For this issue of Black Static we present a pair of reviews, the first by Carla Billinghurst, the second by Carole Ann Moleti.

For this issue of Black Static we present a pair of reviews, the first by Carla Billinghurst, the second by Carole Ann Moleti.

“Eight Small Men” by James Cooper

“The Knitted Child” by Simon Kurt Unsworth

“Maximum Darkness” by Alan Scott Laney

“Babylon’s Burning” by Daniel Kaysen

“Death by Water” by Sarah Singleton

Reviewed by Carla Billinghurst

Plot

Characters

Satisfying ending

Horror! That wonderful mix of bogeymen, taboos and laughter. It should lift the hairs at the back of your neck to begin with, slowly freeze your spine as the story unfolds and leave you with your stomach muscles clenched just a little too hard for comfort. And maybe a bit of an appalled chuckle! It is about holding up an act of evil against our sense of humanity, that delicately constructed citadel of morals, rules and sympathies which we build to ensure we don’t suddenly wake up and realise we’ve eaten granny. Oops.

“Is this wrong?” should be a question we can all answer by now, but the challenge is always the shifting ground of “wrong”. We love to play with moral conundra. In March 2001 in Germany, Armin Meiwes posted an Internet ad asking for “a well built 18 to 30 year old to be slaughtered and consumed.” The ad was answered by Bernd Jürgen Brandes. After killing Brandes and eating parts of his body, Meiwes was convicted of manslaughter and later, murder. But is murder between consenting adults wrong? Of course it is, but what if Meiwes had just eaten a part, say, a leg? We worry away at these questions like a dog with a bone. Hmm, wonder whose bone that is? So, the fun of horror stories is that we can pose questions and ask “How wrong is this?”

Which is exactly what the stories in this issue of Black Static achieve. I enjoyed all of them – highly recommended.

There are no monsters and nothing supernatural in James Cooper‘s “Eight Small Men.” It is a story about survival: how two orphans survive their foster-mother but grow up still fearing the arbitrary punishments she handed out. The story flows like the polluted creek the children play in, carrying along its cast of damaged characters. This is a world of children; even the adults in control are children. The one glimpse the narrator has of how the adult world might be a place of compassion and tenderness is eclipsed by terror and we come to understand that it never returns.

My favourite in this issue is “The Knitted Child” by Simon Kurt Unsworth. It is a poem of a tale about the pain of miscarriage and how magic can only ever be a temporary solution; we have to find our own strength and cannot borrow it for long. I’m glad to see Unsworth has a story collection being published later this year; I’d definitely read more from him.

In “Maximum Darkness” Alan Scott Laney works too hard, for my taste, at trying to build up anticipation. The tone of the story is ominous without any of the subtlety that really puts ice down your spine. The descriptions of the daily trivia that annoy the main character, Robin, are highly entertaining and he is a fascinating character but in the end there isn’t enough cause and effect to drive the plot. I was left wondering how some of the ideas were supposed to fit in.

“Babylon’s Burning” by Daniel Kaysen visits that well-known realm of demonic activity, the boardroom. Ah, corporate evil thy name is legion! This story has everything: sex, blood, and evil people in suits! That being said it is well written with solid characters and a satisfying ending.

Sarah Singleton offers “Death By Water,” a lovely re-telling of an old myth – I’m not telling you which one because that would spoil it. Singleton calmly lays out the steps of the story, slowly revealing the crime. There is some rich characterisation in here especially with the main character, who is initially portrayed as an uncomprehending innocent, someone looking for love who encounters magic and cannot resist; but ultimately revealed as so greedy for love he will risk everything, even what is not his to risk.

“Eight Small Men” by James Cooper

“Eight Small Men” by James Cooper

“The Knitted Child” by Simon Kurt Unsworth

“Maximum Darkness” by Alan Scott Laney

“Babylon’s Burning” by Daniel Kaysen

“Death by Water” by Sarah Singleton

Reviewed by Carole Ann Moleti

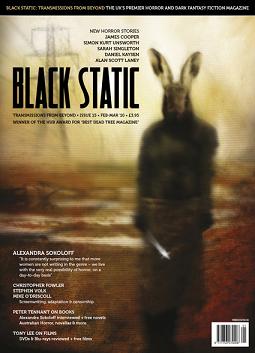

Black Static #15 contains five stories: two have siblings struggling with mental illness, and only a rat’s tail and comic book’s worth of speculative content, two centered on a woman’s despair as seen through the eyes of another, and one gruesome portrayal of perfectly sane insanity.

