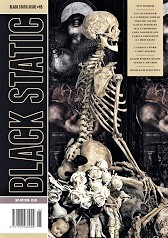

Black Static #65, September/ October 2018

Black Static #65, September/ October 2018

“Imposter/ Imposter” by Ian Muneshwar

Reviewed by Seraph

Seven offerings mark this next to last issue of the year, and true to form, it is a no-rules brawl for which the only casualty might be your sanity. Some stories, like “Imposter/ Imposter” and “In the Gallery of Silent Screams” are well worth the read, fully capable of equal parts psychology and horror. Others, like “Squatter’s Rights,” simply fail to inspire any thought beyond gibbering madness. You will, however, never be bored, and perhaps the world outside will seem just a bit less bright when you are done. That is, after all, how horror should leave you: just a bit darker and stranger inside than it found you.

“Imposter/ Imposter” by Ian Muneshwar

Sometimes the optimal strategy is simply to lead with your best shot, and #65 doesn’t disappoint. One of my biggest complaints about modern horror is that it gives you no reason, in many cases, to care about the characters, their feelings, their fears… or any reason to mourn them. Often the “horror” is often shoved down your throat, almost as if screaming “BE TERRIFIED” out of terror that you won’t be. To me, real horror is delivered with the tendril of a whisper, that takes root in your mind and possesses it, until the fear and the panic rise like an early morning tide. Muneshwar seems to agree, soaring to deliver a character study rife with personal flaws and biting insecurities. The story follows Lyle, a virtuoso sculptor, and his composer husband Édgar across the backdrop of Lyle’s mother Hester staying with them while she works on her memoirs. There isn’t really any time period or location specified, but there are some familiar notes of tension, be it the disapproving and simply unpleasant mother-in-law, or common marital stress. But beneath it all there is a note of discord that exceeds such mundane troubles, and a sense that there is something almost sinister at play. Lyle is more distant than ever, and Hester seems to know something that Édgar doesn’t, beyond her usual nagging and condescension. Édgar is convinced there is someone else in the house, that Lyle is cheating on him, that Hester is hiding something from him. The whisper, when it comes, seems to deliver Édgar’s worst fear all at once, until you realize the whisper was there in his ear all along, leading him to this moment of complete and utter terror. The attention to detail in the story is well-played, and the pace neither overshadows nor underplays the quietly delivered shot of horror in the last few lines. Well worth the read for those who prefer their horror of the psychological kind, rather than the jumpy, bloody pulp horror variety.

“The End of the Tour” by Timothy Moore

I felt like this story had so much potential, but in the end fell flat. The premise is readily horrific, deserving of much more time than it was given. The ending, when it comes, is far too soon for all the possibilities that could have been. This one isn’t about the names, or the places. “I” and “the Cold” are all that matter. “I” is a prodigy rockstar named Sean, quite literally tormented by his inner demons, but like so many other prodigies, driven and elevated to fame by those same demons. And for such, there is always a price. “The Cold” is less clear in nature, although its monstrous inclination is perfectly obvious from the start. Much of what happens is set on a stage in Prague, the rest unspecified, although it’s pretty safe to assume this is a current/modern era, with the repeated mentions of technology and the international media, UN, and EU. It’s a fresh take on a wannabe rockstar selling his soul to the devil for talent and fame, and pleasantly dumps a few worn-out tropes on their heads as it goes. It just rushes to the climax and kind of leaves you there, wondering how you got to this point and why you should care.

“Marrow” by E. Catherine Tobler

I have a love for post-apocalyptic fiction. There is near-infinite potential for explorations of psychology, sociology, morality, and the very nature of what it means to be human. Tobler hits every one of those notes. EATR is a bio-mechanical construct, programmed and set loose, yet more than just lines of code. If the story could be boiled down to one line, it would be “you are what you eat.” EATR is a perfect killing machine, with almost every (un)natural advantage conceivable as a hunter. Life is just one meal to the next, an unending string of kills and consumptions. There is something else lurking within, however, and when EATR meets the not-food (child) Alix, the façade begins to crack. Memories begin to bubble to the surface, emotion, even fear. It’s impossible to discern a timeframe or location in this story, beyond that it is long after something has gone horribly wrong and the drones like EATR were involved. The twist at the end is somewhat predictable, but not so much that I didn’t enjoy it all the same.

