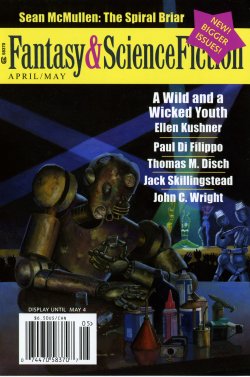

“The Spiral Briar” by Sean McMullen

“The Spiral Briar” by Sean McMullen

“A Wild And A Wicked Youth” by Ellen Kushner

“The Price Of Silence” by Deborah J. Ross

“One Bright Star To Guide Them” by John C. Wright

“The Avenger Of Love” by Jack Skillingstead

“Andreanna” by S. L. Gilbow

“Stratosphere” by Henry Garfield

Reviewed by Steve Fahnestalk

If there are any benefits to being away from the field for over a decade, the main one has to be the opportunity to read new and exciting works by new (to me) and exciting authors. F&SF has not disappointed me in that respect.

This issue has novelettes by new (to me) writers Sean McMullen, Deborah J. Ross and John C. Wright, as well as familiar and respected author Ellen Kushner; also short stories by Jack Skillingstead, S. L. Gilbow and Henry Garfield. (The reprints, Disch’s “Brave Little Toaster” and Edward Jesby’s “Sea Wrack,” won’t be reviewed here.) As one would expect from F&SF, the fiction is a good blend of both F & SF. (I’ve never been entirely comfortable with the term “speculative fiction,” as all fiction is some sort of speculation.)

Sean McMullen’s “The Spiral Briar” is a nicely delineated historical fantasy, involving the fifteenth century and, as Rod Serling used to put it, “the boundary between science and superstition.”

Because of what they did to his sister, Sir Gerald would be at war with the land of Faerie, if he could reach them, but the boundary between our world and theirs is too hard for mortals to cross, though elves, goblins and the like cross it at will to wreak their magic and mischief upon humankind.

He is approached by Tordral, a master armourer also harmed by the denizens of Faerie, who knows that the way to cross worlds is by use of the nascent science, involving the harnessing of steam. Steam can be used to propel boats and to throw heavy objects, like rocks or cannonballs, but to explore these uses will cost money, which Sir Gerald has but Tordral doesn’t. They have a common enemy in Faerie, and Tordral gathers around him others who have been twisted and would like revenge as assistants in his experiments. Their common symbol is a briar rose in a pot, for reasons explained in the story.

McMullen uses the familiar tropes of science and fantasy in an interesting meld; rather than using today’s scientific terms to explain the workings of Faerie, he uses what sound like authentic fifteenth-century terms in ways that would be consistent with both the science of the time and what in our world would be sheerest superstition but is nonetheless real in the story. And the people of the story act in ways consistent with the time as well. I found it enjoyable throughout.

Moving from full-fledged elf & goblin-type fantasy to what I might term semi-historical fantasy (there is no magic in the story that I could see), we come to Ellen Kushner’s novelette.

Although I’ve not read any of Ellen Kushner’s novels (though I have read some shorter fiction by her), her first novel, Swordspoint, provides both the impetus and the setting for “A Wild and a Wicked Youth”; and its protagonist, Richard St. Vier, is the subject of this piece. Rather than a full-fledged bildungsroman, it’s more of a transitional piece and a character study. Or to be more precise, three character studies: Richard, his mother, and the young noble he is friends with, Crispin (Lord Trevelyan-to-be).

The story details how Richard learned swordplay over a number of years from pre-adolescence to when he finally leaves home, and tells a lot in the process, of his home life and his relationship to Crispin, showing their relative social status and hints at the rest of the world they live in. (I would put it as late seventeeth or early eighteenth century.) As an aside, the story also details some of Richard’s sexual awakening, and it says something about our society that back in “the day” of Ed Ferman’s F&SF, parts of this might have been deemed too explicit for publication, though most of the sex in it is implied rather specifically.

Like all of Kushner’s fiction that I’ve read, it is well done, and leaves you wanting to know more, but as a story it suffers precisely because it is a short part of a larger world. I suppose I am damning this with faint praise, but it eventually left me unsatisfied because I needed to have read Swordspoint first. (Of course, now I *have* to go find a copy!)

Jumping from the alternate pasts to the unwritten future (one of the reasons I’ve always been enamoured of genre writing is the sweep of the timelines), we come to Deborah J. Ross’s “The Price of Silence.”

Well-done science fiction that is set in a future involving space travel used to require nothing more than steel hulls, some rockets, a semi-naval structure and some language like “clear jets!”; it was modernized somewhat in Star Trek (various incarnations) but still held to the archaic structure of the fifties under all the glitter of modern science. Then people started to think “what if societal structures changed as drastically as science did?” and you began to get different kinds of space-faring societies.

