“Johnny and Emmie-Lou Get Married” by Kim Lakin-Smith

“Johnny and Emmie-Lou Get Married” by Kim Lakin-Smith

“Unexpected Outcomes” by Tim Pratt

“Lady of the White-Spired City” by Sarah L. Edwards

“Microcosmos” by Nina Allan

“Ys” by Aliette de Bodard

“Mother of Champions” by Sean McMullen

Reviewed by Jeff Spock

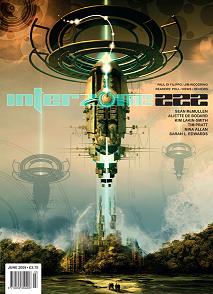

This issue of Interzone was a fine example of a very good magazine. The stories ran the gamut from good to great, with standout efforts by Kim Lakin-Smith, Nina Allan, and Aliette de Bodard. The content ranged across stories set in the world as we know it today, the world as it may be a few years from now, and worlds that do not exist.

Kim Lakin-Smith‘s “Johnny and Emmie-Lou Get Married” was a particularly interesting story for me. It is unquestionably a cyberpunk style story, yet placed in a retro 1950s setting. Though the protagonists were named Johnny and Emmie-Lou, the content of the story was anything but innocent sock hops and drive-in movies. The story is brief and efficient, taking place before, during and after a near apocalyptic drag race. Johnny and Emmie-Lou want to get married, but there is the problem of rival gangs, ex-suitors, and physically getting to a church located on someone else’s turf.

The language, like the story, is hard, as if William Gibson had written American Graffiti and it was put on screen by Quentin Tarantino. “The engine had been cranked proud of the bonnets like a sprawling heart of chrome.” “Blades flicked out from palms and pockets. Time bled away. I was breathing stolen air.”

What makes the story even more interesting is that the setting is infused with the technical background of steampunk. Imagine the hot rodders of that era, using steam powered hydraulics and jet packs to soup up their hot rods. It makes for a uniquely hard and unforgiving setting which adds a nice slice of speculative grounding to a story that otherwise might have been written by S.E. Hinton.

While the wrap up was ultimately unsurprising, the style and the setting made for an enjoyable read and a nice opening tale for this issue.

Tim Pratt is upending our minds and our notions of reality again, but that seems to be what he enjoys. “Unexpected Outcomes” revolves around a classic and, dare I say, grossly overused speculative fiction trope: our reality is merely a simulation and an experiment by higher order beings.

However, in the hands of a competent writer even the sort of idea that has been used by everyone from Douglas Adams to the Wachowski Brothers can gain new life. Pratt supposes that not merely is our world part of a simulation, but that the people running the simulation have decided that it is over. Everyone in the world is visited by some form of a learned looking elderly man who explains that, from this point on, there will be no need to eat, sleep, or worry about diseases. No more pregnancies or births and no more deaths, except by accident or one’s own hand.

This of course is where it gets fun. What is the worldwide reaction to this? What happens over a period of weeks and months as humanity starts to adapt to these conditions? Pratt’s protagonist–also named Tim–decides to return to what is more or less home, where he meets up with an old friend, Dawson. Self-taught, inquisitive, and energetic, Dawson has come to a series of understandings and conclusions that suddenly take the story in a very different direction. Together, the two friends make a number of startling discoveries, and we end up in an unusual version of human freedom fighters versus the aliens.

Though it is a bit of a one trick pony, the story is enjoyable and unfolds in an engaging manner. It is a quick and easy read, and well worth the time.

The most compelling element of Sarah L. Edwards‘s “Lady of the White-Spired City” was the setting. The world, the villages, and the places into which the protagonist enters had an immediacy for me that gave the story a great deal of richness.

The tale follows an intergalactic high-ranking bureaucrat, Evriel, who returns to visit a planet where she once had an assigment–and fell in love. Due to differences in time and distance, she has come at late middle age to visit a town and a people who have grown many decades older than she has. Evriel travels there not only for professional reasons, but also to confront and defeat some very personal demons from her past. Edwards’s writing includes nice little touches of authenticity in both description and dialogue, giving a strong sense of place and character.

The plot grows deeper when the protagonist discovers that there is an ancient ballad written about her and the unexpected manner in which she parted from the planet. As we learn more of the ways of life and the histories of the mountain villages she is visiting, we also learn more about her personal tragedy and her attempts to come to terms with it.

Ultimately, the story was more interesting than it was enjoyable. I did not share the catharsis of the main character, nor did I entirely accept the ways that the different personalities within the tale affected each other. Looking back at the story, I remember it as a rich experience in a second world setting, though lacking the solidity of an emotional journey that would have elevated the experience from good to great.

