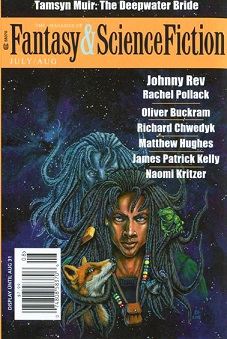

Fantasy and Science Fiction, July/August, 2015

“Johnny Rev” by Rachel Pollack

Reviewed by Martha Burns

Jack Shade makes a duplicate of himself so that he won’t have to personally interact with his mother-in-law. Who hasn’t been there? Unfortunately, Jack is having some difficulty getting rid of the duplicate, who would rather be the main Jack, not the extra Jack. Usually it isn’t so difficult to get rid of a duplicate and the mystery Jack must solve is why he’s having the problems he’s having and how, of course, to get rid of his duplicate. The thing is, the duplicate may have a point. He’s free of Jack’s tortured backstory that includes a dead wife and kidnapped daughter. In that sense, the duplicate might actually be Jack’s happier and better self. Of course, the duplicate wouldn’t have any reason to avenge the dead wife or to rescue the abducted daughter. The strength of the story lies in its world. “Johnny Rev” by Rachel Pollack is set in a multiply-layered world and although much is thrown at the reader—including the existence of a Sun King and a spirit fox familiar—the world is never confusing and each portion comes into play. The death of Jack’s wife and his relationship with his daughter is not, however, developed and because it is the event that shapes Jack’s character and explains his actions, it’s difficult to appreciate what is at stake for Jack (other than a very generic desire for revenge and rescue). The major complication, which involves a former girlfriend and her father, also doesn’t help one understand Jack in any greater depth. The expected comic riff on Jack’s problems with every in-law in his life doesn’t happen either. Jack does, however, move through a gripping world. Read it for the world, which I hope is used as a setting for other tales.

What makes young-adult fiction shine is the voice. YA with a strong and sassy first person teen voice gives us some of what P.G. Wodehouse gave us with Bertie Wooster’s zippy argot. Tamsyn Muir uses the voice to brilliant effect in “The Deepwater Bride,” in which Hester Blake, a sixteen-year-old seer in a family of seers, recounts her summer break with boring Aunt Mar. Hester uses her time with her aunt to read the family’s witchy journal, to figure out what’s going on with the deeply strange omens infecting the town, and to make a friend. It would be a first for Hester and the friend is an unlikely pal. The friend, Rainbow, is a popular girl who is into popular teen things and though Hester is more of a baby goth, Rainbow likes Hester and is plucky, unfazed, and fascinated by the town’s strange goings on. Far be it from Rainbow to be shocked at a shark in a tree. Then Hester figures out what’s going on in the town. All of the signs point to the dark lord’s search for a bride and Rainbow, sadly, is the bride. Can Hester save Rainbow? The ending of this treasure of a story is emotionally satisfying. Highly recommended.

In “The Body Pirate” by Van Aaron Hughes, insubstantial entities can inhabit human bodies and for generations they have been doing just that. The entities, who call themselves Blackbirds and use the plural in place of singular pronouns to refer to themselves, justify this relationship by viewing humans as empty shells. The civilization hails a new advance in which a single Blackbird can have multiple human bodies at their disposal, though this means that bodies without their hosts will exist as separate entities for much of the time. This advance causes obvious problems for a society that thinks of the humans as empty shells and the narrator, Adela, is forced to question the morality of what they’ve been doing, which isn’t to say Adela is especially clever or especially morally aware. That complexity sets the story apart and we feel Adela’s epiphany all the more. Some things, sadly, do get in the way. First of all, Hughes chooses a technique in which parallel columns show the experiences of Adela and one of their bodies, which is that of a human male. Overall, the technique works well, but when it is first introduced, it is unnecessarily jarring for the simple reason that we do not have Adela’s name and so, when the split happens for the first time, we don’t know who is being referred to. Since a name before the first split would have fixed that, it is an annoyance. Second, the plot device Hughes uses to cause Adela to wise up is not only cliché, but not a good fit. The twist involves sexual betrayal and the cruel heart of a woman (even if “she” is a gender-less entity who happens to be inhabiting a female host at the time). That plot reduces a genuine question about the morality of possessing humans to a sex scandal. Aside from the tiredness of this device, the sex scene, like many sex scenes, intends to be sexy and is not. What the sex scene achieves is more anatomical information than is helpful. Consider the following three descriptions: 1) the car won’t start, 2) the car’s alternator is shot, and 3) though the car’s pistons thudded on and on, no AC power shot through the machine and Faraday’s Law hung limp and unsatisfied. The final description has its place, surely, but those contexts are rare and if one gets that level of description in the wrong context, it will be either jarring or comic. Yet so much sex talk has the shape of that third sort of description when all we really need to know is that the car either won’t start or the alternator is shot. Therefore, despite the cleverness of the story and a degree of strength in characterization, Adela’s realization is undercut by decisions that do not, ultimately, serve the story well.

