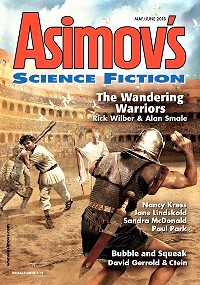

Asimov’s, May/June 2018

Asimov’s, May/June 2018

“The Wandering Warriors” by Rick Wilber and Alan Smale

Reviewed by Alex Clark-McGlenn

The May/June issue of Asimov’s is upon us. Inside are a host of new goodies from which to choose. Full disclosure here, I have a subscription to this magazine, and while this has been a new development (in the last 6 months) it has long been one of my favorite genre magazines. I say this due to the fact that this issue doesn’t quite live up to the standard I have come to expect from Asimov’s. While there are a few stories that did catch my eye in this issue, in prior months it hasn’t been unusual for my mind to be blown multiple times in a single issue. That’s a high bar, but that’s the bar serious fiction sets (and I include genre within the realm of “serious fiction”). Anything less is, not a waste of time (generally speaking, reading is never a waste of time), but at least not as profound an experience as hoped for. With all this being said, don’t be dissuaded from this issue alone. It has some hidden gems.

For those of you familiar with Asimov’s, the title story of this issue will hold a familiar face. Rick Wilber has teamed up with Alan Smale to bring readers another installment of the (mis)adventures of Moe Berg, a historical figure that, apart from playing baseball in the Major and Minor Leagues in the 1930s, served as a spy during World War II. Wilber has published a series of stories about Moe Berg over the years, and in this episode Moe is faced with inexplicable time travel while in Illinois on the road with his baseball team, “The Wandering Warriors.”

The piece is reminiscent of A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, by the great Mark Twain, though by premise only, not by style. Wilber and Smale succeed at a colloquial first-person point-of-view narration, which makes the piece a breeze to read, and while “The Wandering Warriors” doesn’t redefine the time-travel or adventure genres, it’s an exciting and fun romp through time with relatable and interesting characters.

Cadwell Turnbull brings a near-future government think-piece to this issue. In “When The Rains Come Back,” Myron and his 12-year-old daughter Sasha live on an isolated island, run by anarchists. In this world, governments aren’t dependent on place, but by the way in which you interact with others who share your “gov.” This piece succeeds in conveying a complex alternative to our current forms of government with concision. However, the explanation of the world, the interactions of the “govs,” as interesting as they are, come at the expense of much of the plot and most of the tension. While the end sees some kind of change and growth within the characters introduced at the beginning of the piece, it feels haphazard, taped on, rather than woven into the inevitable fabric of the piece.

In “Life from the Sky,” Sue Burke treats readers to an alien invasion that might not be an invasion at all. The whole piece is predicated on the idea that a collection of geode-like fragments have fallen from the sky and washed up on the coast of North America. These rocks float due to vacuum pockets, and the innards are, what appears to be, a strange fractal-like organ system. The thing is, nobody knows.

Really, though, the aliens, or the rocks, or the geodes, or whatever they are (in the story they are called Spaceflakes) don’t have much to do with the deeper meaning of this story.

The main character is a young woman who lives with her mother and works as a freelance event planner. She’s very nice, doesn’t take risks, and doesn’t step on anyone’s toes. What she wants is attention. She wants to make waves in her life. She wants to be noticed. At the same time, her mother has gone off the deep-end with conspiracy theories concerning the “Spaceflakes.” Social media, news, fake news, and alternative facts are ubiquitous, and the narrator’s mother has fallen prey to this misinformation ecosystem. She believes the “Spaceflakes” are markers for an alien invasion.

Then, when the narrator finds a “Spaceflake” on the beach, she ends up garnering a bit more attention than she bargained for. This piece is about how ubiquitous social media and news (real or fake) shapes our identities, and how serious the repercussions can be.

In “Time Enough To Say Goodbye” by Sandra McDonald and Stephen D. Covey, readers are introduced to Lina, a young, pretty Princess Leia at an Orlando SF convention. She chats up a young man who is (predictably dressed like Han Solo). The young man has an uncle who is developing a simulant that acts as an asteroid in the early years of mining precious metals from asteroids. At first, readers are led to believe Lina is interested in the strapping young man, but it’s quickly revealed that Lina is not all she appears to be.

This story utilizes time-travel in an off-hand type of way, but also puts its own twist on the butterfly-effect-meets-time-travel theory. “Time Enough to Say Goodbye,” is about family and loss; about words left unsaid and the truths we wish we could tell the people who mean the most to us.

“Creative Nonfiction” by Paul Park offers a unique take on an old cliche. An adjunct college professor who teaches creative nonfiction finds himself living through the experiences one of his students writes about. While it’s a tried concept, this piece keeps it interesting with enough clever meta-jokes about how fiction and creative nonfiction are supposed to work, that you can’t help but be amused. As the student’s work becomes more and more exaggerated and unbelievable so does the piece. One of the paradoxes of fiction vs. nonfiction is that fiction always has to make sense, and nonfiction doesn’t, because it happened. That’s where this piece falls apart. Since it’s operating on the assumption that nonfiction doesn’t need to make sense, it takes all kinds of liberties that readers of fiction just wouldn’t stand for. While it’s a clever piece, the concept doesn’t make up for its rather clumsy execution and presumption.

