Reviewed by Stevie McMichael and Chuck Rothman

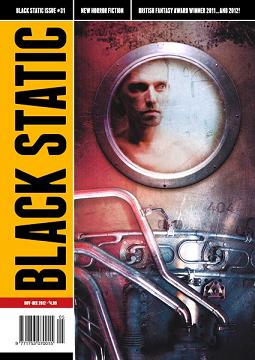

Black Static #31, November-December 2012

Reviewed by Stevie McMichael

This issue contains a collection of wonderfully unique ghost stories. Some of the specters are real, while others only haunt the minds of the characters. Many feature figurines and mannequins, some obviously sentient, and others whose consciousness is only hinted at. Sometimes, the things that are the scariest are the ones we readers don’t see.

In “Barbary,” by Jackson Kuhl, a nineteenth-century sailor suffers from ocular hypertension, a painful condition that leads him to try hundreds of quack remedies. Distrusting doctors, he finds a pharmacist in Barbary, who prescribes him an unusual medication: mummy fragments. The remedy works, but the apothecary only carries a finite amount, so the narrator is forced to seek a similar treatment elsewhere. He discovers a back-street vendor of mummy parts and powders, and finds himself admitted to a small community of fellow mummy-users.

It’s not until he goes back to sea that he realizes there’s been something off about his ‘club’ the entire time: there were always more people around him after he’d smoked than there were when he’d arrived. He discovers, through his stops to ports all over the world, that it’s the dead he sees, visible only to mummy users. Some of them even assist him, and he adjusts to their presence while remaining blind to his habit’s effects on himself. A fellow sailor says he’s looking ill, jaundiced, and points out that he’s always thirsty. His medicine is doing more than ease the pain in his eyes.

I thought this story was very well-done, spooky and disturbing, and the ending made me a little ill, in the best possible way. The prose is realistically archaic without being awkward or stiff, and the narrator’s condition was described so clearly that I couldn’t blame him for his desperation to find relief.

In Seán Padraic Birnie‘s “Sister,” a boy mourns his dead sister, who had obviously been their parents’ favorite. His sister had been beautiful and talented, while he, in his own words, shows no aptitude for any of her work.

In his grief he builds a model of her, using the materials she once used in her artwork, and brings it to life like a kind of golem. What he achieves is an imperfect copy of the person she had been in life, but his parents buy into the charade, forcibly forgetting that she had ever died. Only Daniel remembers. He says that he never expected his attempt to work, and it sounds like he wishes a little that it hadn’t.

This story left me unsettled, in a good way. The atmosphere is dark and claustrophobic, the narrator Daniel a boy lost in a despair his parents don’t care enough to be aware of. The sister he creates isn’t much like the one who died, seeming mentally incapacitated, but she’s still their parents’ favorite. It made me wish somebody would just give the poor boy a hug.

“The Perils of War According to the Common People of Hansom Street,” by Steven Pirie, is exactly what the title says: a story about a neighborhood community living through World War II. It follows Mrs. Elms, an elderly woman who refuses to admit her husband committed suicide; Dobson, a boy manning the gunnery crew that defends the street; Mary, a code-breaker; Charlie Higgins, a pilot, and Anderson, a man who is not what he seems.

One by one the characters perish in an air-raid. Only Mary escapes, waved away by Anderson, and only Mary realizes what he is – Death incarnate. She doesn’t know why he lets her escape, and she doesn’t stick around to find out. This is not a compassionate Death; she sees how much delight he takes in his work, that he exudes cold and hopelessness.

This story has a streak of morbid humor that I really enjoyed. Some of the characters have a kind of “keep calm and carry on” mentality, even while they’re dying. Short though the story is, they all had time to develop as distinct individuals, which made their deaths quite tragic. Even Anderson, the reaper who enjoys his work, has a dark amusement about him that gave me a good sense of who he is.

In “The Things That Get You Through,” by Steven J. Dines, a husband, James Graves, loses his wife in a traffic accident.

The story follows the five stages of his grief, each of which sees his sanity slip a little more. His wife had told him she was leaving him just before she died, and we discover a little later that he too had cheated, online rather than in person. He holds arguments with her, and he’s uncertain whether or not they’re hallucinations, and turns an old mannequin into an effigy of her. He’s also stalked by three teenage girls whom he calls the Three Little Witches, who also might or might not be real.

