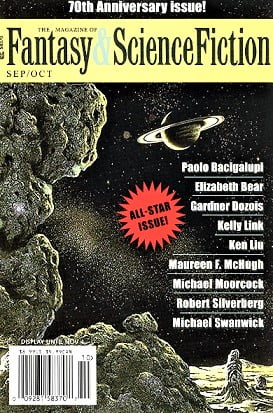

Fantasy & Science Fiction, September/ October 2019

Fantasy & Science Fiction, September/ October 2019

“The White Cat’s Divorce” by Kelly Link (reprint, not reviewed)

Reviewed by Seraph

“American Gold Mine” by Paolo Bacigalupi

If it is indeed the role of art not only to mirror life, but also to confront it in all its beauty and horror, Bacigalupi nails it. The time frame is now, give or take a few years, and the setting is New York City itself. The themes are as complex as they are timelessly simple. On the surface, it is a condemnation of greed and soulless pandering to the mob. But look deeper, and you see a darker vein pulsing, a hunger that has consumed kings and empires alike for all of history. Every dark impulse that haunts the human soul is on display, and the author has excelled at his art. Highly recommended.

“Kabul” by Michael Moorcock

This bleak, rather depressing tale is set in Afghanistan, in what seems to be the future after the worldwide collapse of government and order. I’d call it world war III, but it just doesn’t seem organized enough to be called a war. Mostly just conflicts worldwide and lots of opportunistic raiding. The full width and breadth of human depravity is on display, but with a strange amount of restraint. Most of the length seems a vehicle for commentary on various elements of interpersonal dynamics, an essay of sorts on the human condition post-apocalyptic. Beyond just being difficult to follow at times and oppressively lacking in any hope, it is a very gray and bland world that just feels…. Empty.

“Erase, Erase, Erase” by Elizabeth Bear

Elizabeth Bear here delivers a discourse on one of the darkest realities of human life. Whilst the time frame is modern, it isn’t specific, and the setting is an unspecified somewhere in America. The core concept revolves around recovery, healing and identity, but Bear tells the story of the pain that requires the healing. Specifically, what it’s like to be unmade by someone, to be abused, stripped of identity, and cast aside, and if it is even possible to return from that abyss. The answer, just as in life, is a tormented but resounding yes, and Bear leaves no doubt as to the severity of the pain and loss that need be mended. She manages to hit all the right notes of respect and compassion. No trauma is shied away from, but it’s all handled in a sensitive way that wouldn’t re-traumatize someone reading it who went through similar events. This is highly recommended, and exceptionally executed.

“Little Inn on the Jianghu” by Y.M. Pang

Pang offers a charming parody of martial arts epics, though to be fair, the absurd often comes hand in hand with the epic, so it actually feels quite well played. Set in a much-abused inn in the freewheeling Jianghu genre setting of Chinese literature, it is the story of longing, combat, and vengeance so common in that storytelling. This, however, is told from the perspective of the poor innkeeper, who is far more often than not in over his head. As he says, it almost always starts in an inn, and why, oh why, must it always be so destructive? If the pace of the story seems to jump abruptly, it is merely because the bemused innkeep just can’t keep up with everything happening around him.

“Under the Hill” by Maureen McHugh

Anytime an author writes about the Fae, I find it hard not to be suitably entertained. They are, after all, fascinating. The story takes place at a college, Burkman, of which neither the geographical nor temporal locations are offered, though it seems modern enough. It’s an interesting foray into the intersection of mundane college life, if there be such a thing, and the enchanting world of mystical creatures. The story is whimsical, fun, and certainly enjoyable, and fits well within the fantasy realm.

“Madness Afoot” by Amanda Hollander

Hollander relates a classic story, Cinderella, but from the perspective of the Prince’s sister, in the form of letters to her husband. It is a rather straight take on the whole affair, set far away in another time and place long ago, and without fairy godmothers and true love. It is, in fact, rather a cynical and jaded take, as one could imagine from the outside looking in as a skeptic. Rather than weigh the story down, however, it is quite well done, and is a realistic enough take that you can almost imagine the face of someone you know of whom the sister reminds you just a little too much.

“The Light on Eldoreth” by Nick Wolven

Wolven weaves a tale of paradise squandered. Set indeterminably far into the future, on a planet near the farthest reaches of the galaxy, it is a vision of suffering. It revolves primarily around the marriage negotiations between a girl’s father and the father of the potential groom, which mostly serves as a vehicle to expound upon the current state of humanity and how it arrived there. There is a great deal of pondering the meaning and pain and submission, as well as the cost of excessive luxury upon the soul. Like most philosophical pondering, it doesn’t really come to much of a conclusion, but rather raises questions to be answered. In that regard, it’s quite successful.

“Booksavr” by Ken Liu

In a piece that quite woefully reflects the current state of human intellect and society, Liu presents a recounting of an internet blog, set in the mysterious 20XX. The blog centers around the debate about an artificial semi-intelligence, an app which rewrites an author’s work to be more progressive and suit the reader’s personal identity politics. In what closely mirrors the constant state of twitter and internet politics as a whole, numerous comments on either side of the argument lay into the debate, with varying degrees of sense and vulgarity. As the preface claims, it is indeed a glimpse of a possible future of fiction. Whether it is one of encouragement or horror would seemingly rely on which side of the debate you come down on.

“The Wrong Badger” by Esther Friesner

Friesner displays an abundance of wit and sarcasm in equal measure in this satirical piece. Set mostly upon the futuristic theme park of EnglandLand, it follows the misadventures of a company girl in the midst of the (park) world plainly going to hell. What starts as a lawyer’s complaint about the lack of diversity in the park’s AI “actors” quickly devolves into an all-out revolt by renegade, reprogrammed machines, and resolves with the bankruptcy of EnglandLand due to the success of the chaotic and violent GlamMerica. It’s hard to tell at most points which topic is being satirized more, but it’s bloody good fun nonetheless.

“Ghost Ships” by Michael Swanwick

Like any good ghost story, this is one that deals heavily with the concepts of death and the impermanence of life. It’s set in New England, spanning several of the states in that area and quite nearly 5 decades, if I understood some of the references correctly. It is almost mournful, as if one were recounting memories after a funeral, but it’s hard not to see the love that is in those words. Whether it is a mysterious group of ancient sailors haunting a beach, or narrow escapes from untimely death, this is the story of friendship that spans a lifetime, and the questions that arise when one friend has passed on, and one still remains.

“Homecoming” by Gardner Dozois

It is hard to read this and not see echoes of art imitating life. Dozois, himself in his own last days when this was written, offers the story of a wizened old man carrying on throughout his last days in a quiet inn beside a river. Due to his staff and beard, many assume he is a wizard, and the truth is both far less and far more than that. There is no magic in the old man taking his meals quietly in the inn, but there is plenty in this story, set in what could be any little town deep within the realms of fantasy. There is great love, as befits high fantasy, and though it doesn’t come in the form most common, it is perhaps far more pure and meaningful, if ultimately doomed to fail. There is a quiet acceptance of death, and fate, but also the triumphant rebirth of new life. Truly exceptional work.