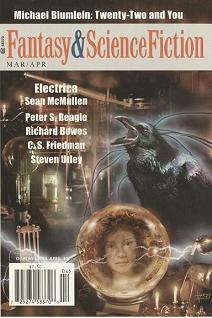

Fantasy & Science Fiction, March/April 2012

Fantasy & Science Fiction, March/April 2012

“Olfert’s Dapper Day” by Peter S. Beagle

“Twenty-two and You” by Michael Blumlein

“The Queen and the Cambion” by Richard Bowes

“Greed” by Albert A. Cowdrey

“Perfect Day” by C. S. Friedman

“Gnarly Times at the Nana’ite Beach” by KJ Kabza

“Demiurge” by Geoffrey A. Landis

“Electra” by Sean McMullen

“One Year of Fame” by Robert Reed

“Repairmen” by Tim Sullivan

“The Tortoise Grows Elate” by Steven Utley

“The Man Who Murdered Mozart” by Robert Walton and Barry N. Malzberg

Reviewed by Aaron Bradford Starr

It’s difficult to describe the overall impression of the March/April 2012 issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction magazine. The stories are varied, as usual, but seem to hew to an overarching theme of disconnection from one’s own surroundings, and the many difficulties this causes. Among the difficulties, unfortunately, is all too often a dislocation of narrative that makes some of the stories of this issue real work to get through, and the group ends up being carried on the strong backs of the relatively few stories that truly shine. But among those stories that do, there are real dazzlers.

A fine example of the challenges some of these stories present to the reader is “The Man Who Murdered Mozart,” by Robert Walton and Barry N. Malzberg. Told in a highly stylized fashion from the very opening, the story eschews many standard practices, indulging in an omniscient third person presentation, which, when combined with the all-encompassing social critiques sprinkled throughout, quickly hobbles all attempts the reader may make to either sympathize or empathize with the cast. In the later sections of the story, this proves a fatal combination.

Though centered around the abduction of the dying Mozart by a powerful, self-indulgent man of privilege from the far future, named simply Beasley, Walton and Malzberg rarely give us any demonstration of character, instead content to merely tell us how a character is feeling or what they might be thinking. This is not done through an amateurish lack of skill, but as a literary technique, meant to heighten the gulf of social norms between our time and Beasley’s. A superficial man for a superficial time, as the story tells us.

This lack of connection runs through the entire structure of the story, making first Beasley the protagonist, then focusing on a certain Dr. Richards, and lastly following the post-abduction exploits of yet another character in whom the reader is even less invested. The details of location and the flow of events is glossed over, except, strangely, in the few fight scenes, which we get to witness in blow-by-blow progression. The story gets especially fuzzy during the scenes in the past, muffled under layers of narrative naval-gazing and characters talking about doing rather than actually doing.

Though impressive on one level, “The Man Who Murdered Mozart” is, ultimately, a slog, grinding to a halt under a cargo of too many weighty pretensions. Some of these flaws are shared by the issue’s closing story, “Olfert’s Dapper Day,” by Peter S. Beagle.

The tale starts out enjoyably enough, moving lightly and quickly through the circumstances that send Dr. Dapper to the New World. But “Olfert’s Dapper Day” has something of a tone problem as well as a pacing problem. The story is neither light nor quick, and the almost whimsical tenor of the opening (including the title) quickly gives way to a more somber note. This would be an acceptable shift in emotional color if it weren’t accompanied by a slowing tempo that makes the center portion drag somewhat. The overall effect is to create doubt in the reader about their understanding of the characters and their motivations, and perhaps the author senses this, as it is about at the midpoint that the motivations of the characters become more forthrightly revealed in exposition.

The blend of mythical creatures, the natives of the New World, and Old World cynicism become hard to sustain for as long as the story runs. While unique and ambitious, “Olfert’s Dapper Day” stumbles badly about midway through, and doesn’t find its legs again before closing.

The motivations of the protagonist in Michael Blumlein’s tale, “Twenty-Two and You,” in contrast, are clearly delineated in the opening paragraphs. The clarity of vision presented here is striking, as a young woman wrestles with the genetic predisposition for cancer should she become pregnant, and is presented in the stark light of current genetic findings, and the rather Cyclopean curse they bring. The future can sometimes be known, but only if you make a terrible tradeoff, and what is foretold is the manner of your death.