The spacefaring structure in this novelette is still somewhat similar to the old tropes; there is an Academy, some central government sends out colonists to Earthlike planets, and what is clearly a political officer of some kind is placed on board, but the crew of the ship Juno has a cross between a traditional spaceship structure and some kind of modern marriage/family in the Heinlein tradition; you lose your last name upon becoming a crew member (Devlin was not used to being merely “Devlin of Juno”) and everyone appears to have very fluid sexual and emotional relationships. Yet their shipboard roles are clear; Devlin is the Medical Officer, Shizuko is the Engineer, and so on.

That being said, the Juno is sent to find out why a ten-year agrarian colony on an Earthlike planet has fallen silent; the story details her voyage to the planet December and what they found there. The story was consistent; there was action, romance, loss and sorrow, and yet the ending seemed rushed to me. Overall, I liked this story pretty much, but like the Kushner, it could have (and maybe should have) been part of a larger work. But then, maybe that’s a fault of the novelette itself….

Now we come back to fantasy. I had never heard of John C. Wright, nor read any of his books, before reading this novelette. So I was not preconditioned one way or another, and had/have no axe to grind before reading. But frankly, I was disappointed in this piece; it appears to be an attempt to write an epic high-fantasy meets modern times story rather like C.S. Lewis’s Narnia series, but fails sadly in the attempt. I suppose one way to make a story fantasy is to throw in oodles and oodles of fantasy words and names, like “Tybalt” and “Myrddin” and “The Wild Hunt” and talk endlessly about haunted wells, and magic swords and recite made-up rhymes like “Unlock, unbind, release, set free; so says he who bears the key” and stuff like that there. But the whole thing reads like a bad fantasy written by a teenager who has read a lot of bad fantasy and has decided he or she can do as well.

I’m sorry, I wanted to give this novelette at least a rating of “mediocre,” but it doesn’t come up to that standard. Characters are forever intoning at each other stuff like, “You remember, Richard, you must. It was you who found the shining Sword trapped in the roots of the Cursed Black Oak in the middle of Gloomshadow Forest, where none of the Fair Folk could go. The Badger’s family helped you.” Capitals his, I swear. The story is full of “[Tybalt] carries a message from the Emperor of the Uttermost West, the King of the Summer Land” and “the cat washed his paws fastidiously” and “’Get out!’ Richard croaked.”

I can’t, in good conscience, give this a good review. I’ve tried reading it as a parody, and it doesn’t work that way, either. What was Van Gelder thinking when he bought this? Or is it just me? Not only is the writing bad, but the story is a mash-up of Narnia and other well-known fantasies. There’s not nothing new in this, and nothing worth reading.

Now to the short fiction. “The Avenger of Love,” by Jack Skillingstead, is an homage, an attempt to evoke the works of Harlan Ellison. Does it work? Yes and no… The story is about a man who discovers parts of his psyche missing; day by day something new is gone. In the course of attempting to find out why and where, he travels into a different place, a cartoonish world where things are not what they seem (Well, really, are they ever?) At the end of the story, he is transformed, in an Ellison-ish way.

Is it a good story? Well, I would say it’s a little better than average; it keeps your interest engaged, it doesn’t stray much from its central theme. The characters are a bit cartoony, but it is, after all, a short. Does it work as an Ellison homage? As homage, probably. As Ellison, not quite as punchy… Remember endings like “I have no mouth and I must scream,” or “Some of these old games go way back,” or “Now we are in the Time of the Eye”… not up to that standard, nosirree. But overall, I think it was worth reading.

“Andreanna,” by S. L. Gilbow, is another SF short; this one about an android, or humanoid robot (since everyone’s definition of android is different, I thought I’d better define mine) that serves as a tour guide on Luna. The android (Andreanna by name, get it?) suffers damage and needs to be returned to the factory for repair. The story is in what we find out about the maker of androids and her relationship to her creations; the style is extremely clever, and somewhat reminiscent of the way Doctor Manhattan thinks in Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen… I don’t want to give too much of the story or style away, because I think you’ll like it. The ending may be a little weak, but that doesn’t really detract from the story.

And finally, “Stratosphere,” by Henry Garfield. A future sports story, set on Luna. (There appears to be a Luna theme in the stories in this issue.) It’s a throwaway short, about a baseball player who can’t appear to adjust to the changed rules necessary to play ball in a vacuum on a lower-gravity planet, and what he did there. Cute, but as Heinlein’s Manuel Garcia O’Kelly-Davis once explained to Mycroft Holmes XXX, “funny-once.” It was worth reading, but probably not one you’ll put into long-term storage.

EDITOR’S NOTE: With this issue F&SF switches to its new bi-monthly schedule. To read reviews of the January, February, and March, 2009 issues, click on the Print/Monthly link on the left side of this page and scroll down until you come to F&SF.