“In the Gallery of Silent Screams” by Carole Johnstone and Chris Kelso

What could be a more perfect title? It draws the mind to the tortured, to the grotesque, and delivers precisely that. Johnstone and Kelso truly commit to delving into the mind of madness, and it works. Why should we care about Ong and Ganesan, or their inevitable entwined fate, if the authors do not, or if the characters themselves do not? Quite the opposite, these are characters who are deeply enmeshed in the wheels of fate. Ganesan has been researched and pursued by Ong, who feels drawn to him nearly obsessively by the things they share in common. Their methods, their thoughts, the changes in temperament and in the tempo of their exchanges all speak to characters given life on a page. Set in the White Dice pavilion in Berlin, circa the current era, it is a study in the obscene but is heavily grounded in the reality of life. The “artist” is named Ganesan, and his exhibit is that of one dead foetus after another, all perfectly preserved and grotesque in the moment of stillbirth, guilty only of their mother dying during delivery. Ong is more of an enigma, a stalker of sorts, just come from her own mother’s funeral to spring a trap upon the grandiose and self-absorbed artist. Above each child is the cover of a paperback novel about murderous children, thinly disguised commentary on the displays themselves, and she brings her own novel alongside her thesis. Clearly intelligent, but driven, as if Ganesan is her own personal demon she has come to confront. When it all comes together, when it all ends on the page, it does so in a way that seems inexorable, inescapable, as if it could have ended no other way. It is a critique of the monstrousness hiding inside the human soul, a commentary on the burden of life faced in the presence of the dead, and a damn good read.

“The Pursuer” by Kailee Pederson

This piece was extremely difficult for me to read, but even so I wanted to really dig into it and give it a fair shake. It is almost more a memoir than a fiction, told from the perspective of the daughter of a virtuoso artist, all told from the first-person voice, struggling with his legacy and its impact upon her life and marriage. Central to the recollection is the titular painting, “The Pursuer,” originally called “The Marriage of Myrrha and Cinyras” before her father struck her face from it and murdered the rest of her family, before then taking his own life. A passing familiarity with mythology, judging by the name of the painting, warns of the nature of this father-daughter history, as if such tragedy befalling the rest of her family were to be deemed insufficient. This horror is not of the fictional kind, but of the very real burden inflicted on very real people. This is, to my knowledge, a fully fictional piece. But it could just as easily not be, and that to me has always been the most horrifying reality. The end is a note of resolution, as if she were putting the past behind her, but there is plenty of subtext to suggest there is more going on than that which is on the surface, as well.

“The Gramaphone Man” by Matt Thompson

Some things change a man forever. War is one of them, but sometimes things happen during conflicts that are beyond unforgivable. The line between willing and forced is something that gripped the world in the wake of the Nazi trials after WWII. But less often does someone dig into the mind of those involved in the travesties. This story follows Masayuki, a Japanese soldier during WWII living out the end of his life under the weight of the things he saw and did during the occupation of China. The era is more or less modern, although unspecified, and there is plenty of time dedicated to exploring what is left of his life. There is no question the events of the war haunt him, and have left him empty and hollow inside, although he has suppressed most of them. As a supernatural occurrence afflicts him night after night, the memories begin to flood to the surface, and he comes face to face, quite literally, with the sins of his past. It is heavily implied he is not the only one, and his companions disappear throughout the course of the story, yet the spectre that comes for him is not entirely hostile. There is much on the nature of guilt, on the nature of forgiveness, and on the weight survivors carry, but it is not a story for the faint of heart.

“Squatters’ Rights” by Cody Goodfellow

I believe once in a past review I noted that a certain piece seemed like a drug-addled schizophrenic episode. I owe Cody Goodfellow an apology for underestimating what a drug-addled schizophrenic episode might look like, and my congratulations for definitively depicting one. This, in fact, reads like a drug-addled schizophrenic episode, perhaps laced with some LSD or some really bad shrooms, yet somehow akin to “Solomon Grundy.” I read it over a dozen times, and valiantly tried, but failed to make heads or tails of any of it. There is “we” and “Mother” and some other names strewn about, with no indication of time period, location, or any other point of reference. Years pass in the span of days. Up is down. Rotten is whole and life is decay. It ends with the eerie promise of “we” to return on the midweek breeze, but for the sake of sanity, I pray it does not.