The speculative elements are narrow but pointed: there exists a technique that can repair what nature has wrought poorly. It works. But the dilemma lies with the nature of the problem: genes are their own environment, and if you alter one, you alter what the others will do. The woman’s choice is clear: a child at the cost of life cut short by cancer, or some other, vaguely hinted at problem? The choice almost makes itself.

The unknown consequence that lies within the known result of the treatment is the crux of the tale, and the brevity of the tale leaves Mr. Blumlein little room for elegant structural maneuvering. The doctor outlines the risk verbally, and illustrates it with a lengthy anecdote that drowns out the narrator’s own voice just as we need to hear her thoughts. Worse, this disconnect is repeated in the resolution, where this same doctor relates the result as an anecdotal warning to some other couple. The tale, so poignantly sketched early on, deserves better, and loses much of its power as a result.

The narrative voice of Richard Bowes’ entry, “The Queen and the Cambion,” is similarly distant, but the choice of affixing firmly to the viewpoint of a young Queen Victoria as she lives her life serves us well. So much ground is covered, and so quickly, that it is the personality of the famed monarch that the reader clings to as we experience her numerous meetings with the enigmatic Merlin, of Le Mort d’Arthur fame.

Clearly, in the format of the short story, we can do little better than skipping like a stone over the details of both these figure’s lives, but the tale lays such a strong emotional groundwork that this feels proper. We are not here to learn the details of their everyday existence, only the heart of the interplay between the Queen and the Cambion who rashly vowed to serve the monarchs of Britain. This story is masterful, and serves as the first gemstone in this issue.

In “Greed,” Albert A. Cowdrey has taken the exact opposite literary tactic, immersing us in the strange but dreary life of a man, Vern, overseeing the faded grounds of a manor owned by a rich uncle. But all is clearly not right, as the first sentence indicates. Vern chomps at the bit, bound to remain in service to this crumbling estate. The wealth the property implies is not his own, but lies in trust. The man, too, after his long service sequestered away from the bulk of humanity, is losing perspective on whatever morals he may have once had. And, of course, there’s the creature that needs, occasionally, to be fed.

If there were a contest to wrest the moldering crown from the brow of Edgar Allan Poe, Albert Cowdrey could offer this piece up as the price of entry to the competition. An untrustworthy narrative view suffuses this piece, and the complete lack of any discussion of morality are strong echoes of Poe. Albert’s character Vern is driven so strongly by imperative that he never really questions his place in the spectrum of right and wrong.

All is not perfect here, though. Cowdrey’s choice of a less-than-clever protagonist is a difficult one, especially for a writer who seems very much the opposite. Vern often sounds and acts intelligent, and so the repeated reminders he isn’t are somewhat hard to fully accept. And, more critically, the short reach of the protagonist’s wits are only easily evident when he makes the mistake that proves his downfall. The error is obvious, and leeches much of the power of the twist when it is revealed.

Presenting an entirely unique take on social disconnect, we are treated to “Perfect Day,” by C. S. Friedman. This is an unsettling vision of one of the futures that rests, serenely balanced, on the present day in 2012. This is cyberpunk for the modern age. This is, for all its smooth presentation, a technological horror story, where society has so embraced its intrusive gadgetry that humanity finds itself trapped in a web of competing offers, self-administered incentive programs, and corporate-sponsored augmented reality.

As terrible as the image is, it is a pleasure to read, keeping a tone that balances the ridiculous (and completely plausible), with the introspective and borderline neurotic. The story is an effortless read, built for rapid consumption, but lingering, only fully coming clear when the entire piece has been taken in. It is a rare story that can capture the immediate and ephemeral and meld it with a longer view, but “Perfect Day” may well have done just that.

As is so often the case in this issue, the next story offers a sharp contrast. Boasting the clever technological innovation of “smart sand,” “Gnarly Times at the Nana’ite Beach,” by KJ Kabza, tells the story of Dusty, a would-be surf god hobbled by the narrowness of his times. The beach has been transformed into a wireless extension of the internet by the smart sand, which are micro-transceivers and display elements all in one, making what was once the domain of the real world a pixilated and shallow image of that world. The surfer ethos of existing in the moment, of experiencing a heightened sense of reality through the effort and skill of contending with the power of the ocean, has been corrupted by the sand’s influence over experience. The augmentation of reality has degraded it.

