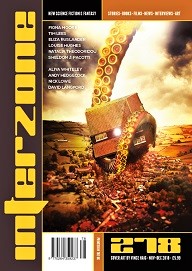

Interzone #278, November/December 2018

Interzone #278, November/December 2018

“Soldier’s Things” by Tim Lees

Reviewed by Gyanavani

The six stories published in this issue of the British magazine Interzone are of varying quality and caliber.

Tim Lees’ “Soldier’s Things” anticipates a prospective future in which a disabled and severely disturbed veteran is trying to integrate into civilian life. Before he signed up and was shipped off, the soldier, whose name we never find out, lived a wholesome existence with a loving family and a youthful sweetheart.

Once he is discharged he journeys back to his hometown to meet his single living relative, his brother. In his travels he understands a few bitter truths—not even a faint breath of the grim reality of war touches the city even though that very same war has showered riches on it; the war’s propaganda machine fills the minds of young men with an idealistic sense of duty and a code of honorable conduct; and lastly that the soldiers at the front are reprogrammed by surgical implants that flood their minds with false and corny images of a loving family, helpless new born infants, a childhood sweetheart—images that help them stand against the horrific creations of the enemy.

It is a truth well documented through the ages that war is a necessity for the rich and the powerful as it makes them richer and more powerful. The flip side of the coin is also well-known as records exist of the pain and suffering of ordinary folk in battle. Yet, puzzlingly, when wars happen the common folk sign up willingly. Tim Lees in this brilliant story has built a simple but profound explanation of how soldiers have been made in the past and will continue to be made.

Fiona Moore’s “Doomed Youth” deals with a young woman, Kara Chong, a graduate student at the university, who answers an ad for a housemate in a quiet and respectable neighborhood. We soon learn that the western world of the near future in which Kara resides is struggling to protect itself from the influences of foreign cultures. Kara herself is an American of Asian descent and the snippets of information about her past that we receive in flashback show that she has suffered intensely from racist attacks.

In the neighborhood there resides an old woman who has suffered from a tragic loss when she was young. It has made her unpredictable and hostile but the long term residents of that neighborhood protect her. By the end of the story Kara Chong is under arrest for starting a fire only because she has a flame thrower in her hands, while the old lady remains invisible to everyone even though she too has a flame thrower.

There is some mention about ants that have suddenly grown to gigantic proportions but in the final analysis they don’t count for much. Our heroine spends some time researching the reason for this growth spurt among ants and she discovers nothing.

This story does not belong to a magazine dealing with speculative fiction. Just because Fiona Moore mentions something about overgrown ants does not make it science fiction. In the larger scheme of this story it is just some detail added to give texture to the world created. The writer could easily have dropped the ants from the story and it would make no difference.

Louise Hughes’ “Path to War” is a stylish recital about a story teller who prides himself on telling unique tales. Unfortunately, his off beat style does not win him many admirers and his prickly personality does not gain him friends. When war comes to the land he is currently residing in, he decides to go back to his own country. On the return journey, events transpire that will give him the ring side seat to the enemy’s attack on the mountain passes.

This spirited story boasts a central character that is entertaining in its single-minded devotion to creating his poetry. An important question that the author does not answer is the quality of our protagonist’s creations—knowledge of which would heighten the vein of dark comedy that runs through this narrative.

In Eliza Ruslander’s “Heart of an Awl” a widow transplants her dead husband’s body and organs onto his car. The entire story deals with the car’s understanding of its new self and the blossoming of a romantic relationship between the widow and, for want of a better word, her husband’s car.

This story is problematic for many reasons. 1) Nowhere in the story is there any mention of the wife’s undying love for her dead spouse. At one point the car/husband realizes that he and the wife were but possessions of the dead man. Why did the widow want to keep her husband alive? 2) Why did she decide to animate the car? 3) If the decision was made in anger to reduce the dead husband’s significance then why does she feel obligated to be understanding towards this new creation? 4) Why should the car and the widow’s decision to live like motors be so revolutionary that the car expects a sizable number to follow? 5) Lastly how can a fossil fuel guzzling man-made machine understand the significance of our denuded forests and plan to rebuild them?

“Zero Day” by Sheldon J. Pacotti tells the story of a cyber operator in the US Air Force who finds the girl of his dreams on the day he decides to take unsanctioned leave. After he loses sight of her he spends the entire afternoon and evening in an increasingly desperate search for her. As this first person account progresses we learn that this was the day when, finally, war reached the “heartland” as the hero terms his country, the US.

The hero has taken this unsanctioned leave because he wants to hook up with a member of the opposite sex, a basic, simple need. The twist here is the hero himself whose expertise in virtual networks keeps him constantly aware of the virtual blocks that lead to traffic congestion or enemy hackers leading to airplane disasters but leaves him clueless about human emotions. He sees one beautiful blonde, spends a couple of hours with her, feels a deep connection with her and decides she is the one. His method for winning her hand is to set up a tracker on his mobile and later when he is close to her to hack into her social media profile. Even when he has the chance to go up to her and chat with her, he chooses to send her a long text message.

This is an important story because given that our soldier cannot separate the virtual from the real can he, even though his actions greatly helped the war effort, truly be considered a hero? From the throw away remarks in the story we have to gather that the war is won at great cost of personal freedom.

“Birnam Platoon” by Natalia Theodoridou deals with enhanced plant-based soldiers who cut the cost of military operations in half (they photosynthesized their food) and also significantly reduced casualties and losses. These soldiers were also a pleasure to command since they never questioned orders and were almost always successful in completing their mission.

But these soldiers had been told their purpose was to end war, suffering, and pain. After three years of inflicting untold violence on different people they collectively decide to give up arms. Their peaceful uprising has violent results. Their grieving handlers line these non-human soldiers and summarily execute them.

The story is told by one of the handlers, Marion Romfell. The war is lost and she is incarcerated in a military prison where she is being tried by an international military tribunal for wartime atrocities. The author gives Marion two voices, one the official statement recorded by the tribunal, and the other an informal telling of the events to a young stranger who begs for it.

The writer, Natalia Theodoridou, of this beautiful story is technically adept and commanding. Yet I still hesitate to call it a gem of a story. I think the reason for that is the writer has not distanced herself from her protagonist’s cynical world view. Her super beings are novel and exciting but their sentiments are imprisoned in a human narrative that is both crude and vulgar.