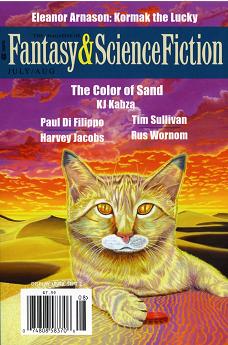

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, July/August 2013

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, July/August 2013

“The Color of Sand” by KJ Kabza

“Oh Give Me a Home” by Adam Rakunas

“Half a Conversation, Overheard While Inside an Enormous Sentient Slug” by Oliver Buckram

“The Year of the Rat” by Chen Qiufan

“Kormak the Lucky” by Eleanor Arnason

“The Woman Who Married the Snow” by Ken Altabef

“The Miracle Cure” by Harvey Jacobs

“The Heartsmith’s Daughters” by Harry R. Campion

“The Nambu Egg” by Tim Sullivan

“In the Mountains of Frozen Fire by Denis Winslow Codswallop Bourginon Cushing” by Rus Wornom

Reviewed by Colleen Chen

I always have high expectations when reading F&SF, but I found this issue particularly delightful. Much of it read like a selection of folk and fairy tales, complete with talking animals and legendary folk, interspersed with a couple of science fiction stories and a dash of horror for variety.

“The Color of Sand” by KJ Kabza is a whimsical tale of a five-year-old boy named Catch who lives on the edge of the dunes with his mother and his only neighbor, a talking sandcat named Bone. Catch and his mother, who pick up mysterious colorful pebble-like objects on the beach to trade and sell, discover one day that the objects, called refulgium, are magic. Catch swallows a red one and becomes a giant. Guided by Bone, he and his mother embark on a journey along the coast to the perilous Final Atoll to seek a black refulgium that will return him to normal size.

This story was such a pleasure to read. It’s smart and funny enough to appeal to adults but would also enrapture children of any age. All the characters are lovable, even the ones who aren’t so nice. There’s a nice theme of the consequences of rash behavior in this tale and some other levels of symbolism if someone happened to feel the urge to delve deeper into it.

“Oh Give Me a Home” by Adam Rakunas takes place in a future in which a Monsanto-like entity called Amagco has achieved its goal of near-total control of agriculture and meat production. The narrator is Brew, who has avoided using Amagco-mandated fertilizer and modified feed by genetically modifying heritage bison until they are small enough to need very little space. The story begins with Brew being sued by Amagco, who is trying to stop him from producing bison so it can kill off all heritage breeds and strengthen its monopoly on the market.

Brew fights Amagco’s taking his cattle for incineration, his feelings of betrayal by an old friend who now works for Amagco against him, and an overwhelming feeling of the inexorable march of progress.

This is a true David and Goliath story, and quite an enjoyable read—entertaining and funny even as it deals with a serious and socially pertinent issue. It shows that there are always loopholes to what may seem like a no-win situation, and this message in the ending, the note of hope and signs of a battle won if not a war, made it particularly satisfying.

“Half a Conversation, Overheard While Inside an Enormous Sentient Slug” by Oliver Buckram is one of the oddest but most delightful short mystery stories I’ve ever encountered. It’s exactly as the title says; we hear only the voice of a sentient slug. As a servant of the late Lord Ash, he is being interviewed by an inspector investigating Lord Ash’s murder. The slug isn’t sorry about the murder, as Ash was a cruel and capricious master, who, for instance, liked to spill salt on the slug and laugh. On the other hand, the murderess, Lord Ash’s wife, was kind to the slug—so it’s ironic how cooperative the slug is in explaining her culpability to the inspector. Or is it?

This tale, unique in both plot and style, had me chuckling throughout. It’s very short but works well.

“The Year of the Rat” by Chen Qiufan (translated by Ken Liu) follows the futuristic story of an unemployed recent graduate hired to join the Rodent-Control Force, which hunts intelligent mutant rats infesting the Chinese countryside. The platoon is a mixed group—on one end of the range is the narrator’s friend Pea, who feels sorry for the rats and can’t bear killing them, and on the other end is Black Cannon, whose quota of killed rats is always the highest. As the group struggles to help control the infestation, they discover that the rats are evolving rapidly—for instance, learning how to overcome limitations in their genetic programming and having the males become pregnant. At the same time, the narrator has even more disturbing realizations about the nature of the war he’s fighting.

This is a dark and brilliant story, at times disturbing and at times gruesome. There’s no telltale awkwardness in the language that reveals that it is a translation. The story captures the mentality of students in an unwelcoming economy perfectly, the futility of war and its service only to the machinations of a few. The stripping of humanity amongst the pawns of war is revealed starkly by the narrator’s emotional reactions, particularly in his attempt to mourn his dead friend. I even feel sorry for the rats here, who are just as much pawns as the unfortunate members of the Rodent Control Force. Good story!

“Kormak the Lucky” by Eleanor Arnason is the tale of an Irish man who becomes a slave in Iceland. Sold to one farmstead after another, he ends up at the mercy of a powerful Viking who, although old, still wields magic. When the old man tries to kill Kormak for witnessing him getting rid of some chests of silver, Kormak escapes through a door to the land of the elves—and finds himself enslaved yet again. He finally gets a chance to escape when the beautiful daughter of an elf-lord wants to go to the land of the fey in Ireland, where she says she’ll set him free—but then she doesn’t.

