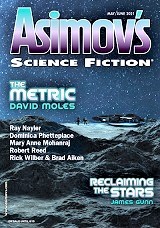

Asimov’s, May/June 2021

Asimov’s, May/June 2021

“The Metric” by David Moles

“Reclaiming the Stars” by James Gunn

“Año Nuevo” by Ray Nayler

“Super Sprouts” by Ian Creasey

“Tin Man” by Rick Wilber & Brad Aiken

“Flattering the Flame” by Robert Reed

“Among the Marithei” by Mary Anne Mohanraj

“Ready Gas and Pills” by Dominica Phetteplace

“The Chartreuse Sky” by K.A. Teryna & Alexander Bachilo

“My Heart is at Capacity” by TJ Berry

“Phosphor’s Circle” by Annika Barranti Klein

Reviewed by Michelle Ristuccia

In “The Metric” by David Moles, an AI occupant on a crash-landed ship brings an urgent message that upends the lives of both those who believe it, and those who don’t: in order to save the future, drastic sacrifices must be made before time runs out. Petal and Piper, young twins, find themselves split by this news and the deadly journey it triggers. Moles brings us into the moment at the right times with vivid descriptions of a world and universe on the brink of a slow death, while at other times zooming further out to feed readers deliciously convincing explanations of theoretical astrophysics. Although the 3rd person narrative tells us little of how characters feel at any given moment, Moles still makes readers feel and sympathize with Petal and Piper for a moving ending. Intelligent diction and brazenly long sentences make for science fiction as hard as a diamond. Moles knows how to push the science fiction envelope without losing accessibility. Quite the deserving opening story for Asimov’s magazine.

“Reclaiming the Stars” by James Gunn follows two robots on an adventure to locate and confront the source of their disturbing hallucinations, an entity that therefore also poses a threat to their budding human nursery designed to replace the lost human race. Unfortunately, the prose comes off as repetitive, causing the story to be dull even as the robots climb mountains and do battle and discuss high science fiction concepts. It seems that every few sentences, readers are reminded in obtuse ways that the main characters are robots that used to be human. In a similar fashion, the robots’ dialogue is anything but sharp and efficient, and the story ends with a monologue from both robots, a vehicle of prose that awkwardly expedites the end while also bludgeoning the reader with the moral of the story. The story risks accidental parody. And the moral of the story? That the older generation (the robots) are destined to become the “monsters” of the newer generation (the new humans), ergo the human children that we have barely seen have no need for the main characters. Having never gained my sympathy for the main characters, the delivery at the end was eye-roll inducing at best. “Reclaiming the Stars” is the final part of a four part series, yet can be read as a stand-alone.

In “Año Nuevo” by Ray Nayler, Bo’s mother attempts to reconnect with a family outing, taking him to the beach to see the enigmatic lifeforms that have become a standard curiosity of Earth life. On the tour, the aliens appear unimpressive, standing there unmoving in the distance like so many trees. When the two sneak off for an up-close view and Bo touches one, we feel his sense of wonder, and the narrative begins to change in subtle ways, not just for Bo, but for anyone who’s been close to these silent, magnificent creatures. Nayler brings us a touching, wondrous story about the every day disconnect between loved ones, from a mother’s guilt to the healing of a teenager’s hurt as he learns how to love the universe and everyone in it more. There’s plenty on the science fiction side that I don’t want to spoil, and with that, we see a timely nod to humanity’s inability to remain cautious, but shown in a touching, positive story that will remain relevant long after. With such moving descriptions, readers will find themselves pausing between scenes to catch their breath.

Ian Creasey brings readers a rollicking comedy in “Super Sprouts,” a novella following the exploits of genetic engineering team and married couple, Harriet and Travis, as they develop kid-friendly vegetables to keep genetic engineering from being voted out as an immoral and dangerous practice. Told from Travis’ pleasantly flippant point of view, Creasey employs just the right mix of first person POV arrogance and romance, drawing readers’ sympathy for the couple’s desire to start a family and keep the freedom of their livelihood, while at the same time poking fun at the opulence of said livelihood and the single-mindedness with which our characters pursue their goals. Wheedling political games and subtle absurdities combine for good laughs. Travis and Harriet also appear in “Ormonde and Chase” (Asimov’s, June 2014) and “The Language of Flowers” (Analog, May 2016).

In “Tin Man” by Rick Wilber & Brad Aiken, readers follow the life history of baseball pitcher Tighe from before the collapse of the USA to the rebuilding of present day Florida. Wilber & Aiken open with a strong scene of Tighe’s first post-apocalyptic baseball game, introducing readers to his mechanical wrist. However, after a strong introduction sequence that takes us back to Tighe’s past, the story drags a bit through a lengthy middle, appearing to bring the main character to Canada for the sole purpose of telling readers that Canada is safe (worthy) and the USA unsafe (crippled by its own hubris), and that rich people have the resources to escape difficult circumstances, which we already saw evidence of in the beginning. This is done in exposition, where readers lack visceral detail of the apocalypse to “show” and convince them of Canada good, USA bad. Likewise, the baseball talk runs thick for a story that is simultaneously portraying big league sports as frivolous, though this certainly verges on personal preference. With rich kid Tighe ditching a career as a doctor for a career in baseball right before the apocalypse, it’s appropriate and in keeping with the theme when the story ends on a note about privilege and marginalized peoples. Despite a few bumps, generally engaging prose overall.