“The Curse Of The Myrmelon” is a one of a series of stories by Matthew Hughes. Collectively, they’re the Archonate stories and while all share a set of overlapping characters, the thing that ties them together is the peppy diction. Here, a detective who uses magic, Cascor the discriminator, gets a new case. A man shows up and says he’s been cursed by a magical being, but Cascor is not so sure the magical being in question is likely to try and drive someone crazy by fiddling with inventory control in their warehouse. To solve the problem, Cascor calls on Raffalon, the thief, and they uncover a conspiracy that is farther-reaching than how many items really are in row five. The story zips along, and while I didn’t care much about the conspiracy once it was revealed, the banter was delightful. Recommended.

Noami Kritzer‘s Seastead stories are set within a collection of large, floating homesteads off the California coast. Beck, a teenaged girl, had been living on one of the floating homesteads with her father until he and other scientist colleagues created a plague that I wish I had access too as it makes sufferers want to clean. Now that Beck’s father has left to avoid being put in prison, her mother travels to Seastead to reclaim her daughter and take her back to California. First, though, Beck has a final adventure in “The Silicone Curtain: A Seastead Story” to try and clear her father’s name (and the names of the rest of the scientists) and to, in addition, outwit her mother, who doesn’t realize just how brilliant Beck is. Beck is, indeed, brilliant and with the help of her sidekick, Thor, she saves the day for the scientists who created the plague and uncovers something far more sinister than a threat with jail time. The intricate backstory doesn’t clog things up as Kritzer gives us what we need to know without going into much detail, but the story also relies on the emotional connection the reader formed with Beck in previous adventures. I’d encountered Beck before and was satisfied by this adventure and left wanting more, but without knowing and caring about Beck from previous exposure where the focus was on her character first and plot second, I am not sure I would have enjoyed the story anywhere near as much. It’s hoped that interested readers seek out the other Seastead tales and it’s hoped that Kritzer collects those stories together soon. Recommended for lovers of the series.

In “Dixon’s Road” by Richard Chwedyk, the curator of a museum shows a visitor around. The museum is the former home of the poet Laura Michel and though the curator, Alice, shows the visitor the usual things such as the library, she focuses more intently on the love affair that defined the poet’s life even though the visitor seems to know all about it and is eerily familiar with the layout of the house. The focus of this tale, which is reminiscent of “Rip Van Winkle,” isn’t actually the visitor who returns home after a long trip in stasis, but the curator who has devoted her life to the museum. Who loves the writer more? Is it the reader or the actual lover? An easy move would be to make the reader into a shallow idolater, but that’s not who Alice is. The joy of the story is thinking about the relationship between writer, reader, history, and imagination. Recommended.

“Oneness: A Triptych” by James Patrick Kelly presents three short takes on sexuality. The first, and most successful, “Trick,” involves a heterosexual cisgender couple trying to spice things up on their anniversary. What is hilarious and entirely right is the way Kelly matches the sexuality, the spicy sex they choose, and the gender of the couple to their personalities. Who is a manly man and who is a womanly woman? “Trick” gives an amusing answer that felt so right. The second story, “Tryst,” again questions some of our assumptions about gender, but the insight passed me by, though the sex in question is enjoyable because it is so gross. The third story, “Test,” similarly baffled me. Some comment on overly-zealous church ladies seems intended, though I suspect it is something more than that even aliens find that group annoying. Although a mixed bag, “Trick” has genuine focus and wit.

“This Quintessence of Dust” by Oliver Buckram has a passing similarity with Ray Bradbury’s “There Will Come Soft Rains.” In both, after all of humanity is dead, the machines go on. Yet in Buckram’s story, the machines are not dignified roombas, they are the sensitive and caring and, most importantly, morally upright robots more from Isaac Asimov’s world than Bradbury’s. With those two considerations together, the question is, What is a carer to do when there is no one left to care for? The answer is that there is always someone to care for. That realization is captured with skill in this story that is simple on the surface, but not simplistic in the least. This one will stick with me. Recommended.

In “Paradise and Trout” by Betsy James, Hally Kass has recently died and, as he walks from the land of the living to the afterworld, he must decide whether or not to take his father’s advice. Hally’s father, who can communicate with the dead, gives Hally explicit instructions—talk to no one on your journey, they are all demons. This is not Hally’s experience and, during his final journey, he has to do what all of us have to do in life, which is distinguish ourselves from our parents’ worldview. This is, therefore, a coming-of-age story, though within that simple structure James manages to successfully pull something off that is more generally groan-worthy. James offers a meditation on both nature and death in which nature is neither Eden nor a savage place and death is neither a release from the Hell of living nor a torment. This well-crafted story rewards rereading. Recommended.

Franden’s job is not only to escort a media mogul around Zephyr; it is to single-handedly save his adopted home. Zephyr is a backwater moon and might be closed down unless someone can show the intergalactic public that Zephyr is hip, hot, and happening. Franden, a hitherto unpublished writer, is as close to a savior as Zephyr is likely to get if, that is, he can craft the right video. No pressure. How he does this is brilliant, funny, and will satisfy any science buff who has ever wanted to scream at a New Ager that cleanses are absurd because humans come complete with livers, kidneys, and intestines. Gregor Hartman‘s “Into the Fiery Planet” is delightful and highly recommended.