action-packed encounter between two warring criminal factions. In reality, though, “Verum” is a bittersweet tale about friendship and the human condition. The narrative’s feel is somber and, as a result, it was a little slower-paced than expected but still a very good read.

“Can You Tell Me How to Get to Apocalypse?” by Erica L. Satifka

A few years after a virus has ravaged women’s reproductive systems, talent wrangler Annette works for a children’s show called Gumdrop Road. As one might expect, the stars of the show are a group of kids. But there’s something different about these young actors—they’re all dead. Even so, they play a vital role in society.

Satifka’s story is a nice blend of horror and science-fiction and, given the mention of dead children above, one might think that this is another zombie apocalypse-style tale. In reality, though, it’s something else altogether. There are no scares, no flesh-eating abominations, or anything else of the sort. The horror here is psychological, stemming from the hopeless and irreversible situation in which the entirety of the human race finds itself. Unable to procreate, humans face an inevitable extinction within a single generation. Everyone knows that when those currently living die, it’s “lights out” for the human race—there will be no children to carry on their legacy or continue their bloodlines. It’s also delightfully ghoulish (and incredibly inventive on Satifka’s part) that the kids are electronically-controlled corpses that are repeatedly frozen and thawed until their flesh finally gives out and they have to be reburied.

“The Frog’s Prince; or, Iron Henry” by N.A. Sulway

Sixty years ago, Henry was just a frog, lured from the lake by a young boy wanting to be free of a family curse—a curse that says he’ll never have a “daughter born of a woman.” Tonight, Henry and his lover, now struck with a malady that affects his memory, sit in a restaurant they once owned together as the frog-now-man reminisces about their life together.

This was an interesting twist on the “Frog Prince,” a German fairy tale that should be familiar to most readers. The aspect of the story that I found most intriguing was what appeared to be a nod to the original, more violent, version of the tale. The “true love’s kiss” trope that shows up in later versions of “The Frog Prince” doesn’t play a role here. Instead, the relationship between Henry and his “prince” is a bit warped—so much so that I had to wonder why Henry wanted to stand by the prince after all this time, especially after being forced into so many magical transformations from a male into a female. But then again, one could ask the same of the original tale—why did the princess, who abused the frog before throwing him at a wall, get to marry the prince he finally became?

Which brings me to the next point of what exactly the story was intended to portray. I’m honestly not sure what the intention was. It started as a genuine tale of love between two people but, after reading further, I wouldn’t call the bond between Henry and his prince “love.” His lover uses him more as a means to an end (the begetting of daughters) while Henry’s affection for him, on the other hand, seems true and real. Honestly, I felt a bit sorry for Henry because he really seemed to get the raw end of the bargain here.

On a final note, the only issue I had was that I’d have liked a glimpse into the cultural reasoning why daughters were so important. The prince forces Henry through several transformations into a woman in order to have daughters but why the gender of the children was so important was never explained. That said, there may be some deeper meaning intended here that I am simply missing.

“The Princess of Solomon Pond Mall” by Timothy Mudie

Young Kaya lives alone in Solomon Pond Mall, barricaded in by the military that keeps her incarcerated here for the safety of others. Five months prior, Kaya made everyone in the mall disappear, not on purpose, but entirely on accident. She doesn’t even know how she did it. To protect her and others, the military delivers food and supplies via aerial drops in the mall parking lot. The last drop, however, contained a surprise—a small robot to keep her company. Frightened that she may make him disappear, too, Kaya tries not to let herself get too close to him but, eventually, she begins to accept him as a friend.

At first, I thought this might be another apocalypse-type story but it wasn’t. Instead, this science-fiction piece was more geared toward a little girl trying to cope with being left all alone due to some part of herself blinking people away without her intending to do so. But while the plot has the ring of an episode of Amazing Stories (1985-1987), it was bland. There is a lot of potential to explore Kaya as a character but that doesn’t really take shape. Nothing of any real importance happens to her and no real discoveries are made about herself. She’s just alone and bored. She doesn’t feel threatened by those keeping her there, even though we get a snippet of conversation showing that they may mean her harm. And the robot’s uncertainty about the nature of its own existence and whether it’s alive or why it can feel emotion was treated almost as an after-thought as if to deepen the meaning somehow but missing the mark instead. Overall, the story was underwhelming.

“Heaven Looks Down on the Tomb” by Gregor Hartmann

Mei is Collector #1, the lead in a group of unruly graduate students sent to Earth long after humans abandoned it to live on the moon, now called Luna. Their mission, led by Dr. Wong, is to eat and drink from terrestrial sources in search of new microbes to create new symbionts that could be used for various biological purposes. Unfortunately, dissenting political parties back on Luna want the mission shut down, declaring Dr. Wong and the students a danger to all human life as biological weapons. Upon being given the order to return to Luna immediately for quarantine and interrogation, Mei has to find a way to keep her and her subordinates from losing everything they’ve worked for.

One of the longer pieces in this issue of Interzone, Hartmann’s story was a very engrossing read. The overall story arc and Mei’s character arc were quite well-developed. It was very well-researched, too, and the small details that Hartmann included were appropriate and helped put me into that setting. After all, Mei and her companions might be human but no one’s lived on or visited Earth for three hundred years. They are essentially aliens at this point. Hartmann took the time to describe the effect of that Earth’s gravity might have on someone who’d been born and raised in a much different atmosphere and gravity. He also put a good amount of thought into the political geographies in which lunar colonies might organize themselves once all human life on Earth had been wiped out, as well as the cultures and behaviors that might arise in a society that is largely tech-based with no natural environment whatsoever. For me, that was very refreshing. This was a very good read indeed.

“FiGen: A Love Story” by Kristi DeMeester

After fifteen years of marriage, a college professor and her husband have begun to drift apart. One evening, she sees an advertisement for Fidelity Genetics, or FiGen, which claims to be able to determine with 99.9% accuracy if a spouse will cheat and with whom based on their DNA profile. Determined to find out if her husband has been, or would be, unfaithful she stealthily snips a lock of his hair and sends it in. When the results come, it isn’t exactly happy news. A few days later, the professor runs into her husband’s potential affair and things take an unexpected turn.

DeMeester’s story is heavily character-driven which, because it’s incredibly light on any science-fiction aspects, creates a single insurmountable problem. I’ll start by saying that focusing on why characters make the choices they do to drive the story forward isn’t a bad thing. Character-driven story arcs are well-loved by writers, readers, and critics alike, and for good reason. It allows the writer to develop the character and helps the reader to connect with them. The problem with “FiGen: A Love Story” is that it purports to be a science-fiction piece. Considering that it’s published in a speculative fiction publication, one would expect it to be just that. Upon reading it, however, it becomes clear that DeMeester’s story is actually a literary piece with only the vaguest, most subtle hint of SF possible added to make it qualify for inclusion in a genre magazine. It reads as if this story was initially written for a literary fiction publication, only to have the genre elements added later in an attempt to make it fit a different audience without having to rewrite the original too much.

Luckily, the story plays out at a decent enough pace. This was its one-and-only saving grace because otherwise the plot is just boring. Had it not been for the pacing bringing the story to a relatively swift and merciful conclusion, I would not have had enough interest to force myself to continue reading to the end.