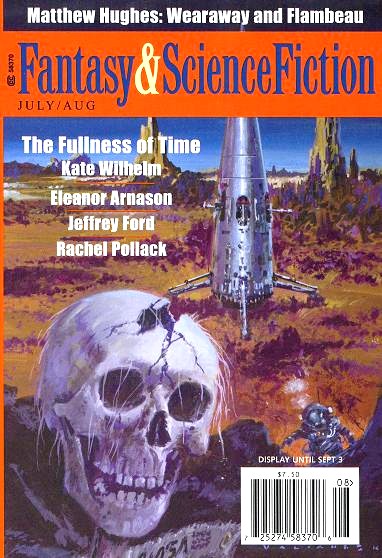

Fantasy and Science Fiction, July/August 2012

Fantasy and Science Fiction, July/August 2012“The Woman Who Fooled Death Five Times” by Eleanor Arnason

“Wizard” by Michaele Jordan

“Jack Shade in the Forest of Souls” by Rachel Pollack

“The Afflicted” by Matthew Johnson

“Real Faces” by Ken Liu

“Wearaway and Flambeau” by Matthew Hughes

“Hartmut’s World” by Albert E. Cowdrey

“A Natural History of Autumn” by Jeffrey Ford

Reviewed by Robert Brown

Eleanor Arnason “The Woman Who Fooled Death Five Times”

A story set among ET furries on a distant planet, part of the long-running hwarhath series. In this folktale retold by a human researcher/xenologist, with notes appended, a strange woman who really doesn’t want to die plays a game of survival with a dull-witted and winsome personification of death. It’s an odd story, playful and somber, the point of which is: you can’t cheat death. You’re wiser by far to accept death’s inevitability and go forth and be a kind, generous person so that such riches as the world can offer will be yours, and your soul shall be unencumbered, etc. and so forth.

What we have is an ethnographic datum of a people who do not exist. A story set among a fanciful species drawn from the imagination of a human being. A fable with a moral never passed from anyone to anyone, solely the product of a single person—Eleanor Arnason—making it all up. If all these hwarhath stories were collected together, the whole would produce an interesting mosaic portrait of a possible ET species. All by itself, the present story is witty and charming, a pleasant enough diversion to while-away an hour before death comes knocking on your door.

Kate Wilhelm “The Fullness of Time”

Given the author’s previous work and the title, you’d expect a time-paradox story, and you would get one, though you might be disappointed on that count. The focus here is more on the nefarious schemes of the “mad scientist” who hopes to exploit the hapless time-loosened family members she is ostensibly charged with treating for a rare form of narcolepsy than it is with the intricacies of time paradoxes or the mechanics of time travel. There’s a bit about how awful it is to live unhinged in time, and it has wrecked several generations of the family, but that material is ancillary to the looming threat of a breeding and training program to produce a team of mutant time-hoppers.

It’s an old-fashioned paranormal investigation story, though in this instance the investigatory team is a professional researcher, and a film crew shooting a documentary about an extraordinary father and son who, before their deaths, displayed an uncanny ability to anticipate the future, and profited plentifully thereby. The story comes complete with gothic scenery, family secrets, tech whiz assistants, dramatic confrontations, and insidious evil. It reads a bit like a teleplay, and could serve as the platform for a solid teevee episode (of some sort).

My only reservation regarding the story is the portrayal of the alcoholic father of one of the “patients.” In my own experience, alcoholics rarely muster to reveille and charge to the rescue. I suppose the redemption of a loving father is sweet, but it rang false for me. Wilhelm has more optimism than I have.

Michaele Jordan “Wizard”

Girl meets boy (man), girl abandons home and former life to live in closet with man, learning to read Japanese poetry, and delivering lectures on Hebrew cantoring. Vague breakthroughs are achieved.

This is a quirky story, and unique, but the underpinning is absent. Nothing much is explained, by which I do not mean the magical system, which—sketchy though the explanations are—is carefully implied (I quite liked the spell-casting use of the haiku), so much as I mean the character motivations. Why does the girl abandon her life? Why does the man accept her into his cloistered hermitage? How can the man slip through the centuries in passe duds yet use computers and credit cards? No doubt you might answer my objections with a grand “It’s magic, dummy!” but I consider such a response a facile evasion: the truth is this story makes no sense.

So, briefly: it’s interesting, and there is a story in this material, but this is not that story.

Rachel Pollack “Jack Shade in the Forest of Souls”

Jack is a “traveler,” a magical agent who can pass between realities to guide forlorn souls on their way to their destination, complete with animal companion and a mean way with a stick of chalk or a sharp blade. In this story he finds himself unexpectedly caught up in someone else’s designs.

