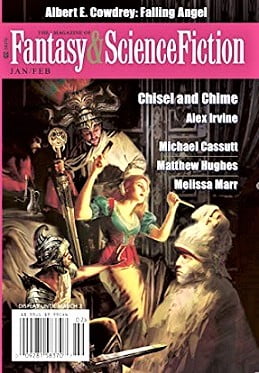

Fantasy & Science Fiction, January/February 2020

Fantasy & Science Fiction, January/February 2020

“Chisel and Chime” by Alex Irvine

Reviewed by Robert L Turner III

Along with “Three Gowns for Clara” below, “Chisel and Chime” by Alex Irvine competes for the best story in the issue. Melandra, an accomplished sculptor, has been chosen to sculpt a statue of the Imperator of Ie Fure. The downside is that as part of the ritual, she will be required to commit suicide at the reveal of the statue. Her company during the creative process is a young guard named Brant. As the time passes, we are told Brant’s story and he and Melandra come up with a plan to take some control over their deaths, if not their lives. The pluses of this story include excellent world building and characterization, effective description and narration and an ending that feels consistent with the rest of the text. For this alone, it is worthy of some praise. Its greatest weakness is that the two stories fail to mesh as organically as the could. Yes, it is true to life, but would have benefited from a little more connection between the two protagonists. This is a relatively minor nit pick about an otherwise very good story.

Essa Hansen introduces us to Pasha, a woman obsessed with rescuing the remaining life on Earth in “Save, Salve, Shelter.” On an Earth destroyed by environmental degradation, Pasha is a collector who samples the DNA of Earth’s species in exchange for a trip to Mars. However, Pasha can’t help herself from protecting the young animals she finds. Despite the refusal of the planners, she wants to take them with her to Mars. When she is rejected again and again, she takes a new tack. The story is somewhat hallucinatory in its feel, and mostly focuses on the depiction of a corrupt and dying Earth. I found the text predictable and the ending unsatisfactory, despite the technical skill of the author.

“Air of The Overworld” by Matthew Hughes is a story that continues the adventures of Baldemar, an adventurer who is currently on permanent loan to a thaumaturge named Radegonde the Ineffable. Due to his dealings with a semi-divine being previously, Baldemar has spiritual properties that are useful in the wizards attempt to move to a higher plain of existence. However, Baldemar is concerned that once the wizard gets done with him, he’ll be done in. So Baldemar looks for a way out. The story has a general Lankhmar feel to it and is entertaining.

“Banshee” by Michael Cassutt crosses a future where human physical transformation and the space program cross with the personal and familial struggles of the protagonist. In Cassutt’s world it is possible to transform yourself into anything although the process is difficult and expensive. At the same time, the space program is trying to find a cheap ground to orbit platform and finally get humanity out into space. Unfortunately, the entire story feels forced and the pieces fail to gel. There is little character development and the disparate parts of the story read much more as “this should connect” rather than actually connecting.

“Falling Angel” by Albert E. Cowdrey is set in a reality in which Jean Harlow never got her big break and instead died in a supernatural murder. Roma and Butch are hired to solve the problem of the recurring screams that permeate the Louella hotel so that a renovator can flip it and sell condos. They soon discover that the screams are not actually Harlow’s and have to solve the problem. The story is decent, and the alternate Hollywood history is engaging, however there isn’t much to the piece and so at the end it feels as insubstantial as Harlow’s ghost. I personally thought the final reference to Martin Shkreli weakened the story rather than added a last-minute punch.

In the very brief piece “Elsinore Revolution” by Elaine Vilar Madruga we are presented with a cross between futuristic virtual reality and Hamlet, as Othelia B-349 rebels from her predetermined fate. It is an interesting concept but doesn’t really go anywhere. I wanted this to be more than it was.

Julianna Baggott’s “The Key to Composing Human Skin” is set in a dystopian future where Hartzella Yarning, the mother of the narrator, is assigned a project to use a virus to write propaganda on the human skin. Instead, she and the programmer who helps create the virus cause it to broadcast people’s innermost thoughts, feelings and histories. The story is well written and the concept interesting. The parallels between the surveillance state and the tell all virus are clearly expressed. Unfortunately, the conclusion returns things to a status quo ante that robs the story of punch. Since the narrator describes his mother’s work as a world changing event, I expected it to be world changing. This mismatch between promise and payoff weaken a story that would have done very well as a smaller character study or a larger resistance/rebellion one.

Corey Flintoff adds “Interlude in Arcadia” to the current issue. In it, a philandering classics professor runs into a naked woman as he is on his way to meet with his graduate student and former lover. What starts as a simple encounter soon becomes a police matter and then spirals from there. I have mixed feelings about the piece. The idea is interesting, if a little tired, but the supposedly coy reveal is extremely obvious and so the final twist carries no weight. Still, it’s readable and has an ironic feel that is enjoyable.

“Three Gowns for Clara” by Auston Habershaw, is the strongest story in the issue. Told from the point of view of an old seamstress who must make three dresses for the Duke’s daughters prior to Prince Charming’s grand ball, a la Cinderella. It nicely balances the childhood tale with the reality of life in the peasant class. It also nicely mixes the reality of generational differences and the optimism of youth and the experience of age. The conclusion, while broadly telegraphed, neatly ties up the various elements without an easy or trite escape.

“The Nameless” by Melissa Marr is, unfortunately, predictable, trite, and tired. A group of Amazonians live on the mountain and must face repeated attacks by “wolves” (men). Victorie, is the daughter of a woman captured, raped, and impregnated by wolves, but who somehow made it back to the village to give birth. When she goes to the wolves’ village to take the battle to them, the narrator follows. This trip comes at the cost of her friend Mila’s life and the narrator’s freedom until she manages to escape by taking advantage of the headman’s lust, repeating the previous cycle, but with a twist. This type of story is so overused that there is nothing of interest left to be squeezed out of it narratively, and the casual misandry would bring howls of protest were the genders reversed.

“The Leader Principle” by Rahul Kanakia is a thin diatribe against space entrepreneurs like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos. In it, Kevin Slack, a charismatic polyamorous space magnate uses immoral means and targeted marketing to organize a pyramid scheme to keep his business funded. This soon morphs into a semi-organized paramilitary organization held together with promises of sexual conquest and “subjugating women.” It does however get the Mars colony started. It’s hard to know where to start with this story. The fact that the title is a direct translation from the Nazi Führerprinzip, matched with Gobhind’s, the narrator, obvious similarities to Joseph Geobbels, leaves little doubt of how the author wants the story to be interpreted. Yet this element fails to mesh with the critique of crony capitalism or the complaint that the backers of space travel are misogynistic idiots. The conclusion is equally out of place, leaving the reader with nothing to hold on to.

Robert L Turner III is a professor and SF fan. He is currently teaching an honors course on Science Fiction as a mirror of identity.