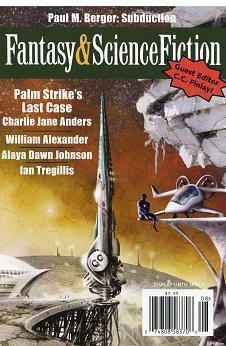

Fantasy & Science Fiction, July/August 2014

Fantasy & Science Fiction, July/August 2014

Special Guest Editor: C. C. Finlay

Reviewed by C.D. Lewis

This issue of Fantasy & Science Fiction presents thirteen original stories from authors Fantasy & Science Fiction has never previously published. That’s not to say the authors are all new to print, or that you won’t recognize some names from their awards, but they’ve never previously been in F&SF. The stories range from comedy to horror, the subjects range from superhero tales to normals escaping by the skin of their teeth, and the settings range from the age of sail through the current time to laboratories orbiting distant worlds. This issue’s got something for everyone.

In language recalling a noir’s narrative overdub, Charlie Jane Anders’ “Palm Strike’s Last Case” delivers a de-glamorized look at an ageing superhero with little left to rescue. Anders introduces the protagonist lugging his heavy equipment across town, felling evildoers and interrogating minions, stubbornly plunging forward despite accumulating injuries. Instead of swelling with can-do, though, Palm Strike heaps criticism on himself for every failure: duty won’t let him quit, or his need for vengeance, but he’s been so hollowed out by the world’s oppressions and his own losses that there’s little heart left in his fight. He’s just too stubborn to quit. When the letter arrives accepting his mild-mannered alter-ego into the off-world colonization program, he rankles against the ticket out of his crumbling city: his nemesis remains. But the collapsing criminal empire suggests his nemesis may be leaving, too…. “Palm Strike’s Last Case” shows a bitter vigilante transformed by new purpose, and the refreshing power of an innocent’s genuine belief. It’s a superhero romp crossed with a dystopic future on an isolated colony where corrupted government and poisoned earth threaten a whole community’s very survival. This mashup is worth the read.

Hunted by foes he’s forgotten, the protagonist of “Subduction” employs barely-remembered skills to survive while longing to remember who he really is. This may sound like the open to Ludlum’s The Bourne Identity or Zelazny’s Chronicles of Amber, but there’s a reason writers mine this shaft: for the right miner, it’s got a gold vein a mile wide. Paul M. Berger’s “Subduction” opens on the protagonist discovering a weird corpse, whose native habitat he knows despite a frustrating fog of lost recollection. Unlike Zelazny’s Corwin or Ludlum’s Bourne/Delta, “Subduction”’s protagonist doesn’t struggle to piece himself together from clues; the fragments of memory he gets tease that he’s more than he appears, but he remains oblivious until – properly triggered – he recalls it all. The climax of “Subduction” isn’t a hard choice, but a reveal: what the protagonist is, how he lost his memory, and why he willingly dooms himself to sacrifice it again. Substituting the reveal for a hard choice might not work for a longer tale, but it feels a fitting step in the reversal-rich sequence Burger lays out in “Subduction.”

Annalee Flower Horne entertainingly presents “Seven Things Cadet Blanchard Learned from the Trade Summit Incident” as the essay component to a trainee’s disciplinary action. The essay’s smartass tone provides this reviewer a pleasant reminder of the tone taken by this reviewer when assigned essays as discipline – though, naturally not for allegedly delaying orbital trade talks with stinkbombs. The fact this elicits fond memories in the reviewer raises hope that it strikes a similar chord with snarky nerds everywhere, and those who love them. I harp on this tone because it is a major selling feature, underpinning a narrative voice that elicits a wry smile as Horne’s protagonist interrupts her narrative to deliver the lessons she purports to have learned. The structure creates wonderful anticipation: as the narrator exonerates herself from accusation after accusation and proves herself justified in everything she’s actually caught doing, the reader wonders just what she is busted doing to receive the discipline that invited the essay. Although a science fiction story in its props and setting, “Seven Things Cadet Blanchard Learned from the Trade Summit Incident” is a comedy – and a work of comic genius. At less than three thousand words, you can’t justify not reading it. So, put this down now, and do it. I’ll wait.

