“We, Who Live in the Wood” by Paul Finch

“We, Who Live in the Wood” by Paul Finch

“The Eleventh Day” by Christopher Fowler

“Hootchie Cootchie Man” by Maurice Broaddus

“Survivor’s Guilt” by Rosanne Rabinowitz

“Teen Spirit” by Gary McMahon

Reviewed by Steve Fahnestalk

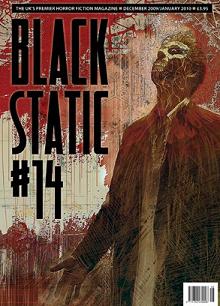

Black Static, companion magazine to Interzone, bills itself as the UK’s “Premier Horror Fiction Magazine”—but that description is inaccurate. I think they should change that to “Premier Dark Fantasy Magazine,” as that more accurately describes the contents of this issue, which is probably typical for the magazine. It’s glossy b/w, with a color cover, handsomely illustrated — but not all the stories are, in my opinion, categorizable as horror.

There are also news, commentaries, book reviews, movie/DVD/Blu-Ray reviews and so on; humorously enough, the “contents” page is the “innards” page. (As you can probably guess, this is my first look at this magazine.) But let’s look at the stories.

“We, Who Live in the Wood” by Paul Finch is a fooler. I got through the first couple of pages, thinking, “Oh, God—another standard, formulaic English horror story. If I want to read that, I’ll revisit M.R. James,” who at least originated much of the twentieth-century genre. But I was wrong, and the story changed in mid-stream to become something surprising and dark, like a chocolate with a straight pin in the middle.

David and Sonja are on their way to a “holiday” in or near Dartmoor; rather than a pleasant getaway, it’s supposed to be a rest for Sonja, who has just had her third miscarriage. Unfortunately for David, who rented the cottage by phone, it’s on the edge of the moor and, rather than being a bright holiday let, is a brooding heap of ancient stone on the outskirts of which is Wistman’s Wood, supposedly haunted. There’s no satellite, and the brooding grey skies of the West Country are not exactly conducive to a pleasant getaway that will take Sonja’s mind off her problems.

Well, we’ve seen this scenario (or similar ones) many dozens of times. Yes, Sonja, who’s supposed to be asleep, makes her way into the woods on a dark’n’stormy night in her nightgown and bare feet because “she heard children crying”… and yes, there are legends about lost children in Wistman’s Wood, but the story makes a strange turn just when you think you have it figured out and becomes a really good horror tale that owes little to convention.

“The Eleventh Day” by Christopher Fowler is one of those stories you’re going to remember for a long time. If I were an awards nominator, this little chiller would definitely get a nod from me. It’s the story of Mia Terebenin, who’s a secretary in St. Petersburg, Russia, and who works in an old building that is going to be superseded by a much newer data facility outside the city. Mia is cataloguing some old documents pertaining to postwar Russian-American oil initiatives. Her colleagues on her floor have already moved to the new building, and Mia is closing out some stuff in preparation for her own move. On Friday afternoon, nearly alone in the building, she takes the elevator down rather than descending a steep, dark staircase in high heels.

In the elevator, she meets a stranger, who becomes trapped with her when the elevator suddenly stops between the fourth and fifth floors. She learns his name is Galia, an electrician—but his knowledge of electrics proves insufficient to get the elevator moving again. They are unable to pry the doors open, and resign themselves to spending the night in that box, until someone comes in on Saturday, where they might attract some attention (due to various factors, Mia’s cellphone is unusable; Galia has left his on his desk, as he was “only going down for a smoke.”).

I kept asking myself, where is Fowler going with this? What horrors is he going to visit on us, the readers—will it be gore galore? Slasher heaven? Cannibalism? Something darker? I can’t tell you, but all I will say is that I didn’t see it coming. And I’ll bet you don’t either. A real chiller, this.

