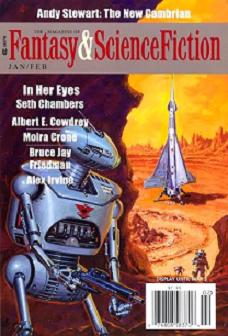

Fantasy & Science Fiction, January/February 2014

Fantasy & Science Fiction, January/February 2014

Reviewed by Chuck Rothman

Fantasy & Science Fiction starts out the new year with some familiar names, plus one who makes a strong return after a few decades.

“The New Cambrian” is a hard SF story set on Europa, where Dr. Schneider, one of the exploration team, had her sub lost while exploring. Ty, her former lover and coworker has to both deal with the loss, and try to figure out what happened. It may have something to do with the life forms discovered there, four-lobed trilobites. There also problems dealing with the relationships involved. Andy Stewart creates a strong mystery with some nicely surprising relationships, but the ending is unsatisfying.

I’ve been a fan of Bruce Jay Friedman since I saw Steambath on public TV in the early 70s. His “The Story-Teller” is on similar ground (and the same ground as an earlier F&SF story, “Yes, We Have No Ritchard”): the afterlife. In this case, Alan Dowling is a retired English teacher who ends up in limbo and given a task: to write a story. The story starts out as an amusing take on what happens to stories when you look at them through academic eyes, and it ends with a wickedly funny punch line that is reminiscent of Roald Dahl at his best. Definitely a delight – especially if you’re a writer yourself.

“The Man Who Hanged Three Times” is Jeremiah Pritchard, who is sentenced to die for the murder of the woman with whom he lived. Of course, he insists he’s innocent, while the judge and, more importantly, the judge’s son Web, insist he be hanged and the matter cleared up. C.C. Finlay takes the situation and uses it to reveal some dark secrets. What is revealed is what all-too-often is an overused pushbutton issue, but in this case it works perfectly and results in an excellent story.

“In Her Eyes” is about Alex, who meets the mysterious woman Song. She is confident and attractive, even though she is not what Alex considers good looking. They date on a platonic basis, and he eventually learns her secret: she is a “polymorph” – a shapeshifting human. The relationship begins to take some surprising turns as Seth Chambers explores the situation in ways that are fresh and new. I especially like the ending, something that comes out of nowhere, but is perfectly sensible once you think about it.

Moira Crone writes about the difficulties of a very difficult relationship in “The Lion Wedding,” where a woman marries a lion. Obviously, this causes problems, and she spends the story coming to grips with what she’s gotten into. The story could be read as a metaphor for any marriage, where the woman and man have to learn to deal with the other’s habits and quirks (just multiplied a bit). Overall, a thoughtful read.

“For All of Us Down Here” is set in a world that is – well not quite post-apocalpse and not quite post-rapture. The world is empty as people opted to be “Singulars,” joining with computers and living in some vague virtual world. Skeet is one of those who stays behind, living with his grandfather after his parents left. He meets up with a Singular, who goes to look for his grandfather. Alex Irvine‘s story portrays a different situation, and leading to another surprising but perfectly logical ending.

Italian author Claudio Chillemi teams up with the always inventive Paul Di Filippo for “The Via Panisperna Boys in ‘Operation Harmony.’” It’s an alternate history where physicist Ettore Majorana is called by his former teacher Enrico Fermi to work on a project to help end the war raging in Europe. But not the World War II of our history. It does something I don’t recall seeing in an alternate history: it alters the time line so, for instance, Einstein lives 20 years earlier and everyone seems to be working in a truly reimagined world. This creates a story that name checks history to good effect, but doesn’t feel bound to it, leading to things that are strange and surprising and allowing the two writers to go wild with imagination.

“We Don’t Mean to Be” by F&SF regular Robert Reed is the story about the capture of a mad galactic dictator and what his enemies try to do with him. I’m not a fan of Reed’s work, and this does little to change my opinion; the artistic conceit of the story structure creates vague characters making them uninteresting. I just couldn’t bring myself to care about the proceedings.

Albert E. Cowdrey is also a regular in the magazine, but his “Out of the Deep” was far better. Pete spent the summer of 1954 in the “Redneck Riviera” on the gulf coast, where he befriends Mac McAllister, the son of a wealthy man, and they become fast friends. As the years go by, Pete is damaged in Vietnam and they lose touch, until Mac asks him to come down to his house, where he is to help act as a bodyguard against the threats of Karl, the local crime leader, who wants Mac’s land. He also meets with the mysterious Yma, Mac’s housekeeper and much more. The story is fast paced with a deeper meaning.

Sometimes a wonderful conceit is more than enough to hold a story together. “The Museum of Error” is one of these: a museum that features various scientific mistakes – the “Rounding Errors Through the Ages” exhibit, robots who insist they’re human, the Never-Right Clock, and Pete the Petrified Cat. Herbert Linden is the Assistant Curator for Military History, and is called to find out what happened to Pete, who may have been stolen by their competitors, the Science Institute. Oliver Buckram’s story is filled with imagination, and is very cleverly constructed, with a mishmash of what seem to be one-liners all come together in the end. Despite the obvious skill, though, the story goes on too long, especially since the mystery and resolution are obvious far too soon.