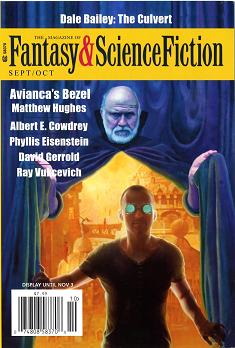

Fantasy & Science Fiction, September/October, 2014

Fantasy & Science Fiction, September/October, 2014

Reviewed by Martha Burns

“The Rider” is a story in which an AI named David learns what it is to be human via a deepening attachment to his human handler, Luke. This isn’t to suggest Luke is in charge. At the beginning of the story, he is merely the entity that exists in the physical world, acting on David’s behalf. David controls the shots, often literally. Those early episodes of violence are thoroughly enjoyable and set the tone of a good gunfighter yarn. Luke would prefer that they not have to kill people and he’s ready to retire as a rider or, like an older gunfighter, he’s ready for that one, last job and it is a worthy last job indeed, for neither Luke nor David wants the AI to get in the wrong hands or for the sentient operating systems the super-genius mad scientist made when he made David to take over the world, as they tend to do. It’s a common enough trope in science fiction that the reason computer systems want to take over the world is that they look at us as disposable, so one might suspect that Luke teaches David to care, but that isn’t quite it. David always cared, but he was missing some component of how to care. David doesn’t realize that humans are individuals and when he realizes that the crux of humanity is our individuality, David’s caring becomes more personal and he and Luke now have a relationship closer to that of equals. Put another way, this is a romance, which Jérôme Cigut acknowledges in a last, wry comment. In this story, we therefore have a fun continuation of “the last job” trope in which the gunfighter goes off into the sunset, but here he goes off with a buddy and not a babe. and the buddy in question is all gears and sprockets. Read that way, the story is thoroughly enjoyable, but do beware. This is not a meditation on what it means to be human in the way of “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?”. David’s epiphany about humanity is not the point and if it were, the story would not work because that we view ourselves as individuals is not much of an epiphany. As long as Cigut sticks close to the gunfighter trope and as long as readers keep their expectations on that level, a good time will be had.

“The Caravan To Nowhere” by Phyllis Eisenstein introduced me to Eisenstein’s work despite her standing in the field. I strongly suspect that new readers will wonder where she’s been all of our lives and be disappointed at how difficult it is to find her work. Her stories have been nominated for Hugos and Nebulas and this reprint from Rogues, a recent anthology edited by Gardner Dozios and George R. R. Martin, shows why. Sadly, an Amazon search brings up only used copies and no Kindle editions. In this story, Alaric, a wandering minstrel and recurring character in Eisenstein’s larger universe, joins a merchant on his journey to harvest a mysterious drug, Powder. The drug has made the merchant’s son an addict and part of Alaric’s job is looking out for the young man, who tends to wander and rant. The son, Rudd, believes he can get to a city that will grant him his heart’s desire and the mystery at the crux of the story is whether there is such a city or not. While we wait for the mystery to play out, there are evocative scenes of traveling through the desert, intrigue between the merchant and his workers, and the opportunity for Alaric to display his ability to blink through space. The end of the story promises a continuation of Alaric’s wanderings and I predict readers will eagerly await the next adventure and hope the publishers of this world put it in our way.

Albert Cowdrey‘s “The Wild Ones” will speak to parents everywhere. It begins, simply enough, with a spaceship of miscreants off to colonize or, rather, to recolonize the Earth that prior generations have destroyed. Things are quite well on the planet, thank you, but nature’s become even more red in tooth and claw than she was the last time we were here. Never fear, though, because the would-be colonists have The Biter. You know The Biter. He’s the bane of daycare, the little fiend who makes every parent who is not so cursed thank the universe. Yet, blessed parents (I know, I was one) suspect The Biter will not end up in prison, where he belongs. We have the suspicion that he and all of his choppy minions will be the ones that wind up running the world. This story shows we are right. The story is funny, filled with clever wordplay, and gives us back a little bit of Douglas Adams, albeit with teeth.

The question I could not quit asking regarding “Avianca’s Bezel” is, Why a bezel? A bezel is the part of a ring that holds the jewel, the part that looks like a spiked cup. Raffalon’s job is to steal a magical bezel from a witch, Avianca, and while stealing a magical item from a witch is a worthy pursuit and Raffalon is the right thief for the job, why a bezel? It’s like going out to steal the socket of a candlestick, which is the little cup part that supports the candle. It finally occurred to me after I’d asked myself, Why the bezel?, ten or so times that the bezel points to the ideal reader for this story. “Avianca’s Bezel” is just as funny as Cowdrey’s “The Wild Ones,” but its progenitor isn’t Douglas Adams. The humor in “Avianca’s Bezel” is the kind Terry Pratchett made famous and, like Pratchett’s sense of humor, it most often shows up in tales about silly wizards and clever outlaws. Matthew Hughes‘s protagonist is one such clever outlaw. The wizards are not only silly, they are clueless and snobby. In fact, everyone other than the hero is clueless and/or snobby. For example, the people who control the town our luckless hero finds himself in have a Kafkaesque prison system and even the marauding lizard whose job it is to guard the bezel isn’t clear on how to do its job. The motif of worldwide idiocy can be annoying, but if you enjoy Discworld, you are sure to enjoy “Avianca’s Bezel.”

Emmet-Murray is a troll and he stinks. He makes mounds in the back yard, is demanding, and is, in general, the houseguest from hell. Our hero, a writer, feels that if he’d survived his son’s teen years, he could survive anything, but no. Trolls are worse. Our clever writer wound up with the troll through the meddling of an annoying friend and, due to zoning laws and statutes geared toward the protection of endangered beings, cannot evict the troll. “The Thing In The Back Yard” by David Gerrold shows how to do that, should you ever need to and, along the way, supplies zippy dialogue and amusing asides on the lives of writers, parents, homeowners, and a well-deserved critique of the public’s misplaced love of causes. This is magical realism at its best.

