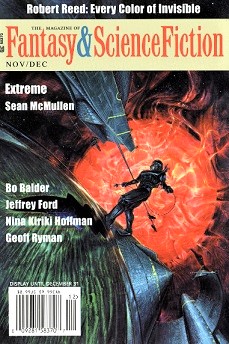

Fantasy & Science Fiction, November/December 2018

Fantasy & Science Fiction, November/December 2018

“Thanksgiving” by Jeffrey Ford

Reviewed by C. D. Lewis

This year’s November/December issue of Fantasy & Science Fiction offers eleven new pieces. They span the gulf between hard SF and light fantasy, and between gritty darkness and comedy. Something for everyone.

Jeffrey Ford’s “Thanksgiving” is a creepy short fantasy about a family that realizes the “Uncle Jake” who’s attended Thanksgiving dinners the last fifteen years isn’t, in fact, related to anyone there. Richer in description than story arc, the work’s strength comes from a combination of anticipation (he’s sure to find them when they move the event, because it’s a creepy fantasy) and reveal (everybody’s got a theory about his real connection to the characters who get the screen time). Ford provides a solid reason to keep your family events small enough to tell whose family the various attendees really are.

Y. M. Pang’s “Lady of Butterflies” presents a romantic fantasy about a young foreigner found unexpectedly in the Imperial compound. Narrated by the sword-bearer assigned to oversee her on the premises, the short story doesn’t use the word samurai or bushido but gives the impression of Japanese warrior culture superimposed on a land where women frequently held positions as knights and the land was once ruled by an Empress with an enormous harem of consorts. Beautiful descriptions carry the reader through the narrator’s growing attraction to the stranger whose novel magic proves to have a cost that ultimately explains the story’s open. The easily-understood phenomena of witch hunts, womanizers, professional pride, and the emotional power of new love make an easy sell of the story’s problems and their solutions. The story’s strengths include magic-feeling magic, readily understood characters and stakes, a believable climactic decision, and vividly depicted images that inspire the narrator’s believable wonder. Recommended.

Sean McMullen sets “Extreme” in an SF world in which the narrator, genetically predisposed to high risk thrill-seeking behavior, masks his personal locator from police to seek lawbreaking thrills. The SF elements put me off: extraordinary edge-of-the-bell-curve character traits don’t feel believably explained by a gene found in forty percent of the male population. Once that doubt is established, elements like while-you-wait genetic analysis reminds one more of CSI episodes that prioritize the writers’ plot ideas over realistic science. In favor of plausibility, however, is the story’s solid explanation of the narrator’s access to the resources required to perform the stunts depicted in the story: his psychological condition yields a confident presentation that in his day-job makes him an effective and highly-compensated salesman. The story’s resolution fits the character, stranding him in a world where he’s doomed every day to face worsening odds to survive. The dark double-cross suits the character, his employers, and the final disaster: he’s been left alive in case he’s later useful to the one-percenters who’ve engineered the pandemic sweeping the world, and against which they’ve had him inoculated. We know what his next source of excitement is likely to be…

Translated from the original Czech by Julie Novakova, Hanuš Seiner’s “The Iconoclasma” multiple-third-person SF opens on a flashback to a ship under attack while orbiting a red giant. The enemy–sentient beings brought into humans’ universe by a class of geometric images anyone can draw–appear inscrutable and deadly. Seiner’s rich descriptions include the view from exoplanets, images of starships in combat with alien intelligences, and other details calculated to please and excite SF fans. Multiple POVs showcase Seiner’s world from different characters with different stakes, different quirks, and different phobias: the attacked ship isn’t so much about a growing repair list as it is, for example, about an iris airlock’s creepy lamprey grin in a lonely access tube–or the regret the familiar ship will be lost, and the tragedy this happens just as the repair crew became responsible for the whole thing. Viewpoints from a planetary station provide further perspective on the developing disaster, and what it means for humans far beyond those aboard the doomed ship. The flashback is interrupted with worldbuilding snippets about the icon-based life forms, their discovery, and the eventual dependence of humans on the topology-driven effects they can be exploited to create in the world humans can perceive. Eventually Seiner delivers a countdown-driven climax that combines envelope-pushing intellectual effort and technical expertise (building physical objects from debris in microgravity) to showcase a celebration of skill, sacrifice, and interdisciplinary coordination–a gorgeous SF fest the genre’s readers won’t be able to help but enjoy. A dark denouement offers a dismal view different from the early, optimistic SF on which many readers were weaned: humanity turning from knowledge out of fear. If you love the look and feel of SF, you’ll want to read this.

In 123 words, Abra Staffin-Wiebe’s “Overwintering Habits of the North American River Mermaid” offers an alternative perspective for those ghosted after a short relationship. Entertaining. Extra points for bang-for-the-word-count.