Eventually he meets a woman named Maureen, with whom he begins a relationship that looks stable from the outside. James continues to be haunted by his wife’s memory, however, to the point where he suffers terrible insomnia. He believes he must get rid of the mannequin to move forward.

This tale was eerie, and it delved into the character’s madness quite well – occasionally to the story’s detriment. Sometimes the prose was as convoluted as the narrator’s mind, and I found I had to read several passages more than once to make sense of them.

“Skein and Bone,” by D.H. Leslie, tells of two sisters vacationing in France. They pause their journey to visit a chateau, which is listed as a spot of historical interest in their guidebook.

What they find is an abandoned building filled with mannequins, all dressed in historical costumes. Libby, the elder, thinks it’s fascinating and beautiful, but her younger sister Laura thinks there’s something very wrong with it. They’re caught by a woman who insists they stay the night, which delights Libby but troubles Laura. Laura warns her sister not to go back to the room with the dresses, still uneasy, but Libby ignores the warning and sneaks out in the middle of the night. Laura is likewise tempted out of their bedroom, and the pair realize they’ve become prey for their quiet hostess in black.

This story was short, entertaining, and pleasantly disgusting in places. The plot was a bit predictable, but the characters were unique enough to carry it for me.

In “Two Houses Away” by James Cooper the narrator watches his elderly neighbor Albie reunite with his dead wife. Understandably, he wants to know what’s really going on, so he goes to check on Albie. What he finds is not the deceased Martha, but a mock-up of her, so crudely done he at first doesn’t understand how he could have mistaken it for the real thing at all. He realizes, too late, that the creation is not what it seems.

This story is very short, and I wish it had been longer. The premise and characters intrigued me, and I would have liked to know more about how Albie’s creation became what it is.

On the whole, I really enjoyed this issue. Some of the stories worked better for me than others, but they were all engaging, and some were incredibly creepy. A nice mix of the gruesome, the unsettling, and the occasional hint of very dark humor.

Black Static #31, November-December 2012

Black Static #31, November-December 2012

In “Sister,” the protagonist morns his sister’s death by making a mannequin of her (mannequins have a prominent place in this issue) with unexpected results. Seán Padraic Birnie‘s story is very slight and not particularly horrific.

“The Perils of War According to the Common People of Hanson Street” is primarily a description of the inhabitants of a particular London street during the Blitz, as they deal with the war and with death around them. It’s a series of vignettes, with some slight connection between them as their stories play out. Steven Pirie does a good job of documenting the characters of the street and bringing them to life (and death).

Steve J. Dines contributes “The Things that Get You Through,” about James Graves, whose wife dies in a crash immediately after telling him she’s leaving him for another man. Emotionally distraught, he starts doing various tasks to deal with his grief, finding a mannequin in the basement that becomes central to his moving on. While well-written, the story goes on far too long documenting the little things James does to go through the process of grief, with a payoff that didn’t make the wait worth it.

“Skein and Bone” is the story of two sisters, Laura, who is the sensible one, and Libby, who’s out to have a good time. They’re on a trip to France and, on the way out of Paris, Laura decides to be more spontaneous and visit a castle in a small town on the way. But the castle is derelict and the town is deserted. Not knowing they are in a horror story, they decide to break into the castle and discover a strange welcome, including a room filled with mannequins showing elaborate dresses that Libby is envious of. V. H. Leslie writes well, and the two sisters are interesting characters, but the story treads a path so well-worn that it ultimately becomes an inadvertent parody of a horror story.

Finally, James Cooper provides “Two Houses Away,” where Tom notices his neighbor Albie walking with his wife, who died a few weeks earlier (another theme of this issue is dealing with grief). He goes to investigate and finds something (a type of mannequin is involved). I’m not sure what. The story tries to create a mood rather than a plot and I didn’t care for it.

The six stories in issue #31 all show great skill in the ability to paint characters and settings, but other than “Barbary,” there isn’t much to them other than a mild frisson. There is also a certain sameness in execution, with dead relatives and mannequins an important element far too often. More variety would have helped.

Chuck Rothman’s short story, “The Last Dragon Slayer” will be appearing any minute now in Unidentified Funny Objects.