Robert Reed brings readers a solid Great Ship universe story with “Flattering the Flame,” a novella detailing the confrontation between an isolated, warlike alien species named the Flame, and the infinitely more experienced captains of the nomadic Great Ship. When the Flame demand that the Great Ship be theirs, the captains appear to acquiesce. Yet the longer the Flame stay on the ship, the longer they’re exposed to the Great Ship’s menagerie of cultural and technical curiosities, and the more difficult the Flame find it to remain a unified army bent on destruction and subjugation. Reed offers readers a universe with a classically expansive feel, a story decorated with many interesting SF details to absorb and enjoy. The clash of cultures and the actions of individual characters are both fascinating and realistic. The notion of good overwhelming the less good simply by existing and advancing beyond them is certainly a hopeful one, yet it is made complex by the tinge of personal sacrifice, and perhaps a hint of the idea that there are no perfect answers, no perfect outcomes, and no guiltless players. My only issue with the story is an opening that I found strangely disconnected from the rest, a scene that could have used more explanation of setting. Even so, the scene itself is interesting and emotionally relevant to the story, and the next scene brings readers straight to the intriguing premise.

Mary Anne Mohanraj brings readers a tear-jerker in “Among the Marithei,” a narrative examining the affects of a childhood at war on now first-time parent, Sergey, as he takes his newborn daughter to visit the Marithei, the aliens who rescued him and raised him. Mohanraj’s excellent use of backstory places hatred and love side-by-side: the Marithei, the past war, and Sergey’s years of healing, a healing that realistically stretches into the present of the story. And while both the war and Sergey’s rescue were naturally outside of his agency as a character, it is the years of peace and healing with the Marithei that allow him to make a new terrible choice at the Marith Temple gates. Mohanraj achieves a level of connection and empathy that is difficult to pull off in third person perspective. This beautiful story holds nothing back, so brace yourself.

In “Ready Gas and Pills” by Dominica Phetteplace, Kat inspects pharmacies and busts the corrupt ones for using their high tech pill printing machines to print pills on the down low—that is, she intends to bust them, until she comes up against a situation she’s not sure how to handle. Kat’s investigation pits the purpose of government safety regulations against the complex reality of human needs that fall outside the government’s box of rules. I personally found Phetteplace’s primary example of human need a bit too easy to interpret as a political/religious potshot, but it is not unrealistic, and perhaps some readers will sympathize with the girl with “fundie” parents. Kat begins the story assured of her moral place in society and ends with the notion that perhaps the world is more complicated than that, that she may have more to learn. A decent story with an open-ended resolution, it gives readers room to breathe and reflect.

In “The Chartreuse Sky” by K.A. Teryna & Alexander Bachilo, our narrator investigates a missing child case through a Moscow steeped in augmented reality, a technology so common that abstaining from it makes one an incidental social outcast. When augmented reality or the lack thereof ends up having everything to do with the missing child’s safety, our narrator must leave their comfort zone to rescue the child. Teryna & Bachilo’s immersive descriptions make “The Chartreuse Sky” an exciting story about the social inevitability of tech and the dangers of arbitrarily removing an individual’s choice in how or whether to interact with that tech.

TJ Berry’s “My Heart is at Capacity” follows robot Paul as he arranges an upgrade for himself for the sake of his human partner, so he can devote more processing power to assessing her needs. Narrating from Paul’s perspective, TJ Berry expertly twists the dials of reader emotions, explaining Paul’s internal processes (motivations) in such a way that we never forget that he’s not human, yet we feel for him as if he was. As Paul strives to elicit better, more loving reactions out of his partner, some readers may guess what Paul will learn once he upgrades, but this irony makes the story all that more bittersweet. This is a moving story with an ending that questions the meaning of happiness and the definition of a healthy relationship.

In “Phosphor’s Circle” by Annika Barranti Klein, our first person narrator’s new job as tour guide at a zoo leads them to uncover a conspiracy. Many readers will identify with the theme of economic disaster and mistrust of authority, a theme enhanced by the convincingly youthful snark of Klein’s narration. Surprisingly risque, it is unclear whether the main character’s sexual escapades are to be taken as a positive aspect of their self-actualization, or a sign of stress and increased risk taking, building up to the narrator’s actions at the end. This tell-all level of detail might make the narrator a risky character for earning some readers’ sympathy. Regardless, Klein’s use of a common experience—watching animals in a zoo—makes for an interesting what if in this contemporary science short story.

Michelle Ristuccia enjoys slowing down time in the middle of the night to write, read, and review speculative fiction, because sleeping offspring are the best inspiration. Find her on Facebook and twitter @mrsmica.