Robert Reed’s “Every Color of Invisible” is a fantasy novelette over 13,000 words set in a hidden Lakota community where the author set five prior stories involving the character Raven Dreams. Prior knowledge of the preceding stories may be important to best enjoy this work. The italicized introduction gives little information about the characters it mentions; it doesn’t seem to put the story that follows into context so much as bewilder newcomers about what facts to try to carry forward into the next section of text. At the outset, there’s little indication what Raven wants or what’s at stake for any of the characters, which makes it difficult to understand what results to hope for or discern why one should care: we see characters’ exteriors, and have precious little clue what to conclude about their desires and motives. Another concern: the mythic use of titles instead of proper names for many of the characters leaves one uncertain whether some of the titles might refer to the same character. Is A also C? Not knowing who was who, I found myself wondering in spots. Greater familiarity with the characters from earlier stories might give a stronger sense of their interiors, their values, and the import of observable activity. Non-chronological presentation complicates the effort to discern who knows what in which scene, and hence cause and effect. Story aside, the world is fun: Lakota live in a hidden world awaiting return in better days, non-natives are ‘demons’ and computer-related terminology is presented as alien jargon to an aspiring shaman. Reed leverages Raven’s outsider-viewpoint to make entertaining comments about the world we know and those who live in it. The dismal-future of AI-assisted war machines and identity-spoofing Internet anonymizers juxtaposes entertainingly with a youth aspiring to become a shaman, recalling cyberpunk/fantasy mashups like Shadowrun. Questions about which world is real always make for a good time in a universe that offers characters access to artificial worlds. An us-versus-them backdrop supports great feel-good moments, such as when the protagonist takes care of an ‘enemy’ who’s an us before looking after a sympathetic them. The story’s most enjoyable elements gather with greatest density in the final third–personal motivations suggested, worldbuilding questions answered, and so forth. The last third also provides physical confrontation, interpersonal conflict, and a scene resolution that involves some emotional force one could take for a climax. Readers who enjoy a slow journey of discovery may find the piece to their taste.

Set in southern California, Geoff Ryman’s fantasy “This Constant Narrowing” reverses gender role stereotypes to paint a portrait of a protagonist suffering from the toxic attention of a man with no clue how to act like a civilized human in a world full of people who don’t want a romantic relationship with an evil nut. The fantasy element is that all the women have disappeared, so the evils men visit on women are now routinely visited on other men, who are the only remaining sex objects. A straight male reader, presumably, is intended to sympathize with the protagonist and experience alarm that a man with no intention to take no for an answer is stalking him, and is armed, and that everybody in town thinks this behavior is entertaining or even sweet, and asks if the man who shot him is good-looking or drives a nice car. The piece gives rich description of the protagonist’s gritty life. We observe remaining humans’ treatment of each other as more categories of people vanish (transsexuals, then homosexuals, and onward). Individuals get lonelier and more isolated. It’s intentionally dark. Eventually the frequency and intensity of abused-lover tropes pushes the reader into a decision whether the work lampoons the idiocy in commonly heard responses to pleas for help, or represents a work of horror centered on the growing dependency of the protagonist on men who run the hospital, men who have been hospitalized by other men, and/or men who are in the hospital to continue an already-initiated pattern of abuse. The story seemingly seeks to explain for those who have not paid attention to violence against women what it looks like and why its targets do some of the things targets of violence do. Like a Rorschach test, reactions to the story’s second half tell the reader more about the reader than the world it depicts. As suggested by its trigger warnings, it may not be an experience for everyone.

Nina Kiriki Hoffman’s “Other People’s Dreams” is a fantasy narrated by the apprentice of a dream shop proprietor who caters to the discriminating customer. It’s rich with nostalgic images of lost family and distant hopes. The hands-on description of the characters’ dream-crafting is fun and the stakes are worrisome and the climax and denouement are delights. Reuniting, reconciliation, peace, appreciation, and reward are apparently not dead in modern fiction and you can get your fix here. Recommended.

In “The Baron and His Floating Daughter” Nick DiChario presents a fantasy in the tradition of Italian folklore. It’s a black comedy, a tragic love story, a triumph of justice, a satire on government, and all kinds of delicious things rolled into 5,844 words. Something for everyone, an easy read, and thoroughly enjoyable.

J.R. Dawson opens the dark SF tale “When We Flew Together Through the Ice” on a planet whose narrator enjoys running barefoot in the rural outdoors, fearless of peril, thrilled by the natural beauty around her. She doesn’t understand her mother’s actions, and when the protagonist inadvertently exposes her mother to the risk of discovery she’s faked all their deaths to escape the narrator’s dad, her mother has an implant added to her daughter’s brain to ensure she cleaves to her mother’s idea of safety. The carefree girl, full of joy? Gone. Dark life with the implant is an interesting read: is it lying to you to con you into something it was programmed to make sure you did, or is it looking after you despite your objections? Is it a paranoid nut, or conscientiously tracking real problems to save your life? If SF mental health thrillers were a thing, this prop would be their star. The implant comes off as driven by compulsions, or trying to drive people with them–and possibly more concerned about its own safety, or its purchaser’s, than its wearer’s. Beautifully dismal dark SF.

Bo Balder’s fantasy “The Island and Its Boy” turns on the lifecycle of islands circulating in the oceans of a gynocentric world where a boy didn’t have a lot of prospect. The story’s opposition comes from so many sides–protagonist’s gender, the hierarchy of families, the seniority of fathers over boys, the etiquette controlling marriage negotiations. “The Island and Its Boy” combines a chosen-one character driven to break with tradition with an exploring the unknown objective in a society outwardly committed to protecting its status quo to the point of death. Warmth, camaraderie, and fondness provide surprise relief. An enjoyable short hopeful fantasy.

C. D. Lewis lives and writes in Faerie.