The thematic elements of the story are strong, and thus it is jarring when the execution stumbles. It often does so when describing the perceptual contents of the augmented-reality visions everyone has overlaid on their normal perceptions. Their efforts to understand what they are seeing muddies the reader’s own hard-crafted mental imagery, and often leads to doubt as to what something should look like. When dealing with the hallucinatory images in water churned aside by a surfboard’s wake, for example, it is best to be clear.

Also, the characterization and setting is likewise strikingly off-kilter at times. Dusty, the protagonist, is presumably in his late teens or early twenties living in the near future, and yet the language he and his friend use for banter is that of a junior-high schooler from a different time. Often the narrative seems unreal, like it’s taking place in an alternate 1985, with girls watching music videos and words like spaz and gnarly being in current use.

But the expected is also defeated successfully, as with the character of Zhaoping Ho, a surf god and board-making master. His expected chill, laid-back attitude is wholly lacking, serving as an incarnation of all that has gone wrong with the surfer-ethos after technology was melded with the beach. Driven by technological yearning, Ho seeks to hack the waves by tuning into the water-borne smart-sand.

This corruption of the spirit of the outdoors is the most powerful aspect of this piece, and makes any flaws in presentation minor concerns. Mr. Kabza tried to do a lot with this story, and mostly succeeds, delivering a denouement that works because Dusty finally comes into line with the reader’s expected reaction against the invasive technology that has so ruined this setting.

Falling on the more forgiving side of the less-is-more line, we have “Demiurge,” by Geoffrey Landis. If haiku could be several hundred words long, “Demiurge” could be considered a shining example of the form.

Relating the possibly-true tale of a minor science fiction author and his lasting legacy, this story is a fine example of understated emotions, conveying hope and mystery within all the trappings of futility and despair. The tale can be filtered though any number of lenses, from Christian thought to Scientology, and will look very different through each. But its lack of cynicism makes “Demiurge” more than social critique, and elevates it to a genuine example of finely written art that serves a purpose.

Continuing along this road is the spectacular “Electra,” by Sean McMullen. I usually highlight an exceptional story from each issue of F&SF as the one that makes the entire issue worth buying. But Sean McMullen’s offering may well justify the price of an entire yearly subscription.

The tale transitions seamlessly from written letter to first-person narrative, and in doing so effortlessly avoids clumsy formulations and entirely unbelievable passages of exposition and dialogue for the rest of the story. Starting off in a workmanlike fashion, we are introduced to one Major Scoville, a code breaker in the service of Britain during the Napoleonic Wars. With all of the historical detail and atmosphere, it is, at first, possible to miss the apt characterization and finely tuned setting. But the building tension is impossible to miss. As if military strategy at the dawn of the Industrial Age weren’t intriguing enough, we are treated to something more. And more and more.

Normally, the anatomy of such a well-told tale would be laid out, for the consideration of individual parts. It is only in service to this story that these details are not studied closely, for they are intricate and in constant motion, like a pocket watch that keeps perfect time, and worth leaving for the narrative to reveal. It must suffice to say that from the opening arrival to the closing speculation, “Electra” is masterful. This is a story not to be missed, and Sean McMullen is an author to keep a close eye on.

“One Year of Fame,” by Robert Reed, is a smaller scale story, yet proposes an interesting premise, wherein artificial intelligences abound. This could well take place in the same setting as Reed’s excellent story “Firehorn” (published in F&SF in 2009), as it has the same intriguing AI, and gentle optimism. What makes Reed’s AI so endearing is their human-like fascination. The central character of “One Year of Fame,” known as Old Kevin around his small town, becomes the object of the people’s interest after a recent cognitive upgrade allows him to appreciate the subtleties in written fiction. So enamored of Kevin’s small body of work do they become that he develops an entirely spontaneous cult of personality, all within the society of the AI, who obsess over his every sentence, and re-read his collected body of work frequently.

Reed’s ability to distinguish human fanaticism with its machine-bound counterpart is done through the concept that Arthur C. Clarke would have approved of as a counterpoint to his own take on social evolution presented in Childhood’s End. The AI of “One Year” are subject to a software upgrade cycle, and this serves as both the inception of the story’s events, and their resolution (through a further upgrade), and makes the story linger in the mind after it is over. With the profound changes taking place in the quality of their minds, what will these fellow inhabitants of Earth do with their culture? Also, the nature of the upgrade is never touched on, nor is the agency that conceives and performs the alteration, and these are tantalizing mysteries that hint at a larger, richer word beyond the story’s confines. “One Year of Fame” is a bigger story than its word count would suggest, and is a real pleasure to read.