The story reads just like a fairy tale, one of those authentic, non-Disney kinds that is slightly disappointing because it emphasizes learning a lesson rather than a happy ending or heroic deeds. Kormak (who I didn’t really see as being lucky in any way) seems rather passive, taking action only when he has no other choices. The characters are fairy tale characters, more archetypical than deep, and not particularly likable. The story is interesting, however, for its cultural flavor, its message of how “there is more than one kind of slavery,” and how it realistically portrays how otherworld beings would act if they did exist. Its ending is bittersweet, offering a more realistic portrayal of human behavior and emotional reactions rather than giving us a happily ever after.

“The Woman Who Married the Snow” by Ken Altabef describes one of the more eventful days in the life of the shaman Ulruk. Members of his tribe discover the body of a man named Toonookyah, lost five winters ago, frozen in the lake water. The grief of Toonookyah’s widow is renewed at the sight of her dead husband, and she begs Ulruk to do something. Moved to compassion, Ulruk thinks to give her closure with her husband by calling the spirit of the snow to help. Toonookyah animates, but not with his long-gone spirit—with the spirit of the snow, and with all the attendant emotions of snow—meaning, none at all.

This is a rich, atmospheric tale of the interaction of spirits amongst both living and dead. It’s also a story of the consequences of unintelligent choices. I appreciated the writer’s impeccable voice and the glimpse into a tribal culture, but felt indifferent about the characters and the story itself—I’m pretty sure this is a matter of personal preference, though.

In “The Miracle Cure” by Harvey Jacobs, unexplained miracles are taking place in medical clinics all over the world—people’s gallstones are disappearing the night before gallbladder surgery. Although most of the doctors scoff at the idea of miracles, Dr. Chalmers believes something weird is going on, and she’s determined to get to the bottom of it. Nights of trying to stay awake watching a patient the night before a gallbladder surgery reveal nothing—until one fateful night, when Dr. Chalmers meets an unexpected visitor to the surgical table, someone who takes her on an amazing and view-expanding journey of explanation.

This rather silly, light-hearted story is entertaining, albeit at times a little bit gross. This sort of humor so often falls flat for the unprepared reader, but in this case it’s done quite well. Not to be analyzed beyond face value, the story is good for a few laughs.

“The Heartsmith’s Daughters,” by Harry R. Campion, is another story with the flavor of a folk or fairy tale. A dying blacksmith who had promised his wife after miscarrying that they would have more children uses his last strength to forge three magical daughters. One has a heart of iron so she can protect her mother, one has a heart of brass so she can carry on the blacksmith business and support her mother, and one has a heart of gold, to give her mother love. But the daughters face a terrible test when five ruffians covet the blacksmith’s tools. They are turned away easily enough by Ironheart, beaten and turned into town laughingstocks, but they become ever more dangerous in their humiliation, and they plan revenge.

This is a story of the destruction of innocence and the power of love to heal—although it also has a moral, that love can’t heal a heart back to a state of innocence. It’s a beautifully told story, simple but with layers of metaphor, and it made me wish I could read a full-length novel with the stories of these daughters, who are all powerful but highly flawed—the weakness of each is in their existing in separate bodies.

In “The Nambu Egg” by Tim Sullivan, Adam Naraya has been living for many years as a civil servant on Cet Four, a heavy-gravity planet on which poor people from Earth can go to try to start a new life. He goes through the process of death and reassimulation—which is how people travel far distances in this future—in order to visit Earth to allegedly sell a Nambu egg. This egg is a mysterious and powerful object that comes only from Cet Four, and he offers it to a wealthy man named Hamid Ganzler. It turns out that the egg is simply bait—he wants to mitigate his guilt about a woman’s death by discovering who was responsible for putting her on Cet Four as a convict.

This story feels like it just touches the surface of a much larger story. Too many characters, too much world was introduced with no time to develop it, so we got a slice of life in this world but not enough to understand or really care about the characters. The bulk of the story is a dialogue between Naraya and Genzler, and I didn’t really see the point of all that talking. Intriguing story, but unsatisfying as a piece in itself.

“In the Mountains of Frozen Fire by Denis Winslow Codswallop Bourginon Cushing” by Rus Wornom is a Lovecraftian tale of an adventure involving the amazing secret operative M4. We’re thrown right into the action as M4 battles three foreign brigands who try to thwart him on his search for his nemesis, an agent called the Cobra. Brilliant as well as skilled in martial arts, M4 follows the Cobra’s trail to the cold and mountainous country of Ghutran, where he finds a guide to lead him into the Wastes, where lie the Mountains of Frozen Fire. Battling numerous obstacles into the Mountains, M4 meets not only his nemesis but a horrific otherworldly enemy that threatens to take not only his life, but his sanity as well.

I enjoyed this story from start to finish—the satire of the secret agent mission is taken to new heights of hilarity here. Each character has his own highly developed caricature of a background and it’s all done very well. Even the length of the story isn’t off-putting, as the story has enough twists to keep the readers’ interest.