In “Eight Small Men” by James Cooper, Vic is escorted into a sickroom by a woman reminiscent of Nurse Ratched in Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Denise bears an uncanny resemblance to The Matron who once tortured Vic and his brother Franklyn while they lived with her and her husband, Aubrey. She is dead, Aubrey is dying, both of cancer. Vic and his brother Franklyn have returned for closure, not to pay their respects.

Like the horror of mundane existence among the mentally ill that Kesey chronicles, Mr. Cooper uses Vic’s flashbacks to bring us to the present and ends the story with the significance of darkness, and of the eight small men hidden within it.

I perceived brief flickers of speculative content: that Nurse Denise was really the Matron reincarnate, and that the red-eyed creature that awaited Vic and Franklyn amongst the trash in the drainage tunnel was more than a rat. But no matter because the suspense kept me turning the pages, and there is plenty of horror in realistic fiction.

“From the first stitch, tying thread to thread, the old woman had let her needles caper and weave, ignoring the pain that scoured her knuckles and that burned like white fire in the wasting flesh of her wrist because this is creation, she was knitting against loss, was knitting hope.”

A storyteller speaks for the mute doll in “The Knitted Child” by Simon Kurt Unsworth. The gift of a loving grandmother to soothe her granddaughter, bereft over a miscarriage, is crude, unfinished, a product of “weary, brittle magic.”

“It came into existence with the knowledge that it could not grow, had no hands to hold out nor voice to speak its feelings, but it had love to give and solace and tenderness, and it wanted to belong. This is what it knew.”

As the doll silently observes the anguish of a young woman, and the touching, helpless floundering of her husband as he tries to help, the emotions blaze out of this evocative story, which is more bittersweet than creepy.

In “Maximum Darkness” by Alan Scott Laney, Robin Parker can’t bring himself to tell his mother what he’s looking for, or to call his sister and ask if she just so happened to take the comic book he desperately needs. The one responsible for the nightmares. The “classic piece of pulp imagery, with a howling beast bearing down on a group of strangely submerged humans that screamed in horror as they sank into each other.”

Questions unasked can not be answered, and pleas for help unheard can not be heeded. What Robin instead finds left behind in the attic provides his answer, and his mother and twin sister are left wondering why.

“Babylon’s Burning” by Daniel Kaysen is a chilling combination of the movie The 40-Year- Old Virgin and something far more sinister: human greed personified by the workers at Bell, Chase, and Herr who “worship the gods of gold and silver, bronze and iron, stone and wood.”

A severed hand writes in blood on the wall, and Daniel is convinced it’s a magic trick. The CEO likes his interpretation of a Babylonian prophecy so much, he makes Daniel an offer he can’t refuse, even though Daniel knows “a mind can only see so much before it catches fire.”

Beware of a literal interpretation of this story. Loaded with symbolism and nuance, it isn’t as preposterous as it seems.

“Death by Water” by Sarah Singleton is the third in this issue which hints at how deep the chasm of depression can be, and how some can not be pulled out no matter how hard their loved ones try. Three skilled seers can’t reach Jeanette. Her husband Ian, desperate for answers, can’t either. And that seems to be the way she wanted it, as did Robin Parker in “Maximum Darkness”

Though the themes are similar, I couldn’t help but think that the different outcome in “The Knitted Child” is because of one thing: hope–a crude, ephemeral notion that struggles to make itself heard.

Ms. Singleton’s use of flashback gives this story a more ethereal feel than Mr. Kaysen’s straightforward, shocking narrative in “Babylon’s Burning.” It cushions the horror but not its deep sense of despair.

The glimmer of hope inside Vic might be what draws him back to face the “Eight Small Men,” as the lack of same pushes Robin into “Maximal Darkness.” If I am correct, that’s an example of a superb editing.

I also enjoyed the interviews, reviews and commentaries by Christopher Fowler, Stephen Volk, Mike O’Driscoll (screenwriting, adaptation, and censorship), Peter Tennant (books and an interview with Alexandra Sokoloff), and Tony Lee (films).

Issue 15 of Black Static caused me a couple of restless nights and inspired lots of thought–just what a magazine that publishes dark fantasy and horror should do.

Black Static‘s website can be found here.