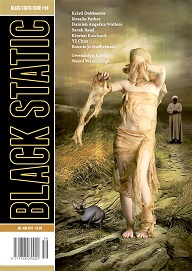

Black Static #59, July/August 2017

Black Static #59, July/August 2017

“When We Are Open Wide” by Kristi DeMeester

Reviewed by Jennifer Burroughs

“When We Are Open Wide” by Kristi DeMeester

Brianne is an only child being raised alone by her mother, a woman haunted by multiple lost pregnancies. The story starts with young Brianne getting her period. Her mother reacts with a mix of tears, pragmatism, and whispering strange things to Brianne in the dark, setting the tone of the world where Brianne grows up, a world where something is terribly wrong.

DeMeester paints a horrifying picture with beautiful prose, the scenes decorated with lines like, “The sound the dark makes when it doesn’t want to betray the thing behind it.”

The normalcy of the modern setting contrasts with the grotesqueness of Brianne’s mother’s reality, and the person Brianne grows to be inside of it. She struggles to feel normal in typical teenage explorations of sexuality, looking for meaning where she has been told it should be. When the supernatural elements finally appear, they are unexpected and shocking in their reveal.

“The Body Is Concentrated Ground” by Kirsten Kaschock

Two spinster sisters have spent most of their lives in self-imposed isolation, never leaving House Creosote, the rambling gothic property that was their inheritance. Felice, with the clear, crisp language of an aristocrat from another time, tells a very matter-of-fact story about their self-imposed isolation, and of Hettie, her sister, who has the strange ability to make herself explode in a mess of gore all over the house, and be reassembled by the following morning.

The story flirts with a dark sort of humor, Felice’s descriptions of her long life with a sister who explodes regularly delivered with a crisp Victorian precision. Felice discusses Hettie’s exploding habit as though it were a drug addiction, even referring to the event as “using.”

The story has a classic gothic setting, with a creaky old house that seems alive and able to do things of its own volition. Kaschock has taken this typical horror setting and tossed something truly weird into it. While not a thrilling or creepy sort of story, “The Body Is Concentrated Ground” is a solid piece of weird fiction.

“The Dreaming” by Rosalie Parker

A modern cautionary fable, “The Dreaming” follows the adventures of Mr. Carmichael in his new career. After taking a class on Shamanism, Mr. Carmichael leaves behind his job as a graphic designer to become a spiritual consultant. He throws a launch party for this new business endeavor, practicing his magic for a group of confused friends while immediately breaking a vow against drinking alcohol.

Mr. Carmichael is clownish in his attempts to “do some good,” dancing in another culture’s costume while tapping a drum in the stuffy living rooms of his clients. The clients range in character and issue, most giving the impression that a therapist or private detective might have been a better investment. Mr. Carmichael seems not to learn much from these experiences, and when he is confronted with a true supernatural problem requiring a Shamanic solution, he is ill-prepared.

An interesting exploration of the meeting place between ambition and hubris, “The Dreaming” has unexpected philosophical depths worth exploring.

“Here, Only Sorrow” by Damien Angelica Walters

A mother mourns the death of one of her five-year-old twin boys. Divorced, with no grandparents nearby, she and her surviving son do their best to grieve. When the boy she still has begins to insist that he is the boy she lost, she lacks the will to help him understand and lets the fantasy continue. As the days go by, mother and son seem to deteriorate each in their own way. Walters pulls the reader down into their sadness, beneath the weight of it, until the reader is suffocating with a mother who sees the things she needs to do but cannot. And yet, cutting through the sorrow that fills this house, is the realization that the situation is not what it seems.

A well-crafted, slow burn of a tale, “Here, Only Sorrow” explores every parent’s greatest nightmare, and then moves beyond it to find a place even more disturbing.

“Ghost Town” by Bonnie Jo Stufflebeam

“Ghost Town” is a story of dark magic and gruesome secrets that explores the difficult question of what the living owe the dead.

A river full of a strange substance flows around a small town haunted by thousands of ghosts, the economy fueled by a black market for human bodies. Three years ago, the body of Rae’s dead wife, Emily, was stolen, which has prevented Emily’s spirit from fully passing on. She haunts Rae every night, having her check on Emily’s elderly mother. Rae longs for change and sets out in search of the person who purchased Emily’s stolen body, hoping to free Emily and perhaps herself.

Stufflebeam has imagined a strange place full of horrors caused both by the power of the river and simple human ingenuity. She raises an interesting question about what people would do in a reality where the dead need a corpse, any corpse, in order to leave the physical world, and there are more ghosts than corpses. This is an eerie tale that leaves the reader with several layers of meaning to contemplate.

“Endoskeletal” by Sara Read

This story takes the classic horror trope of evil being sealed away for thousands of years and creates a well-executed, nightmarish tale of body horror. Ashley, an ambitious archaeologist, ignores rules of policy and respect for a strange discovery found in a Swedish mountain cave, where a strange burial has been hidden away for tens of thousands of years. She finds several jars inexplicably sealed after all this time, and takes one back to the lab, setting off a horrifying chain of events.

The story happens in three locations; the cave, the side of the mountain, and the archaeological lab. Told from Ashley’s first-person perspective, from the beginning we share her physical experience of each location, the dampness of the cave, the sharp rocks of the mountain path, the comforting white light of the lab. The reader is feeling what Ashley feels by the time terrible things start to happen, and the controlled environment of the lab is traded for chaos and darkness.

Not a story for the squeamish, “Endoskeletal” reads like a fevered nightmare full of warnings about foolish mistakes.

“To Dance is Feline” by Yz Chin

Set in ancient times and told through a black cat’s eyes, “To Dance is Feline” explores the power of superstition and monsters it invokes. The young cat who tells this story is raised by her mother in a human household, after a long search for a safe place to have a litter. Both she and her mother are black cats, and when none of the humans will accept blame for an unfortunate accident, the devil is invoked and the humans turn fearful of the cats.

The young cat is taught many things by her mother, including her mother’s disdain for the greatest difference between cat and human; an inability of humans to claim their mistakes. As the humans become increasingly fearful of the cats, they become the monsters of the story, while pointing shaking fingers and screaming about the devil.

Often fiction written from an animal’s point of view emphasize the strangeness of such a perspective, using techniques like childlike interpretations of technology, very literal names for things, or other displays of innocence. There is none of that here to distract from the darkness of the story. The young cat’s innocence is only inexperience, which her mother counteracts with a variety of lessons about the harshness of the world. Chin has crafted a “cat point of view” story that feels fresh, using this style to show the reader some difficult truths about human beings.