Another small story, “Repairmen,” by Tim Sullivan, also hints at larger things, but does so by forthrightly telling of them. Aiming for a melancholy tone, the story involves a single encounter with a bereaved woman and a friend of her deceased love, who has recently committed suicide. Told mostly through an extended dialogue, the premise of the story is clearly set out, but this structure presents problems.

First off, the technical details the friend provides are jarringly out of balance with the protagonist’s mental state. While she exhibits all of the expected growing anger and outrage at this, her words ring hollow, as we the reader cannot sympathize too much. We want to learn some detail, and she’s keeping us from it. Bereaved or not, her entirely appropriate reactions slow the story to a deliberate pace, but at a cost. We are relieved when her visitor bristles, allowing the character to realize what a pain she’s being, and finally stop her protestations.

The second problem with the story is that relies on deep theoretical physics, specifically a variant of M-theory called “Brane Theory,” which proposes that the universe is a large 3-brane, or a three-dimensional membrane. For those familiar with super-symmetry and modern string theory, the details present few problems, but it’s fair to ask how small an audience this may be. Whatever the number is, it is a challenge to present details of modern physics in a single conversation with those in grieving, and makes for some rough sledding, simply because the protagonist is in no mood for the sorts of details that might make this premise understandable to her.

But the smooth, gentle tone of her visitor, a Repairman of the strings that link branes together, helps in this respect, and the understated bits of technology that Mr. Sullivan allows us to see hold the story together. It is a story that perhaps tries to do too much in too little space, and this is a forgivable flaw, and far preferable to its opposite. Even those left dissatisfied will likely find themselves wishing there were more time to explore this universe, and that’s the sort of criticism most could live with.

Unfortunately, “The Tortoise Grows Elate,” by Steven Utley, is just such an example of saying too little in too long a tale. “Tortoise” is so sparse in relevant details, and so divorced from its setting, that, when it ends, the impression is simple bafflement.

Before getting to specifics, it should be noted that Steven Utley shows great utility with academic detail, inserting quotes, literary references, and assorted scientific bric-a-brac with abandon. Unfortunately, this is placed on shaky foundations, and makes getting oriented as a reader very difficult. For example, the story tries for a brief in media res opening, but, given that the reader has no clue as to where, when, who, or why anything is happening, it falls flat. The reader is presented with characters like the Paleo Boys, Acid Drip, and the Wasp Woman. Time travel is hinted at, and an expedition is laid out. It isn’t until page three that it becomes clear that the Paleo Boys are actually Homo Sapiens with nicknames, and not, as their dialogue or the narrative voice might lead you to believe, Australiopithacus or something similar.

Thus the opening pages are a swirl of confusion as one mental misconception gets traded in for another as the cast is solidified as being a group of paleo-biologists going on an expedition through time to the Paleocene. The snarky narrator continues to confound, forgetting that her audience must, at least at first, take her at her word. It is only as the essential immaturity of her and her companions becomes clear that we realize how relatively unreliable she is, and by then it’s far too late for first impressions.

I know a relatively large number of academics, in varied fields, and cannot reconcile the caricatures Mr. Utley provides with any living example I’ve met. The presentation of scientists as either sexless toads, horny geek fratboys, or sexy-yet-aloof brain-chic types is little more than a tired retread of worn stereotypes. Worse yet, the story these characters pass along is not even their own, but viewed from a distance as the leaders of the field teams in biology and astronomy have a brief, ill-fated fling.

And that’s the whole story. Time travel, paleozoology, and astronomy play no real part in the tale, nor does any recognizable human emotion beyond jaded surprise and incredulity. “The Tortoise Grows Elate” is many thousands of words too long for what it delivers, but the frustration stems mostly from the sense, well founded, that Mr. Utley can do so much more with his prose. The writing is smooth enough, and the dialogue facile enough, that it leaves a strong willingness to find another story by this author, and give that a go. There is nothing wrong with trying, as the characters in this story learn, but, as they also learn, sometimes an attempt’s failure is sudden and comprehensive. As much as this story tries to do, it ends up burying significant skill in a heap of collapsed literary technique.