“The Overseer” by Tim Casson

“The Overseer” by Tim Casson

“Extreme Latitude” by M. G. Preston

“One Last Wild Waltz” by Mike O’Driscoll

“The Empty Spaces” by Alison J. Littlewood

“The Moon Will Look Strange” by Lynda E. Rucker

Reviewed by Dave Truesdale

Tim Casson‘s “The Overseer” takes place in a dark, gloomy, worldwide post-economic Crash London sometime around either WWI or WWII (most likely WWII, but it’s hard to tell from the bits of background description offered–some references seem to conflict, time-wise for me–and makes little difference to the point of the story).

Darius has been placed as overseer/manager of his ailing father’s vast fortune. He fails to take his father’s advice, mismanages the empire and loses it all. Following his botched attempt at suicide that leaves him unconscious, he then finds himself in a strange town totally destitute and grubbing for work. He eventually finds work in a dirty, unsafe mill, with cruel hours and an even crueler overseer, working for a pittance (think Dickens). Amidst this hopeless, desolate existence of pain and misery, and through story circumstances involving murder, he comes to possess the mask of the previous overseer—the mask only the overseer wears in the mill, for it is a gas mask that filters the dusty air of the mill, a privilege only the overseer is granted. He soon learns the mask does more than filter the air, and has certain properties that resonate with an ancient artifact he had once seen in his father’s mansion before his downfall.

Along with a love interest that figures in his planned escape from the mill, the two friends he has acquired while at the mill, and the secret of the mask, we see a morality tale unfolding where scales are balanced as they inevitably must be, and how Darius’ life is forever changed by his inseparable relationship with the grotesque mask, as he becomes, once again but in a quite different fashion, “The Overseer.” Well written and enjoyable, notwithstanding the overriding grimness of the tale.

M. G. Preston‘s “Extreme Latitude” is related as diary entries from a research scientist cloistered during the Arctic winter. It’s the usual formula of how the isolation and months of darkness can drive one mad. In this case, the scientist’s self-delusions bring about murder and suicide, replete with voices in his head and biblical references. Professionally written, it brings little new to this tired scenario, and is thankfully only a little more than two pages in length.

Mike O’Driscoll has penned an elegantly understated horror story with “One Last Wild Waltz.” A young man in his prime flies from his new home in Australia to his brother’s funeral in England. The older brother’s home has burned, leading to his gruesome death. The younger brother (with a new love at home in Australia) was once involved with his brother’s wife, whom his brother stole from him, mostly because he could. She regrets her marriage to the (now revealed) abusive older brother and seeks comfort in her former lover’s arms. He is torn between his new love and his old flame. Against this backdrop, that of the funeral, the partially intact burned house, the widow’s entreaties, and other village and familial reminiscences and history, and set in the dead of winter, O’Driscoll calmly leads the reader through this bleak landscape of regret, and a deceased brother yet bent on tormenting his wife and brother—from the grave. How this torment manifests itself is well-handled and, again, understated, which in this case only adds to the chilling resolution. A truly professional performance, with just the right amount of precise and well-chosen detail to make the story come alive in the mind of the reader; we feel we know this place, this person, this general situation in which he finds himself thrust, and can easily empathize with the doubts, fears, and anger he lives with, and how he attempts to reconcile them. But can his own internal struggles, and the choice he makes regarding his brother’s widow, overcome the meanness and hatred of his deceased brother? Only by reading “One Last Wild Waltz” will you get the answer.

At a scarce two pages Alison J. Littlewood has turned in another quiet gem. “The Empty Spaces” employs the metaphor whereby some ocular conditions, or diseases, lead one to fill in the empty visual spaces with things (people, objects) the eye can no long see, and extends this phenomenon to the mind filling in thoughts where once there was an empty space. It’s a clever conceit, and the author works it carefully, delicately, to tell the story of two old friends who married sisters. Through no real fault of their own both sisters were murdered, and we now find the old gentlemen inhabiting one large house in their waning years, taking care of each other. One begins to see images of Marilyn Monroe, then his dead wife, then non-existent funeral processions outside his window. The other discounts these visions as evidence of the doctor’s diagnosis of the eye filling in the empty spaces with unusual objects.

One quiet day the skeptic hears doleful music played from his friend’s phonograph upstairs. While on his way up the stairs the music stops. What he discovers in his old friend’s room, including the music on the phonograph, changes his few remaining years forever. A most endearing little tale indeed.

Like the previous pair of stories, Lynda E. Rucker‘s “The Moon Will Look Strange” involves the death of a family member. O’Driscoll’s “One Last Wild Waltz” featured the death of a brother; Littlewood’s “The Empty Spaces” revolved around the death of wives, and now the triptych is complete with “The Moon Will Look Strange,” which uses as its springboard the death of a couple’s young daughter.

A young man and wife are unable to weather the tragic death by auto accident of their beloved daughter. As their marriage crumbles the man takes the advice of a long-time hippie-type friend who dabbles in New Age mysticism and magic, but whom his wife has warned him against since they first met many years ago. Desolate, the bereaved father departs Oregon for Europe, finds himself penniless and destitute in Spain, and a broken man—both physically and psychologically. Still following his friend’s magically-inspired mumbo-jumbo (and through story detail omitted here) his daughter appears to him in his lonely room, then becomes more solid and real, until… Well, just know that the devil takes many forms and is aptly known as the Great Deceiver, and one of his many deceptions takes form when “The Moon Will Look Strange.” A satisfying tale of guilt and grief, and how the Devil takes advantage of us best when we are at our weakest.

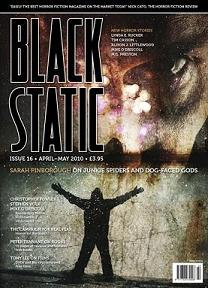

Overall a fine issue, with (as is always the case with Black Static) every story wrought in professionally-crafted line-by-line prose, not to mention in this particular group the proper marriage of atmosphere, tone, and mood as required by each story. There are no extreme horrific fireworks here, little blood or gore save for one story, but rather an assemblage of (for the most part) somber, grey, emotionally-driven supernatural stories (albeit one quite wistful and touching) that I found most satisfying.

Black Static‘s website can be found here.