Pollack describes a world of caprice and whimsy, a pernicious realm of perilous charms. A place where vows are literal and actions have consequences beyond the fields we know. There are rules governing, and reasons behind, everything that happens, but those rules and reasons are not always known, or even knowable. The details are convincing here: throwaway references to things such as “predator chickens” establish this realm’s bona fides; with less skill such details feel tacked on and phony, but Pollack is a magician and they are woven together to make a net of words which first dazzle and delight and then ensnare the reader, which is of course the oft-forgotten goal of the story-teller. Ensorcel me, please.

The ending sets up a series, which is de rigeur with this sort of story, and that’s fine, but it adds nothing to the story at hand. It’s a matter of taste, but if it were up to me, I’d have cut it and saved it for another installment. Here it feels shoehorned in, and to no particular narrative purpose or aesthetic gain.

Matthew Johnson “The Afflicted”

Really? Another bleepity zombie story? It’s a fresh take, I guess—if “fresh” and “zombie” can go together in the same thought—and the narrative is swift, convincing and involving. There’s certainly room in our collective library for an allegory which exploits the zombie trope to illustrate the trans-generational anxiety of resource-depletion our global society faces today, though I hasten to add that, while this story seems at moments to want to make that grab for pertinence, Johnson has not produced that allegory.

What we have instead is a taut and gripping thriller which follows the experience of a nurse in a national park, caring for the elderly victims of a plague which will eventually cause them to become zombies, herself a potential zombie. We don’t learn much, but the story is quite well executed.

Ken Liu “Real Faces”

A pertinent piece of sfnal extrapolation, based on the idea that someone will develop a masking technology which enables people to either completely obscure their physical attributes or mimic the attributes of another identity, whether gender, race or other. The hope is that this technological breakthrough will help resolve our persistent problems with racism and discrimination in the workplace, and in society in general. Of course, it doesn’t work out that way.

The narrative itself feels disembodied, as though Alice and Will are floating above the world around them, pontificating, discoursing, posturing, which I found pleasantly resonant with the story’s themes. There are playful moments here in addition to the food for thought. The moment when Will turns Alice’s heartfelt, though patronizing, sympathy into a racist faux pas reminds the reader how treacherous our social milieu has become of late, how easily one can slide from the enlightened side of the argument to the offensive, how readily someone can infer bigoted innuendo from ostensibly innocuous speech.

Liu takes up the phildickian bailiwick of authenticity here. Not so much “What is real?” which has become a bit of a tired sophomoric exercise since the post-modernist heyday, but “Who is authentic?” Even when dealing with terms which are easily definable, such as Estonian civil servant file clerks, there can be ambiguities and nuances which defy easy descriptions. Peril awaits the person trying to discern the pure member of a canard such as race. Is there an “authentic” “black” experience? Can there be such a thing? Liu offers no reassuring verities to guide us through this existential quagmire, he only lights the path a bit, allowing us to comprehend a bit more of the extent of the pernicious entanglements ahead.

Matthew Hughes “Wearaway and Flambeau”

A bit of sword-and-sorcery, featuring a character likely to become the star of a series of similar tales, a clever thief named Raffalon. Most of Hughes’ stories are set in what he considers Jack Vance territory, but this one feels more like Leiber (the language has a Vancian brogue): nothing wrong with that.

Fun, with a classic ending.

Albert E. Cowdrey “Hartmut’s World”

A couple of paranormal investigators are sent by a mafioso to expunge a ghostly vampire from the Balkan castle he has bought and placed in the Rockies as part of his ski resort.

Played for laughs, the main attraction of the story is the portrait of people from an earlier era, the assumptions they make, the way they conduct their affairs, and their treatment of other people.

This story didn’t do much for me at all. The bulk of it is a summary of a fanciful wikipedia article, and the interminable diatribes of an extremely stereotypical New Jersey guy.

Jeffrey Ford “A Natural History of Autumn”

A man meets an intriguing prostitute and they head into the mountains to gather material for a book she says she is writing about Autumn. Set in Japan, Ford explains none of the Japanese cultural material, allowing the reader to choose to get by on contextual inference, or do some googling—or just tread water. The idyll turns nightmarish, and the couple find themselves in a surreal, visceral night-time chase.

Ford’s work always reminds me why I committed fiction myself. He is an elegant, seemingly effortless stylist and this story has many poignant and chilling touches. The story is very Nipponese, especially the ending.