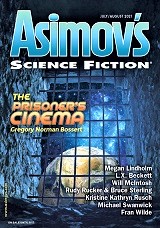

Asimov’s, July/August 2021

Asimov’s, July/August 2021

“The Prisoner’s Cinema” by Gregory Norman Bossert

“Alien Ball” by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

“Philly Killed His Car” by Will McIntosh

“Seed Star” by Fran Wilde

“The Hazmat Sisters” by L. X. Beckett

“Giving Up the Ghost” by Meghan Lindholm

“The Children of the Wind” by Gregory Feeley

“Huginn and Muninn—and What Came After” by Michael Swanwick

“Fibonacci’s Humors” by Rudy Rucker & Bruce Sterling

“Tweak” by Taimur Ahmad

“Out of the Box” by Jay O’Connell

Reviewed by Mike Bickerdike

This issue of Asimov’s contains a novella, 6 novelettes and 4 short stories. The quality of the content was not as high as in some issues, with only one story being highly recommended reading.

“The Prisoner’s Cinema” by Gregory Norman Bossert is an SF story that seemed a good deal longer than its novelette length. In a dystopian future, famous social media agitators and corporate critics are sentenced to prison on an orbital station that also doubles as a continuous reality show for people back on Earth. When a new inmate joins the small cast of prisoners, empty picture frames start to appear on the walls, which the inmates can only ‘fill in’ with their imaginations. While it’s not an uninteresting concept, the story is unfortunately let down by unappealing characters—with which the reader has no connection—leading to a lack of dramatic tension. These problems, coupled with the dense writing style, make the story rather unengaging and by the end, I had lost interest in the mystery of the picture frames and the ultimate outcome.

“Alien Ball” by Kristine Kathryn Rusch is an SF story that explores diversity in sport. An old male basketball announcer is asked to investigate and comment on whether an alien race, the Ashtenga, should be allowed to play in a basketball game with humans. A very thin plot overlays what is basically an historical perspective essay arguing for inclusivity and diversity in professional sport. The aliens under consideration for inclusion in the sport are a rather obvious metaphor for transgender players and other minority individuals. While that’s all very magnanimous, as science fiction there is really no story here, and the social messaging comes across as preachy, overshadowing any fictional elements.

In “Philly Killed His Car” by Will McIntosh, cars, white goods and household gadgets all have AI, and are partially self-governing in their actions. Philly is in debt, and what with his girlfriend having a baby on the way, he needs to obtain funds by selling his car. But his car, Madeleine, doesn’t want to be sold, and keeps nixing the deal. In desperation, Philly and his friend cook up a deal to obtain the insurance on Madeleine, with unforeseen deleterious consequences. This is quite an amusing tale, and it also delivers some tension and depth, taking the control that electronic gadgets have over us to an SF extreme. Overall, it was an engaging novelette, though the ending did not entirely satisfy this reader.

“Seed Star” by Fran Wilde is a rather far-fetched SF short story, in which a ‘Varian’ is granted a ‘fourth-dimension’ pregnancy, while serving on a military space station. Unfortunately, it turns out the pregnancy is not of a Varian embryo, but of a ‘seed star’, that has been implanted at distance into his ‘foldspace’ womb. There is much here that seems to make little sense, including notably, the use of ‘seed star’ technology to prevent stars from dying, given most stars exist for billions of years, and their expiry is sufficiently rare and predictable as to be unlikely to require intervention from sentient races. The station is said to be circling a star cluster, though this doesn’t make astronomical sense. It also seems odd that the pregnant Varian is described as male (if it’s to be assigned a human gender, female would be more appropriate, surely), but is otherwise not described. Indeed, the lack of description and clarity regarding the alien race and the space station, and the ultra-speculative technology and unlikely science prevent greater immersion in the story.

“The Hazmat Sisters” by L. X. Beckett is a dystopian future novelette, set on an Earth struggling with a viral pandemic. Three sisters are travelling by foot to the Great Lakes, trying to avoid danger and attention during what is essentially a futuristic civil war. To help them maintain morale and due care, their mum, with whom they are travelling, gives them ‘XP’ at the end of each day, in the manner of a role-playing game. The winner of the most XP once they get to their destination will be granted a wish. The idea is quite intriguing and the tech in the story, such as app-controlled clothing, is imaginative, providing quite an immersive imagined world. On a less positive note, however, the story’s plot is not as strong as the world-building, with the conclusion lacking the bite it might have had, given the promising set up.