“Hootchie Cootchie Man” by Maurice Broaddus doesn’t tread any familiar horror ground either; I hesitate to even put this in the “horror” category. I’d call it “dark fantasy” and let it go at that. For those who are looking for gore, be advised that this isn’t a slasher any more than the Fowler story was. On one level, it’s a story of synchronicity and perhaps some kind of religious feeling; on another level it’s a story of human relationships; on a third level it’s kind of a jazz riff, and I can’t explain that last comment. Broaddus is familiar with a lot of old blues classics, and uses them to great effect (most notably Willie Dixon’s “Hootchie-Cootchie Man”).

It’s the story of Nathaniel Johnson, who boosts cars for a living, and is not so much a victim of, rather than a user of, synchronicity—from little things, like always pulling the right change out of his pocket, to bigger things, like getting the exact amount for a car that he needed to catch up on his rent and pay next month’s… and maybe bigger things than that. When Nathaniel meets a teenaged cokehead several times in the span of only a day or two, she begins to have a profound effect on his life despite her not even recognizing him when they meet again.

I’m not sure about the ending. I liked the story, the setup and the description of not only the characters, but Nathaniel’s life—but the ending didn’t really tell me anything. It’s the reason I don’t think this is horror; but your mileage may vary. I found it sad, in that Nathaniel was unable to change his life, but not horror per se.

“Survivor’s Guilt” by Rosanne Rabinowitz again doesn’t fit the “horror” category, even though the main character is a vampire. It takes place in London, although the time is extremely vague; if one character hadn’t been described as being killed in a concentration camp in Germany some years before, I would have thought it was pre-WWII; certainly the feeling here is revolution and unrest. Our unnamed protagonist is over 200 years old and a survivor of many revolutions in many countries.

She has come to a meeting organized by the Left; to hear a well-known poet read, some light entertainment, and some speeches. She has been in many such meetings, but she is in this one because the person who is going to read is the agent for her old friend Gunther, who she lost track of in Germany during the war. But when the “agent” begins to speak, she realizes it is Gunther himself, twenty years older. And Gunther believes our protagonist died in the war, and is reading a sort of eulogistic poem about their relationship then. Does she reveal herself to him? Or will events force a reunion willy-nilly?

This is very well written, but I can’t think of it as horror; again, it’s prime dark fantasy. I think maybe Rabinowitz is a person to watch if this is typical of her writing.

“Teen Spirit” by Gary McMahon is good dark fantasy, but not exactly horror—and when I say “horror” I’m not talking about gore or slasher or anything that crude, although those have their place. I define horror as fiction that either gives me a frisson of fear or terror, or involves my deeper emotions on behalf of a character or setting. I recognize that blood, guts and disgusting things have their place in horror, but they do not define the genre.

McMahon’s story fits into the better category—where a widowed mother, Helen, is dealing with a rebellious 14-year-old Todd. His father’s death has left both mother and child with many unresolved issues (a fairly common real-world situation), and she has no idea how to deal with him.

Todd goes out late at night and stays out all hours with his “mates”—and Helen is sure he’s doing some kind of drugs, or at least participating in some kind of illegal activity. She follows him one night, but finds nothing conclusive and indeed, is scared by the area she follows him to, so much that she runs home before even seeing where he ends up.

The ending is not chilling in a traditional sense, but is to Helen, and should be to us as parents, siblings and fellow-travelers—as it hints that the younger generation is even more alien than most adults fear. This one gives a frisson for an entirely different reason, so maybe it does slip across the line into full-fledged horror.

Altogether a well-produced magazine, in my opinion—with one puzzling exception: throughout the first story especially, but spaced liberally throughout the magazine is that godawful neologism “alright”—which really, colloquially speaking, gets on my nut. There is no such word, people—it’s two words: “all” and “right”—my 5th grade English teacher taught us that. If it’s getting so bad that even in the UK people are not learning proper English then Lord help us!

Black Static can be found here.