“Riverboats, Robots, and Ransom in the Regular Way” by Peter Wood offers up some SF satire. When Maggie goes on a retreat with her co-workers on a galaxy-hopping spaceship, a pirate vessel traps them with a tractor beam. The robot on Maggie’s ship, Chip, is less than helpful, as his concern is protecting the ship itself, noting employees are much less difficult to procure than an interplanetary vessel. Everything the robot does is for the benefit of the company, and even in the midst of a hostage situation, he is still trying to charge the hostages extra fees. When the pirates try to force a ransom out of the corporation, it doesn’t work, and so there is a stalemate. That is, until Maggie and the first mate of the pirates take matters into their own hands.

This is a clever piece, strong in its readability and fun in its allegory. While it doesn’t offer up anything groundbreaking in way of the genre, it’s a piece worth the time.

Nancy Kress’s reputation precedes her in this issue and should be one of the highlighted stories for any reader who enjoys SF answers to contemporary problems. “The Cost of Doing Business,” is about a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who gets the shot of a lifetime—to follow James Sullivan (a Steve Jobs, Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg composite character) and write a book about his next great endeavour. He plans to take the United States of America off petroleum products. To the protagonist, Kayla, this seems impossible, but when a new disease breaks out that is spread by mosquitoes and is connected to anyone who lives by busy freeways, pushing a green political agenda is within Sullivan’s grasp.

Despite the rather condescending tone this piece starts out with (Kayla takes the job reporting on Sullivan because she’s just so tired of writing for The New Yorker), it quickly falls into a readable and interesting flow, willing any reader to find out what happens next. While the ending is one that any rational reader will guess, it’s a fantastic piece that will keep you on the edge of your seat the whole time.

Marc Laidlaw has been writing for years, but recently retired from his career in the gaming industry (working on legendary games like Half-Life and Dota 2). “A Mammoth, So-Called,” is a curious piece, told in an informal manner of one man telling a group of others a story. The narrator is a scientist who was on an expedition when they discovered a mammoth inside a block of ice. In their attempts to bring it back to North America, they experience some interesting issues—and whatever readers think is going to happen is sure to be off the mark. “A Mammoth, So-Called,” is a creative piece that keeps the reader guessing; however, the structure of the piece, once removed, as the narrator is telling his story, is an odd choice. It creates a clear distance between the reader and the first account, and the effects are not desirable due to a lack of tension. When a character is telling other characters a story that has already happened, the stakes of the story melt away unless it can be related back to the immediate present scene. An interesting idea that didn’t quite live up to expectations.

A delightful little story about the infinite possibilities of branching realities is Jane Lindskold’s “Unexpected Flowers.” When an unnamed woman comes home and finds Valentine’s Day flowers on her doorstep, she knows it’s not from her boyfriend—not given the fight they had about getting married that morning. She goes through all the reasons to bring the flowers inside her home. Is he trying to buy her off with flowers? But she can’t tell, for there is no card. Does she have a secret admirer? Or is it just an accident? And this is when the narrative splits into possibilities. Nothing happens for sure, and before long you’ll be caught up in the different potentials of what some misplaced, “Unexpected Flowers” may cause.

The last story in the May/June issue is a bulky novella by David Gerrold and Ctein, entitled “Bubble and Squeak.” “Bubble and Squeak” couldn’t have been published at a more relevant time. It takes place in the present, or near present (give or take 5 years?) Los Angeles. Hu and James are about to go to Hawaii for their honeymoon when the news comes along that there has been a huge Tsunami that has wiped out a bunch of major cities on the Hawaiian Islands. Not only that; the seismic activity has created a second Tsunami that is headed straight for L.A. and the rest of the west coast. What follows is a stressful and thoughtful look at what a full Tsunami evacuation of Los Angeles might look like; the difficulties law enforcement would have and how people would react as a giant wave grows closer. This is a realistic piece in terms of the natural catastrophe, but falls short, or perhaps sacrifices, character development. Instead of meaningful characterization, the protagonists function on gimmicks and tropes. “Bubble and Squeak,” for instance, are the pet names the two characters, James and Hu have given each other, and while this might be a detail that should endear them to readers, the characters continue using these names long after it seems appropriate or realistic. But as everything comes at a price in fiction, this piece has a ton of action at the expense of its characters.

Alex Clark-McGlenn graduated from the Northwest Institute of Literary Arts. His fiction has appeared in a number of literary magazines and anthologies including the Best New Writing 2016 and The Cost of Paper Volumes Three and Four, Smokebox.net, and more. He lives in Olympia, Washington and is seeking representation for his debut novel, a blend of magical realism and horror.