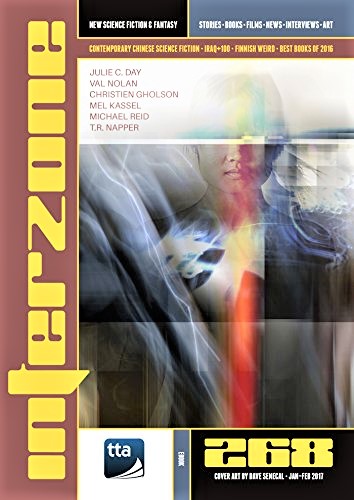

Interzone #268, January/February 2017

Interzone #268, January/February 2017

“Everyone Gets A Happy Ending” by Julie C. Day

Reviewed by Jason McGregor

This issue of Britain’s Interzone presents us with six fairly short stories (four SF) which mostly deal with revolution and apocalypse and mostly would seem to involve Asia (usually China) and/or the US either directly or symbolically. Only one stuck out as particularly good but only one or two stuck out the other way, so it’s not a bad issue overall if it’s your kind of thing.

“Everyone Gets A Happy Ending” by Julie C. Day

Once again, it’s the end of the world. In this fantasy, the method is via humans becoming immaculately pregnant and producing bunnies instead of more humans. Steph (the pregnant one) and Kendra leave an Ohio that is inhospitable to bunny-carriers and head out to Sister Francis’s New World Sanctuary in Arizona. The rest of the story deals with how the two (and Sister Francis) deal with the situation and each other.

This story mentions mosquitoes once in passing and it does seem to be Zika-inspired. But I’m very tired of “end of the world” scenarios which seem to be enjoying a resurgence in all media lately, even when they unusually choose bunnies (though not as unusually as, say, the Sta-Puft Marshmallow Man—which, incidentally, was an apocalypse averted). Still, it’s decently, if sketchily, characterized and, while there’s little action to take up much space, it’s pretty concisely told. It may have its fans.

“The Noise & The Silence” by Christien Gholson

Trying desperately to avoid narrative, the two threads of this story, dealing with Reen and Aliss in snippet after snippet, nevertheless almost tell a story about an old revolutionary who has spent a decade in jail and the two decades since in a jail partly of his own making (Reen) and a one-time anti-revolutionary who was won over to the cause (Aliss). The woman has never really lost her fervor and helps the man regain his. The setting is a vaguely futuristic dystopia that isn’t Earth (wink, wink) and “the noise” is the force of advertising and government and business and self-deception and basically the Tick Tock Man while “the silence” is the inner Zen tranquility and listening to others and Amishness and all that.

“One thing that never changes—the avant-garde.” This reads vaguely like PKD if he’d come along in the 60s rather than the 50s which is of dubious merit at any point but not exactly something to aspire to in 2017. Its concerns are quite topical for 2017 but also aren’t anything the 50s didn’t feel. Either way, it was entirely too long (just shy of a novelette) and quite a slog to read. Must be art.

“The Transmuted Child” by Michael Reid

Sister Dao Nghiem, a Vietnamese Buddhist, and Esmonde Okoh, a child with defective alien implants which are driving her insane, travel to meet with the Erkess Senate to explain their problem and seek redress. Given that the Erkess are entities whose primary sense seems to be smell and who speak musically and whose brains, stomachs, lungs, and whatnot are interchangeable and somewhat self-sufficient, and given that they are primarily just in a bidding war with another alien race, the Urtet, to acquire influence over humanity, it is hard to make them understand the problem. Despite Esmonde, in her lucid moments, being the ostensible translator, it is Dao who is required to go to extraordinary lengths to get the message across.

I find the worldview, with its passivity and other things I can’t get into without implied spoilers, to be extremely uncongenial and don’t personally care for the story for that reason (and I can’t help but think the Erkess and Urtet are intended to be the US and China (or vice versa) and Viet Nam the Third World, generally), but it’s not to the point, as there’s not much else wrong with it. It is a well-crafted and effective story with an interestingly exemplified title and is genuinely (a loose sort of) science fiction. Any story that initially confuses the reader with lines like, “A flock of Erkess lungs flutter past, attracted by the updraft,” but comes to make sense and tell an actual story is doing something right.

“Weavers In The Cellar” by Mel Kassel

A slow short-short (not exactly “flash”) fantasy about a new order in the talking bug world in which the spiders are subservient to ants and flies and such.

“Freedom Of Navigation” by Val Nolan

After the shortest story in the issue, we get the longest (the issue’s only novelette, though a short one). A cybernetic pilot of Mars, amidst his ship and AI-like drones—all of which constitute a “centaur”—is taking part in a Freedom of Navigation operation over a space rock the Belt Republic has repositioned and laid claim to. Fighting erupts, the human component of the centaur is stranded on the rock, and there follows a fight for survival in which remnants of his own drones mistakenly believe he’s defected and attempt to neutralize him.

While the action sections of the narrative are active and the infodump sections have their interest, this story is still too clearly built of these two blocks, each of which are somewhat faulty. The opening section comes across as unmotivated and the infodump sections, set slightly back in the main action’s timeline, eliminate most narrative thrust. Also, while FONOPs can apply to any entity doing something questionable and any other entity with the resources to contest that, this has the feel of being another timely Chinese/US story, in which the asteroid belt is the South China Sea. All that said, this story does something clever with the first-person narrative and it’s hard to go completely wrong with a cyborg space combat story, so I didn’t mind it and can imagine it having its fans.

“The Rhyme Of Grievance” by T. R. Napper

In a world which has created an AI in the form of a female robot, a revolutionary group has formed in order to try to eliminate it and the three scientists who created it. They recruit Khamla, a low-caste Asian girl whose fatal disease they cured, to act as the central component in a coordinated attack plan. Khamla’s job is to kill the AI while attacks against the scientists are occurring elsewhere. The climax involves her confronting that AI in a talky “will-she/won’t-she pull the trigger” scene. Interspersed with the main narrative are flashbacks which get out the “fraction of a fraction of a percent who control everything and the AIs that will control them must be stopped” philosophy.

This handles its basically identical narrative structure better than the previous story except that the infodump sections, while extremely pertinent, aren’t especially enthralling and the action is mostly… not. But at least we’re given the motivations at the right times and the blocks are more smoothly integrated with the info having at least some “action” and the “action” having quite a bit of info. Still, nothing new here or executed extraordinarily well. Adequate.

More of Jason McGregor‘s reviews can be found on his Featured Futures blog.