Nina Allan‘s “Microcosmos” is a little gem of a story, a brief yet entirely believable and memorable tale. Resonant characters, perfect descriptions of its setting, and faultless intertwining of the present and the back story left this one echoing in my mind long after I read it.

Other than the indications of want due to high temperatures and a lack of potable water, this could have passed for a short story from a literary magazine. The science fictional elements in the setting (a near future somewhere in the American Midwest) add depth and color, but are hardly necessary to the progression of the tale.

It unfolds through the eyes of Melodie, a young girl who is off to visit a mysterious man –and uncle–named Ballantine. As the plot progresses, Allan shows us very elegantly through Melodie’s eyes a story of family secrets, recriminations, and loss. It is a very difficult thing to show a story through the eyes of a protagonist who does not understand everything that is going on, and the author has done an excellent job of this. We are pulled into the story by Melodie’s innocence, and it is framed in such a way that much of what we understand in the conversation between the adults, she does not.

Allan uses excellent descriptions of detail and moment to anchor us in her narrative. The details of the rooms, the car, the weather, and the characters’ clothing are rendered to add life and credibility to the story. A tube of sunblock that “smelled rank and

sulphurous, like the oil in a can of pilchards.” In a poor and stuffy house, “She was aware of an absence of dust.” I enjoyed hearing the tiny voice of the narrator whispering to me the thoughts and reactions of Melodie; like her and Ballantine I felt like I shared a secret confidence with the protagonist.

I recommend this one, and look forward to seeing what else Allan produces.

I should admit, before I continue this review of Aliette de Bodard‘s “Ys,” that in my opinion she writes some of the best fantasy currently out there in the market, always establishing a flawless sense of place and time. With this particular story I felt like I was in an armchair on the beaches of Brittany, watching as her protagonists went through their trials. Details like the smell of brine and wet ivy in present day Quimper, or the sound of the lost undersea city of Ys that hums with “a rhythm that is the roar of the waves and the voice of the storm–and also a lament for all the lives lost to the ocean.”

The story follows the unlikely quest of a young woman, Françoise, who has been divinely impregnated by the last remaining princess, Ahez, of the fabled lost city of Ys. Her partner leaves her due to the pregnancy and she is left alone, trying to deal with the nightmarish situation. She would be prepared to bring the baby to term were it not for a fatal flaw in its heart; as the story develops we see that the flaw in the child’s heart is mirrored in flaws and weaknesses in the lost city. However, the will of the demigoddess Ahez is bent on forcing Françoise to deliver the baby to her, whether she wishes to or not. Françoise is forced to make a series of difficult decisions, fearing the power of the goddess over her and her unborn child. She makes her own plans with an old friend, Father Gaëtan, who is also a collector of folk tales and legends.

The lives of Françoise and Gaëtan, like the lives of the city and the baby, come together in a final confrontation in the throne room of that drowned city-state. Poignant yet violent, the resolution of the story is powerful and ties together the threads of the narrative elegantly. De Bodard creates here a story that is credible for its everyday setting, and fantastic in its ability to transport us to another reality.

Okay. Enough superlatives. But, like I said, I like her writing.

Sean McMullen‘s “Mother of Champions” had me going back and forth. It’s one of those science-fictional works that has a background in some very interesting science, extrapolated by a wild imagination into something just outside of reality. However, I felt that there were some narrative flaws that kept me from being whole-heartedly enthusiastic about it.

Apparently the DNA of all cheetahs alive today is so similar that they appear to be identical–all of the thousands of them out there. The basic trope is that the cheetahs of the world have almost identical DNA because they have driven out all of the imperfect members of the species. What is fun, and what the author does very well, is to extrapolate from this to the idea that the cheetahs are actually the dominant life form on earth, and the rest of us are being ignored by, or entertaining them.

Kudos to Mr. McMullen. He goes even further than this with interesting ideas; he invents an ecological foundation that uses DNA alteration to save wildlife, causing trouble as when “the bile from bears that’s used in traditional Chinese medicine, suddenly becomes toxic to humans.” And even more clever touches such as the cheetah protagonist of the story playing with her human victim, much as a house cat toys with a captured mouse.

Yet, for me, all of the wonderful elements of this story didn’t quite pull together into a credible whole. The knowledge of a supreme cheetah tracking other cheetahs and knowing when their DNA had been tampered with was one example. The one that bothered me most, and turned the story from what had been interesting speculative fiction into silly fantasy, was when the cheetahs indicate that the six billion or so domestic cats on the planet are acting as spies and information gatherers.

While the wealth of scientific ideas and the richness of the imagination of the author made for interesting reading, these plot elements were far-fetched enough that they pulled me out of the narrative. Your mileage, of course, may vary. My final opinion is that McMullen has convinced me to read more of his work, though this particular piece is not my favorite of this issue of Interzone.