“The Traveling Salesman Solution” by David Erik Nelson features a wheelchair-bound war vet whose computer expertise suits him to unraveling the mystery behind his brother-in-law’s inability to explain apparent defeat by a cheating marathoner. Nelson presents an entertaining problem: How does a marathon cheat beat RFID tag mats placed on the race course? How does he get his photo in the right place in the race promoter’s own photos? More than that question, Nelson presents its investigator: a man with a wheelchair chafing under the alternating glares and helping hands of those nearby when he visits relatives for dinner or travels by airplane. The narrator’s perspective features prominently when he discovers the root of the mystery involves strangers who’ve revolutionized the solution to a complex math problem: he regards this as more dangerous than being able to teleport explosives into government buildings. As a programmer, he understands how revolutionizing complex math with cheap tools affects computer security, international finance, and everyone’s life savings. Several pages are invested explaining that wide availability of security-cracking math is an international disaster that will cost lives, so even readers who don’t understand the math will follow through analogies. The narrator compares his dark choice with that of drone operators, who dispatch dangerous bomb-makers in their homes by remote even when they spot a tricycle outside. The protagonist brings the story’s focus from the damage risked by one madman to the broad principle that violence solves problems, and shows the personal cost of the choice his conviction drives him to make. It’s a dark story, and gets high marks for provoking thought.

Sandra McDonald’s “End of the World Community College” is a humorous piece that presents itself as a college handbook and course catalog. The school’s post-apocalyptic barter-style tuition suits the school’s theme, as does its application process. Course descriptions offer an entertaining window into the ruined world for which the EWCC prepares its students. “End of the World Community College” feels strengthened by the author’s employment of Write What You Know, through which McDonald leverages community college teaching experience to lampoon both higher ed institutions and their student bodies. And – what with the zombie plague and the trigger-happy registrar – perhaps also students’ bodies. McDonald’s farce setting should entertain anyone, but her jokes targeting the administration will be especially appreciated by those who’ve been near higher education.

Set in a fantasy version of South Africa, Cat Hellisen’s “The Girls Who Go Below” follows English sisters summering at their aunt’s lake home when they meet a boy. Not a wholly human boy, as it turns out. The boy fuels escalating tension between the narrator and her sister. When the boy, who makes violins, offers to show the narrator how he does it, the tale takes a turn for the darker. Throughout, Hellisen builds a creepy, dark mood. The sisters’ disintegrating relationship raises a disconcerting feeling: differing views on the boy and secrets between the sisters raise anticipation of disaster that fertilizes the horror so suited to the story’s conclusion. Readers who want to understand characters’ decisions may feel frustrated: is the narrator’s dark choice really explained by the dizziness of a mortal mind in love? Does one sister simply grow to loathe the other? Do we believe the boy’s charmed the sisters since he met them, robbing them of free will? Although the tale offers pleasantly dark imagery and an excellent discomforting horror vibe, it manages to leave unexplained the dark choice that’s at the core of the story’s resolution. Readers who like creepy, weird, dark tales will enjoy the journey.

Sarina Dorie’s “The Day of the Nuptial Flight” explores aloneness in crowds, social ostracization, and sexual identity through a beelike alien’s narration of his introduction to humans. When presented an opportunity with a queen in a mating frenzy, he discovers to his shock and shame that his body doesn’t do what he or the queen or the other males expect. Rejected by his own kind, he becomes enamored of a passing human woman. The insectoid narrator’s xenophilic interest in pregnant humans may not be for every reader. The narrator’s sexual behavior lies beyond his control, driven by chemical signals and cues he does not fully understand and over which his will exerts no influence. Even more stressfully, when he tries to interact sexually he’s not seen as “normal.” The narrator’s quixotic quest to be accepted by someone he regards as a “queen” – so that he can proceed with his transformation into an infant-rearing “handmaiden” – provides the primary story arc.

The narrator’s sexuality is not mere window-dressing, though: the narrator’s expectation he could plausibly mate with the first woman he sees offers a first glimpse into just how out of touch he is with humans – while beginning to illustrate how oblivious humans are to everything the narrator thinks, feels, and knows. Just as the narrator can’t imagine that human responses to his ritualized interactions have meanings other than those ascribed to them in his own hive, humans are unable to understand what the narrator knows about his world and its natural-medicine remedies to problems that include the humans’ inability to raise children on the planet. Once the narrator learns enough to communicate, humans remain slow to believe him. The narrator’s perseverance transforms him. Although the story opens on a chemically-driven mating machine who’s desperate to mount any queen who’ll have him, he becomes a selective protector of one chosen human who’s learned to appreciate his virtues – though she remains apparently oblivious to his sexual interest. The narrator’s rocky road full of setbacks, misunderstandings, and a depressed certainty that he has failed all build to a … well, climax. And perseverance produces results. The conclusion suggests hope for outcasts who don’t fit in – even when confronted by socially-conforming adversaries who blend effortlessly into society, and seem to hold all the cards.

Dinesh Rao’s “The Aerophone” opens on a man disappointed to go on a trip because he enjoys the sedentary life that followed his motorcycle accident. The tale’s initial motion stalls amidst heavy exposition delivered through mealtime conversation. Once the main character gets his hands on the instrument that gives the story its name, the horror begins to unfold: the Aerophone of Death, once used by initiated Aztec priests with special training in death rituals, yields visions and messages from another realm. Despite his misgivings about continuing with the sessions encouraged by the instrument’s owner, the main character offers little resistance to his acquaintance’s scheme to expose him to the seemingly hazardous tool for “research.” The horror vibe is best while it’s unclear whether the main character is helping aliens escape oppression, or being conned into opening a gateway to an invasion of Earth.