The fabulous “Marketing Strategies Of The Apocalypse” by Oliver Buckram deserves an emoticon rather than a review. It deserves a combination of a hug, a wink, and a smile. The very short piece touts the virtues of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction by reflecting on the glory of product placement, which still exists after civilization as we understand it stands in ruins.

In “Sir Pagan’s Gift,” a genderless voyager from a hive society faces “er” execution (Tom Underberg uses genderless pronouns throughout) at the hands of angry, human villagers. The voyager, who the villagers call “Sir Pagan,” figures out that the poverty-stricken village isn’t unlucky, as it seemed at first glance, but is being oppressed by a group from within. The voyager sees through the ruse with the help of The Book of Flame, a religious text written on the bottom of er tongue. The execution is set to go off when a bishop arrives and the questions are, first, whether the voyager will be freed and, second, whether the voyager, if freed, will share the true reason the village is so poor. It isn’t so simple because each decision yields problematic results the voyager foresees. In short, the question is, What will be the gift? The story handles the intricacies of a religion with its own understanding of causality clearly. The result is that the exact form of the gift isn’t something one is likely to predict and yet makes perfect sense. My sense is that the alien world Underberg creates is fully realized somewhere, but I wished the piece had been longer so that I could have appreciated its intricacies in the story. I felt what we got was the tip of the iceberg rather than an ice floe, but as I couldn’t make out the shape of the iceberg, I couldn’t be sure.

“Other People’s Things” by Jay O’Connell is sincere. In the wake of the recent California shooting spree by a young man who decided to kill because he couldn’t get a date, a story about a nebbish who gets a genuine clue about why he can’t get a date should be good news. The protagonist, Chris, goes to an image consultant. This is the fictional analog of the self-help gurus who go by the name Pick Up Artists who we’ve learned about since the shootings. O’Connell’s image consultant is not smarmy like those guys, though. Instead, he’s a hoot. He tests Chris’s level of body odor and gives him an empathy pill. Those early scenes are funny and show promise, but suspicions start to appear when the image consultant deconstructs a recent interaction Chris has had with a new coworker. She gets bored and then begins to hate Chris when he keeps talking. This is yet another reference to a phenomenon that has come to consciousness in light of the shootings. It’s called “mansplaining,” but O’Connell gets it wrong. He has the coworker hate Chris because he goes on and on about things she doesn’t understand, such as, in this instance, Internet security. Mansplaining is being talked to about something one already knows or, in the worst case, about something about which one is an expert. That phenomenon points out something about a man’s character, not about a woman’s knowledge or interests, and that is the insight O’Connell promises—male character development—but does not deliver. Suspicions deepen further when Chris begins to have success with a pretty, blonde, buxom woman he meets at the gym. Suspicions are confirmed when it turns out the blond, buxom, vegan feminist has had plastic surgery because she is . . . just as much of a self-hating misfit as Chris. Again, this is sincere, not snark (I looked on the author’s blog to be sure because one wouldn’t want to misunderstand male sincerity), but it’s not the way to make the point O’Connell wants and, more crucially for the story, keeps us from getting inside Chris. It’s a shame. Chris seemed sweet and I wanted to see how he changed, not how the universe provided him the right catalyst.

Douglas’s twin brother goes missing and it destroys Douglas as well as his family. What happens is that one day, the brothers go into a series of tunnels and then one day only one comes out. “The Culvert” by Dale Bailey is much more than that, though. The tunnels themselves are pure Italo Calvino that shift and change and as they shift and change, questions about what it is to be an individual come to the fore. The story is never forced, either emotionally or philosophically, and we feel for the character not as a boy who lost his twin, but as a person in search of their true selves and doomed with the eventual realization that no such person is ever to be found.

“Embrace Of The Planets” by Brenda Carre is part bibliophile fantasy, part Doctor Who, and part The Old Curiosity Shop. Eleanora Watson, a writer who was disabled by an accident years earlier, is having a bad day and hopes that she’ll finally be able to check out that antique store with the funny sign—“Mostly Closed.” That fateful day her world and future career changes, the shop’s sign says “Open by Inter-Planetary Agreement.” Inside, Eleanor finds an anglophile-francophile wonder and a bent little man for a proprietor who just happens to be reading a long-lost book by Jules Verne. The man is not what he seems, the book is better than one could imagine, and Eleanor, while frightened at first, embarks on a new life of adventure. I predict most readers will want to join her and, since we can’t, we’ll be happy to have been privy to her new life.

The introductory blurb to “Will He?” by Robert Reed says readers won’t like it if they only like stories with pleasing characters, but who likes those? Give me a good, nasty, evil villain any day. Alas, Adelman is not nearly bad enough. He’s not nice to be around, but he’s not menacing despite being a misogynistic drunk with a plan to release a disease that will wipe out humanity. What’s missing are scenes of nastiness, true nastiness, and without those, Adelman is just one more crank with a vial of plague.

“The Way We Are” by Ray Vukcevich makes fun of how hard it is to communicate and explains why, against all advice, I have the same password for all of my important accounts. In both instances, knowing more than two things is a problem, especially in romantic relationships where we are supposed to be tuned in to the other person, but they simply won’t tell us what to say to make them happy. Darn them. The narrator does eventually figure out his beloved password, but we have a clever parrot in a restaurant to thank for that. If I had one sitting on my desktop, maybe I could come up with something more inventive than my dog’s name to get into my bank account.