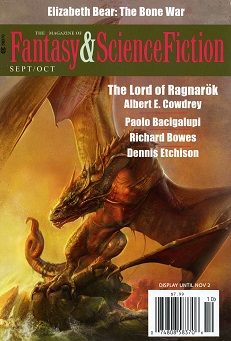

Fantasy & Science Fiction, Sept./Oct. 2015

Fantasy & Science Fiction, Sept./Oct. 2015

Reviewed by Jerard Bretts

This is another strong issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction, with a nice mix of veteran writers and young newcomers. The stories are varied too, employing a wide range of themes and subgenres. The quality is impressive with some stories highly recommended.

Albert E. Cowdrey continues to be a prolific contributor to the magazine, switching effortlessly from genre to genre. He’s not one to push the boundaries but always writes entertainingly. This time he contributes “The Lord of Ragnarök,” a fantasy novella in the grittily realistic Game of Thrones tradition, set in medieval Europe sometime after the Crusades. With some nice wordplay on the author’s name, it tells the story of slippery Sir Richard de Coudray and his rise from peasant boy to knight. One of Cowdrey’s major achievements here is to make us feel sympathy for this slippery and essentially Machiavellian character.

Nick Wolven’s “We’re So Very Sorry for Your Tragic Loss” imagines a society in which advertising is becoming more targeted, personalised and intrusive, while the jobs people do to buy the products being pushed at them become even more precarious and demanding. When the wired world acts on misinformation that Meg is struggling with a bereavement it plunges her into a nightmare “user experience.” Wolven uses humour to raise fundamentally serious questions about identity, authentication and what it means to be human. This is ultimately a very moving and thought-provoking story. I highly recommend it.

Bram Stoker wrote Dracula in 1897 and since then there have been many variations on the vampire theme. So how can a writer keep it fresh? David Gerrold both asks and answers that very question magnificently in his absorbing novelette “Monsieur.” Although the opening portion of a novel it works well as a self-contained story with a very satisfyingly clever ending. Another highly recommended story.

Ron Goulart’s “The Adventure of the Clockwork Men” is a second helping of the adventures of his Edwardian supernatural detective Harry Challenge. I have to confess I’m not a fan of this kind of cartoonish pastiche of the Sherlock Holmes stories. However, if it is to your taste you will find it skillfully written, with lots of incident, wise-cracking dialogue and humour.

I always look forward to stories by Richard Bowes. He writes elegantly and thoughtfully and has a wild imagination. Unfortunately, I did not find “Rascal Saturday” ─ the second in his The Big Arena cycle, according to the editor’s note ─ to be one of his best. This is set in an environmentally ravaged future Eastern United States and in the mysterious Naxos, “a city that had never appeared in any history or on any map of this world.” We’re introduced to a lot of different characters and locations in quick succession, without much time to get to know them. The editor suggests that one doesn’t need to be familiar with the first tale in the series to enjoy it but I disagree.

It is always a pleasure to find a story so brilliantly structured as Marissa Lingen’s story of fantasy and magic, “Ten Stamps Viewed Under Water.” Told in ten chapters, one for each of the stamps referred to in the title, it quickly creates an intriguing world gripped by plague. The characterisation is also very subtle and strong. Again, highly recommended.

Like Richard Bowes’ “Rascal Saturday,” Paolo Bacigalupi’s “A Hot Day’s Night” is set in an America transformed by the consequences of climate change. Also like “Rascal Saturday” it reads as if a fragment of a longer narrative rather than a self -contained short story, with unexplained references to “Merry Perry refugees” and other off-stage events. It is well written, but not satisfying.

Bo Balder is a well-regarded writer from the Netherlands and “A House of Her Own” is her first professional English short story publication. It is a very effective story in the tradition of tales in which colonists from Earth meet nasty ends at the hands (or other organs!) of aliens. There are enough imaginative twists in this variation on the genre to lift it well above the ordinary and it has a nicely creepy Northern European fairy-tale feel to it.

“Don’t Move” by veteran horror writer Dennis Etchison reads like Kafka crossed with Cormac McCarthy, propelled largely by dialogue and terse description. It is night-time and a man gets off a greyhound bus in the middle of nowhere, setting off a chain of bizarre events.

Finally, “The Bone War” by Elizabeth Bear is an enjoyable short fantasy that pits the wizard Bijou the Artificer against the scientific establishment. The descriptions of the bones of “Tidal Titan” and what happens to them are very well done.