Unfortunately, the Aerophone of Death doesn’t seem to live up to its name. The worst thing it inspires seems to be a spate of angry answering machine messages left by a graduate student upset over an interrupted thesis. The discoveries made by the main character have a feeling of occurring by chance, rather than appearing the result of hard choices that reveal personality or values. When his research gets funded without apparent effort, his decision to accept the funding isn’t hard because he doesn’t believe there’s a risk. This might build to a horrific reveal, but the horror elements’ anticipation don’t deliver on their creepy promise or deliver an awful climax. Although horror tales sometimes offer little change besides the observer’s realization of some awful truth, “The Aerophone” doesn’t deliver horror. Since the main character never confronts the hard choice that reveals and sells a character’s change, “The Aerophone” doesn’t give the feeling of a story arc. Instead, it sketches a world in which aliens use a wind instrument to steer humans to open a portal for their arrival, without showing why this matters. The conclusion gives every impression the main character’s action is akin to stopping charitably to help a stranger change a tire: there may be risk, but the curtain closes before it can be realized. Even a great backdrop needs a story.

Ian Tregillis’ “Testimony of Samuel Frobisher Regarding Events upon His Majesty’s Ship Confidence, 14–22 June, 1818, with Diagrams” follows the testimony of a man press-ganged into the Royal Navy and made witness to the fantastic horrors that befell the ship and its captain. Deafened by a naval gun mishap, the narrator alone avoids charm by the siren spell woven about the crew and captain by the Tentacled Bride. The narrator recounts the last voyage of the Confidence and the particulars how all other hands were charmed into servitude. The tentacular horrors and the narrator’s helplessness will appeal to Lovecraft fans. Some readers demand a protagonist who does more than escape with his life, but this story is not for them. Those who like a narrator who keeps his head long enough to report the doom that awaits the Empire on the high seas, and who thrill at the likelihood the court’s presiding officers will ignore the last warning they’ll get before the end comes for them in the dark of night from the depths of their harbors and river docks, will find Tregillis’ tale a perfect fit.

Spencer Ellsworth’s “Five Tales of the Aquaduct” connects five vignettes by their connection to a canal in southern California – or where the canal will be in tens of millions of years when humans appear to build it, or where the canal had been tens of thousands of years ago before tentacled alien explorers crashed in the desert that had been California. Facts are not related in linear time, and they reveal no over-arcing plot: it is an anti-story. Like an absurdist Python skit, it succeeds only if it entertains with its ironic juxtapositions and/or humor.

Haddayr Copley-Woods’s “Belly” is a coming-of-age story set within a community of monstrous cannibal witches. It’s also an allegory about overcoming abuse, mistreatment, and family expectations to become a decent person. Although much of “Belly” follows a girl dragged, resisting, into a cycle of abuse, the narrator is initially unable to resist becoming her abuser but finds insight, and ultimately finds the strength to turn aside from perpetuating the cycle. By depicting the parade of awful trials in a matter-of-fact tone but raising the act to resist her family’s pattern as requiring all her strength, “Belly” renders heroic the narrator’s refusal to indulge her awful impulses.

William Alexander opens “The Only Known Law” in a laboratory orbiting a distant world where a married couple of academics attempt communication with a recently-arrived alien messenger. The alien’s uncommunicativeness frustrates diplomats, but when it develops the ability to speak it so enjoys conversation with the couple that it delays giving the message the delivery of which will complete its purpose and initiate its destruction. Alas, the message proves time-sensitive. This isn’t a story that includes an alien solely to push it into the science-fiction genre, it’s a tale whose offworld setting and futuristic ailments are crucial to the plot. “The Only Known Law” not only says something about the relationship between man and technology, but something about people and love and communication. Alexander’s tale is a short delight.

In Alaya Dawn Johnson’s “A Guide to the Fruits of Hawai’i” a horror world overrun by vampires is revealed through the eyes of an ageing human enamored with a vampire she declined to kill before the war was lost. Promoted from monitoring a blood-donor concentration camp to managing a luxury feeding center, the protagonist has enough humanity to recognize the horror about her but lacks the strength to fight it. Driven by her own affections, fears, and ambitions, she assists the vampires as a human collaborator. “A Guide to the Fruits of Hawai’i” sympathetically portrays the evils humans can commit while looking out for themselves, and illustrates that love need not be noble or kind but can be selfish and a compass to one’s own destruction. Perhaps the richest horror aspect is the protagonist’s decision to resist – a decision made too late to matter.