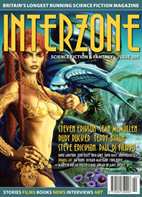

“The Measure of Eternity” by Sean McMullan

“In the River” by Justin Stanchfield

“2+2=5” by Rudy Rucker & Terry Bisson

“Blue Glass Pebbles” by Steven Mills

None of the above is a complaint.

“This Happens” is an explosion. An air force has dropped a bomb near a residence, and author David Mace rewinds the spool of time for us, showing in great detail what modern weaponry actually does. It is real horror told with great beauty, and if it stopped there it could have been one of the best anti-war pieces I’ve read.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t stop there. The author lets his anger get the best of him, and he lapses into lecture and finger wagging at the end. After you describe a small girl being ripped apart by a bomb, going on to say how this is a bad thing is unnecessary, and in a piece as well crafted as this, anything unnecessary weakens it. Still, even weakened, it’s still a powerful piece and worth the read.

Sean McMullan’s “The Measure of Eternity” is an interesting idea: a creation legend for symbolic mathematics. The King’s favorite concubine is aging, as people are wont to do, and, unfortunately, the King has decided that growing old is a capital offense for his concubines. In hopes of finding a way around the whole aging thing, the concubine sends her personal servant/slave to the market to consult with a beggar who is able to predict the price of silk with prophetic accuracy.

Unfortunately, this personal servant/slave, well . . . she’s a ninjette.

While having a female ninja (or a male one for that matter) as the main character of your creation legend for symbolic mathematics isn’t automatically a cosmic and unforgivable crime, having her give no indication of being said ninja until three-quarters of the way through the story whereupon she pulls out a belt full of throwing stars, straps it on, and then opens a can of vengeance-fueled whup-ass on the King’s elite guard is. It rips the plot into tiny shreds and turns a promising story into a cheap and hollow-feeling mess.

In Justin Stanchfield’s “In the River,” an alien starship has stopped at the edge of the Solar System. In order to communicate with them, a plan is devised: alien tissue is taken (how we got this tissue isn’t important) and implanted into a human brain, which will subsequently grow into a new sensory organ, which will allow that human to understand the aliens and figure out their math. That human is then to be dropped into the alien ship and, um, everyone crosses their fingers.

Given this problematic plan and some poorly developed relationship issues that crop up, I find myself puzzled as to why I liked “In the River.” I think it could be the Arthur C. Clarke vibe that spoke to the part of me which devoured Rendezvous with Rama. It may also be that the author set the story after the bad plan went awry, which keeps the plot problems from becoming quite so glaring. Whatever it is, it manages to turn a questionable plot into an enjoyable story, and I have to tip my hat to Mr. Stanchfield for that.

Issue 205 continues its math-based theme in “2+2=5” by Rudy Rucker and Terry Bisson. An overheard conversation in a coffee shop sets two men with a lot of time on their hands on a quest to break the world record in counting and to a discovery that there is something strange going on. The story is light, amusing, and sends the rational bit of my mind off to gibber in a dark corner for a while; I liked it.

Just as sand, rocks, and running water can, over time, turn a broken beer bottle into a semi-precious gemstone, the trials and tribulations we go through as people, nations, and a world will polish us into something more, something better. This is the metaphor in the title of Steven Mills’s “Blue Glass Pebbles.” It’s a nice thought: all the suffering we endure has a meaning and is good. Of course, it can also be used as an attempt to justify mass genocide, which, as thoughts go, is less nice.

“Blue Glass Pebbles” uses a war over water both as a warning for the future and a metaphor for the present in a way that is imaginative and timely, but, rather than focus on the action, the author decides to focus on a father, his daughter, and a family friend as they embark upon a cross-tundra trek to wrestle personal demons and become superheroes. This could have worked if I had bonded with the characters, but I found myself growing tired of their familial angst pretty quickly, placing this story in the “it-didn’t-work-for-me” pile.