“Giving Up the Ghost” by Meghan Lindholm is a short fantasy story about a ghost dog who turns up at a pet boarding shop to get the attention of the owner. The story evolves into a bit of a ‘whodunnit’. Characterisation is rather good, which helps to build tension and an emotional response to the dramatic situation as it unfolds. Overall, it’s quite an enjoyable ghost story that will probably appeal particularly to dog lovers.

The novelette “The Children of the Wind” by Gregory Feeley starts the way an increasing number of modern SF stories seem to start, by dropping into the middle of the story without explanation, leaving the reader somewhat clueless as to what is going on for several pages. The story is set on an asteroid-based spaceship travelling to Neptune from Earth. There is currently unrest between some younger people on the ship and those in control, for reasons that are not fully explained. It is also not made clear what is at stake or who we should root for. Scenes skip around, perhaps in time, perhaps only by place, involving characters who are not described regarding their role or relations. The overall impression is of rather a challenging story that struggles to appeal.

“Huginn and Muninn—and What Came After” by Michael Swanwick is prefaced with a warning that it deals frankly with suicide and despair. This is a fantasy tale that explores existential realities and the control of one’s destiny. Huginn and Muninn of the title are vultures that the protagonist, Alyssa, imagines perch on each of her shoulders, as symbols of her despair with the world. Alyssa finds one morning that she can pass straight through her mirror to a quite different world, where time travels backwards, all is opposite, and the vultures are real. Moreover, travellers from one world to the other switch gender when they cross-over. This particular effect allows the characters to indulge in ‘gender fluid’ sexual experiences, which is very on-trend, of course. Readers who like layered stories full of strange mystery and which only slowly reveal the story’s truth, may well enjoy the tale, which is quite rich in ideas. However, if you like your fiction uplifting you won’t find that here. The characters and dream-like unreality didn’t especially appeal to me, though the final few paragraphs, despite being very grim, almost saved it.

The novelette “Fibonacci’s Humors” by Rudy Rucker & Bruce Sterling, set in a post-dystopian future, explores a highly unusual technological concept. Gene editing advances have enabled the development of self-aware slime molds with incredibly complex neural nets, that can operate as mobile phones and computers. The idea sounds rather daft and unlikely, but it’s told in a light and engaging way and just about gets away with it. The story centres on a married tech-savvy hippy couple; the man is obsessed with the medieval arithmetician Fibonacci, especially regarding his theories on the use of the ‘humors’ as a calculating tool to predict human responses in detail. His wife has an especially intelligent and advanced slime mold called Cee Cee, and she can sell buds from the creature to interested buyers. There are quite a few threads to this tale, including a blockchain cryptocurrency scam, that will likely appeal to fans of cyberpunk—an SF sub-genre for which Rucker and Sterling are well known. Cyberpunk is not a sub-genre that particularly appeals to me personally, but this was quite good fun, despite being more than a bit mad.

“Tweak” by Taimur Ahmad is a thought-provoking, superior short story, in which people’s memories can be changed in specialist clinics to ‘improve’ them. Amin decides to tweak his memories artificially in this way, to optimise how certain important scenes in his life seemed to have played out for him. He inevitably tweaks his memories so that he recalls acting more heroically than occurred in real life, but he doesn’t consider the consequences of his actions. It’s an intriguing plot, cleverly developed by Ahmad. The story explores two ideas: firstly, that while our memories may belong to us as individuals, they impact others and we actually share in their value; and secondly, that who we are is an aggregate of our memories. Highly recommended, this is the finest story in this issue of Asimov’s.

“Out of the Box” by Jay O’Connell is a near future SF novella, in which a technology genius and college dropout invents a replication device in her basement. The potential fallout, economically and socially, from such an important and life-changing invention is not lost on the inventor, Nayla, or her friend Carlos. However, their worry over the harm that could result from misuse of the device is overtaken by more immediate and personal danger from mysterious agencies within the authoritarian regime that governs their lives. A lot occurs in this story, but rather challengingly, little is really explained as the tale progresses. The ultimate goal of Nayla, the nature of the government, the reasons for her inventions and so forth, are not clearly described, leaving the reader without an obvious outcome for which to root. Thirty pages in I was unsure if I wanted Nayla to win through or lose out. Lose I think—my sympathies never lay with the protagonist—which I doubt was the author’s intention. Ultimately, the end result was a novella that failed to engage.

More of Mike Bickerdike’s reviews and thoughts on science-fiction can be found at https://starfarersf.nicepage.io/