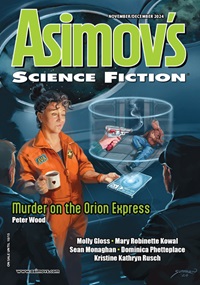

Asimov’s, November/December 2024

Asimov’s, November/December 2024

“Death Benefits” by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

“Wápato” by Molly Gloss

“So Long in Miami” by Garrett Ashley

“Dreamliker” by Dominica Phetteplace

“Mere Flesh” by James Maxey

“The Start of Something Beautiful” by Zack Be

“Murder on the Orion Express” by Peter Wood

“The Ledgers” by Jack Skillingstead

“Deep Space Has the Beat” by Mary Robinette Kowal

“Wildest Skies” by Sean Monaghan

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

With two novellas, two novelettes, and six short stories, this issue supplies fewer works of fiction than usual, but with an adequate variety of themes, settings, and moods.

“Death Benefits” by Kristine Kathryn Rusch is the lead novella. It takes place against a background of multiple planets inhabited by human beings, with nearly constant war going on amongst them. The narrator is a private investigator of sorts, helping people who believe that those they have lost to war are not really dead. He becomes involved with a woman who believes she has seen her lover alive, even though the government reported him killed in battle.

Alternating with the first-person narrative are sections of text dealing with other characters who have lost loved ones during wartime. These do not directly relate to the main plot, and can be thought of as individual short stories sharing a common background. There are also flashbacks to the narrator’s youth, when he endured a similar loss.

This mosaic narrative technique creates a powerful portrait of the emotional devastation suffered by the characters. The main plot is more of a suspense story, and carries less of an impact. The interplanetary background is not necessary, and the same story could take place entirely on Earth during a time of war.

In “Wápato” by Molly Gloss, an elderly woman experiences shifts in time somehow associated with shadowy spirits inhabiting her barn. For example, her dead husband shows up when she needs help with farm chores. Other experiences take her and a friend into the past and future.

This is a quiet, character-driven tale that reads like magic realism. Its fantasy content, although critical, takes up less of the text than descriptions of the protagonist’s daily life. Readers should not expect dramatic events, but rather a slice-of-life with insight into the nature of time.

The narrator of “So Long in Miami” by Garrett Ashley arrives at a research station in order to meet a woman with whom he has an online romantic relationship. He is startled to discover that she altered her image on the computer, threatening their love affair. A crisis at the station may bring them together again.

I have deliberately avoided describing the story’s futuristic background in order to point out that it is not relevant to the plot, even though it makes up most of the text. The setting is Florida at a time when much of the state is underwater. In addition to this, an infestation of bacteria alters the ocean’s ecosystem, and extreme tides cause further damage.

This is an example of the kind of science fiction where the background is more interesting than the story. Certainly, there is nothing futuristic about people creating false personae on the Internet, and the plot could easily take place in modern times.

The novelette “Dreamliker” by Dominica Phetteplace involves a young woman who writes fan fiction, with a great deal of help from artificial intelligence, that wins her an admirer who helps her get an office job. The work involves creating messages to the bereaved, again mostly written by AI, that simulate those that might have come from the deceased. The situation doesn’t work out for her.

The protagonist is a pathetic character, barely supporting herself and her dumpster-diving, shoplifting great aunt through the meager donations she gets from readers of her fan fiction. Her romantic life is also a failure, consisting of a single date that went nowhere. She winds up exactly where she started.

I’m not sure what the author intends with this downbeat story. Perhaps it is meant to satirize things like fiction made by AI and businesses that offer simulated experiences. If so, this is very subtle, and the result is simply an account of a character who fails to take advantage of an opportunity.

One odd aspect of the story is the fact that the billionaire who created the business has two extra thumbs grafted on his hands. This weird detail is out of place in an otherwise realistic, barely futuristic tale.

