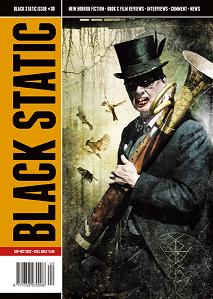

Black Static #30, October 2012

Black Static #30, October 2012

Reviewed by Colleen Chen

This issue of Black Static has a nice range of tales for the intelligent horror reader. There’s not much gore to be found here and plenty of psychological horror, creepy supernatural elements, and some ghosts.

“The Pig Farm” by James Cooper is the first story, and I found it the scariest. Nothing supernatural ever appears in the story, but it’s told from the point of view of Emma, a young girl whose terror is real and quite visceral. It begins with Emma spending the night tethered to a wooden scarecrow—a punishment meted out by her father for some transgression or defiance she doesn’t even remember, and probably did not commit. The worst part of the punishment isn’t physical, but psychological—her father has told her stories of an undead Weeping Farmer, crying tears of blood as he seeks his lost daughter and listens for any sound of distress as he swings his long-handled axe.

The tone for the story is set in that first scene. With a sense of impending doom hanging over us, we meet Emma’s father, whose mourning for his wife tips him ever deeper into spells of cruelty, and Emma’s two psychotic brothers. Emma finds her only comfort in the companionship of Nathan, a dreamy, moon-faced hired hand who takes care of the pig. But a train of tragic events beginning with the sickening of the pig brings us full circle back to the field and the Weeping Farmer.

The heroine is terribly likable for her sweetness and innocence, but she is the ultimate victim—helpless and despairing, accepting of her doom. It’s an effective recipe for an agonizing and haunting read that is beautifully written.

“All Change,” by Ray Cluley, is an odd, clever story that the author dedicates to Ray Bradbury. Robert is a 76-year-old man running to get on a train…and then we learn that he’s spent decades as a sort of vigilante killer of monsters in human form, following an inner sense that identifies them at the train station. We aren’t sure he’s not crazy, but we know that he sees the monsters—often filled with gelatinous ooze or bearing other traits of monsters through the literary ages. This story deals with Robert’s final journey on a train, searching for his next victim; he can’t tell who the monster is, and by the end we can’t tell either, and it probably isn’t who we thought it was.I understood and appreciated this piece a little better after reading a summary of the story Robert skims on his train journey—Ray Bradbury’s “The Jar,” with its themes on the nature of evil. References to that and other elements of the history of the horror genre are woven throughout the piece. Readers looking for pure thrills or straight horror won’t find it here, but there are plenty of other things to enjoy about this story, among them some very effective and creepy visuals, and passages such as this one that I loved:

Fiction is where we find our fiends, that’s what Robert knew. And none of that unconscious or subconscious rubbish; we knew what we were doing when we created such things. We put them in stories to be told around campfires, and later we put them in books, lots of them in lots of books, and that way people would know. Robert’s greatest weapon was his library card. At least, it used to be. Recently he wasn’t so sure. Monsters wore hockey masks, gloves with blades, something white-faced with a stretched open-jaw. Now, at his age, he was thankful that they sparkled, was glad to fight noseless foes with a curious grasp of Latin and a name that shouldn’t be spoken. Diluted devils. Paper scarecrows. Easy.

“The Wayside Voices,” by Daniel Mills, offers a unique take on the archetype of serial murder at an anonymous place of lodging, integrating terror and mercy into a dark tale of the inexorable power of the Wayside Inn. It begins, I believe, in Civil War times; the Inn is a coincidental destination for lonely and despairing travelers.

The narrative shows deepening angles of the story by layering first-person points of view. It begins with a traveler stricken with grief over his dead son. Despite efforts by the innkeeper’s daughter to save him, and his avoiding the poison offered by the innkeeper, his own sadness seals his doom.

We next learn of the innkeeper’s motivation for his murders, and of how his daughter came into his life. Before we reach her point of view we already see her desperation from several angles; through her eyes the story reaches an emotionally painful climax as she tries again and again to escape her father and the Wayside.

The story is effective. It evokes the same sorrow and despair as its characters feel, yet prevents readers from truly caring about anyone in it. No one is evil here, but they are all flawed beyond redemption. Still, the ending has a note of bitter triumph that I found satisfying, and the atmosphere and layered narrative are exceptionally well done.

“Recurrence” by Susan Kim will doubtless remind some readers of movies like The Others or The Sixth Sense when they realize, early on, that it’s told from the point of view of a young female ghost who doesn’t quite realize that she’s dead. It’s an especially poignant point of view, and very well executed—Emily wakes from a nightmare of a car accident, and she repeats the same pieces of her day every day, everything exactly the same except for noises in the house. She is with her brother and her cousin Chloe, who was supposed to stay only a few days but remains indefinitely, and her mother, who sleeps and drinks all the time. They never leave the house.

What this story offers that is unique among stories from the point of view of ghosts is it feels very real to me, the scattered consciousness, the skipping around and repeating of scenes, the utter lack of linear time and space. It’s expertly crafted, a tight piece that shows the agony of being trapped in ghosthood.

Carole Johnstone’s “Sometimes I Get a Good Feeling” offers a welcome reprieve from the hopeless despair of the prior pieces—this darkly humorous piece about the discovery of a pest under the narrator’s house had me snickering throughout. The pest is called by the innocuous name of “critter,” and its tiny droppings that first alert the narrator to its presence deceive us into thinking it’s something small, maybe raccoon-sized. Then we gradually get clues that indicate it’s bigger than we think…then bigger than that…and even bigger.

The main character is a man meticulous in appearance and behavior, acutely conscious of how he’s seen by his neighbors. He’s bought all the government-recommended deterrents to Critters and has his place examined far and above the demands of prudence. Thus, he tries to hide signs of the pest as, armed with Drano and bleach, he leads a vengeful one-man crusade against it.

Most of the action takes place in the crawl space under the house, and Johnstone does an excellent job of evoking that creepy-crawly feeling that something might happen when you’re in a tiny, dark enclosed space trying to kill something that you can’t see. I love the main character, particularly his hilarious inner dialogue! This is my favorite story of the issue.

“The Orphan and the Bad, Bad Monkey,” by David Kotok is narrated by an orphan boy turned street performer, dancing with a monkey to the tune of a music box under the watchful eye of his caretaker, Mr. Yang. Mr. Yang has brought up the boy with tales of mines deep underground where orphans and unwanted children spend their lives digging in endless dark, eating mushrooms fertilized with their own feces. Other elements of Mr. Yang’s tales of terror include a greedy, sharp-toothed Taxman who takes children from poor families, and the Leaders, godlike men who make the laws. The boy believes that he’s lucky to have the life he does, because he’s told he’s stupid and thus would certainly have been for the mines. So he performs with a monkey he doesn’t like, his sole purpose to make the audience “happy” so that it will give them money.

The voice in this story is impeccable, that of a small boy in an Asian land full of color and spice and exotic foods. We get a sense of the emptiness the boy feels as he imagines parents who love and seek him; he gets neither kindness nor the feeling of being wanted from Mr. Yang, and ends up talking to the monkey as Mr. Yang talks to him—telling him he’s stupid, and lucky not to be in a mine. As the boy and the monkey sit in a dark room filled with dead animals, waiting for a drunk Mr. Yang to wake up, the emptiness transmutes into a surreal climax.

This story feels sad rather than dark to me. It’s heavy with metaphor, so not completely straightforward; I got confused on my first read, and not quite sure the somewhat morbid conclusion felt appropriate. This is one that I would probably like a lot more if I could get the author to explain it to me. Like “All Change,” I think it’ll appeal to those who “get it” but not to others.