In “Mere Flesh” by James Maxey, the narrator’s father, more than a century old, has an experimental artificial intelligence system implanted in his brain. The intent is to reverse the effects of Alzheimer’s disease, so that the elderly man is able to recognize people and retain memories. The AI also directs his diet and such, so that he remains as healthy as possible. Despite this help, he eventually requires a live-in nurse for full-time care. When both he and the nurse disappear, the narrator tracks them down and makes an extraordinary discovery.

The plot requires that the initial premise, which involves believable technology of the future, evolve into something much more. This may strain the reader’s suspension of disbelief. One minor aspect of the story, that blood transfusions from the young could help with aging, is highly speculative, and is also difficult to accept as plausible.

“The Start of Something Beautiful” by Zack Be features two artists in lunar orbit with an experienced astronaut. The intent is to have the pair create works from this unique perspective. A crisis forces one of the artists to rescue the astronaut, who is injured during extravehicular activity.

In essence, this is the kind of problem-solving story that often appears in the pages of Analog. The necessity for a character with very little experience to perform heroic actions in space adds some interest to a familiar plot.

As its title implies, the novelette “Murder on the Orion Express” by Peter Wood is a mystery set aboard a starship. Flashbacks reveal the crisis that led to the crew, mostly in stasis during a voyage that will last more than a century, splitting into two opposing parties. The leader of one of the parties disappears, and there is video evidence of his rival killing him. There is, of course, much more to the situation than meets the eye.

Likewise, there is much more to this story than just a whodunit. Much of the plot involves the protagonist’s relationship with a former lover, now older due to spending less time in stasis. Even after the case is solved, there is another threat to the starship.

The plot depends on the fact that the vessel is faster than light, even though the trip will take so long. The method by which this is achieved is the key to the solution to the mystery. I found this unsatisfactory, as the FTL drive involves some handwaving on the author’s part. The threat to the vessel mentioned above also requires some questionable scientific speculation, in the form of a so-called rift in space, without any explanation for its existence being offered.

“The Ledgers” by Jack Skillingstead features a man who records the names of those killed in a war. A stranger follows him. Meanwhile, he comes across the body of a murdered woman, and realizes that there are almost no women in his city. A further encounter with the stranger leads to a strange transformation.

This disjointed synopsis fails to capture the eerie, surreal mood of a mysterious and disturbing story. There seems to be some allegory intended for the way in which war transforms civilians as much as it does those directly involved in battle. Even if this interpretation is correct, much of the work remains enigmatic.

In “Deep Space Has the Beat” by Mary Robinette Kowal, a woman runs a dance club where the floor absorbs the kinetic energy of the gyrating patrons. A potential investor arrives to experience the place, but someone hacks the club’s display system, replacing walls covered with scenes of outer space with pornographic images. The woman has to figure out who is responsible, while keeping the investor from seeing the images.

The premise is unusual and plausible, the plot less so. The mystery of who is responsible for the hacking involves a red herring, and one has to wonder why that character is present at the club at all. Readers might also question the fact that two students from MIT wind up as a dance club owner and a pop music star.

The novella “Wildest Skies” by Sean Monaghan ends the issue. The protagonist is the only survivor of a missile attack from a planet investigated by the crew of his space vessel. The world previously had signs of a technological civilization, but now there are none, making the attack a mystery as well as a disaster.

The main character winds up in the company of the nontechnological aliens who inhabit the planet. They accept him, and lead him on an expedition that ends at a place where he learns the answers to some of his questions. This forces him to ponder his situation, and make a decision that will determine the direction of his life.

The story is notable for the author’s style, which makes use of simple language and short sentences. Paragraphs often consist of a single sentence, and sometimes just a few words. This creates a very fast pace, as the protagonist undergoes many mishaps and adventures, from a crash landing to his final discovery.

The plot is episodic. One sequence, in which the main character is trapped in a deep, smooth bowl, requiring much effort to escape, has little to do with the rest of the story. Readers are likely to find the concluding revelation implausible. The best part of the story may be the unique aliens, who are imaginatively created.

Victoria Silverwolf is currently reading Maps in a Mirror: The Short Fiction of Orson Scott Card.