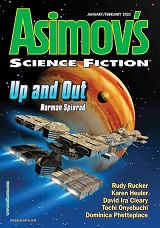

Asimov’s, January/February 2023

Asimov’s, January/February 2023

“Up and Out” by Norman Spinrad

“Alien Housing” by Karen Heuler

“Woman of the River” by Genevieve Williams

“The Roots in the Box and the Roots in the Bones” by T. K. Rex

“Cigarettes and Coffee” by Ramsey Shehadeh

“Jamais Vue” by Tochi Onyebuchi

“The Less than Divine Invasion” by Peter Wood

“Tooniverse Telemarketer” by Rudy Rucker

“What We Call Science, They Call Treason” by Dominica Phetteplace

“My Year as a Boy” by David Ira Cleary

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

Two novellas serve as bookends for the magazine, with a pair of novelettes and half a dozen short stories between them.

In the lead novella “Up and Out” by veteran author Norman Spinrad, the narrator looks back on his life as a wealthy entrepreneur. His economic skills brought a breathable atmosphere to Mars and funded the development of human hibernation that allows for long-term voyages in space.

The narrator ponders whether to go into hibernation in order to await the arrival of an alien vessel, expected to reach Earth in a millennium, or to use the same technology to make a journey to the stars that will last for many thousands of years. Much of the story also deals with his relationship with a reporter, who is both lover and promoter.

The author makes use of many concepts from space travel fiction, and the resulting work seems like a cry of encouragement for humanity to venture out into the universe. One questionable aspect of the story is the fact that the narrator renames himself Elon Tesla. Because the author openly labels his creation an homage to Elon Musk, this is hardly a minor detail. Whatever one might think about that billionaire (and recent events have made his name more controversial than when the author wrote the story, given the time required for publication), it draws the reader out of the work and into the modern world, lessening its appeal.

The protagonist of “Alien Housing” by Karen Heuler works for extraterrestrials who arrived on Earth with their youngsters. Her job is to watch over the mischievous, shape-shifting adolescents. After a while, she discovers the real reason the aliens are here.

The author creates interesting extraterrestrials, and manages to make them seem truly alien. The protagonist’s relationship with her employer is intriguingly ambiguous. Readers may be able to predict the ending.

“Woman of the River” by Genevieve Williams takes place at a future time when people are working to restore the damage done by climate change. In particular, residents of the Seattle area act together to heal their waterways.

There is not much plot to this futuristic slice-of-life. The only conflict is a disagreement about what exactly should be done about the local river. The story is beautifully written, with a great deal of vivid sensory detail about the area’s ecology. Fans of so-called solarpunk or hopepunk are likely to appreciate this quiet portrait of a place the author obviously knows and loves.

In “The Roots in the Box and the Roots in the Bones” by T. K. Rex, people are confined to cities, with wilderness areas forbidden to them. Rangers accompanied by drones patrol the area, which supplies food for the city dwellers. The plot deals with the search for a missing person in the wilderness, leading to the discovery of an extraordinary transformation.

The story requires quite a bit of effort on the part of the reader, as much of its content is hard to understand without exposition later in the text. Adding to the difficulty is the fact that the narrative unexpectedly turns into a lengthy flashback concerning a secondary character late in the story. These techniques give a novelette the complexity of a novel. The transformation mentioned above is a striking one, and may be enough of a reward for patient readers.

“Cigarettes and Coffee” by Ramsey Shehadeh takes place in a future United States of constant surveillance by the government. After multiple attacks on surveillance equipment in a small Texas town, federal agents sent an advanced robot to investigate the crimes. The local sheriff has other ideas.

As its title might suggest, the story has the informal style and cynical mood of a hardboiled crime yarn. The way the sheriff and his confederates deal with the robot is cleverly plotted. The speculative content is plausible, and the characters and setting are realistically portrayed.

“Jamais Vue” by Tochi Onyebuchi is narrated by an artificial intelligence that repairs the memories of people who have suffered brain damage. Through its work with two people the reader learns of their relationship.

The unusual choice of narrator, combined with disturbing aspects of the plot, give this work the feeling of a horror story. This is due not only to scenes of violence done by humans, but also because of the clinical detachment of the narrator, as it literally reaches into the brains of its clients. Readers in search of a dark tale told in a nearly emotionless style will best appreciate this chiller.

In sharp contrast to the preceding story, “The Less than Divine Invasion” by Peter Wood is a wacky comedy that spoofs familiar themes from science fiction. Humanoid aliens are on Earth in preparation for taking over the planet. That seems to be the idea, anyway, although the extraterrestrial agents on the planet spend most of their time dealing with paperwork and leading ordinary lives.

The protagonist is an alien who becomes jaded with the long-delayed invasion, and just wants to run a hamburger stand instead. Meanwhile, his fellow aliens operate a movie theater that runs old science fiction films. The trio become involved with an agent of a government organization dealing with aliens, and a lawyer who convinces the burger flipper to run for mayor.

This is a silly story, obviously, which should amuse SF fans with its references to old movies, flying saucers, and Roswell. There is also a touch of satire of both human and alien politics. At novelette length, it drags the joke out a little too long, but should raise smiles from readers.

“Tooniverse Telemarketer” by Rudy Rucker involves a disease that is caused by sounds from subspace, a dog possessed by an alien, an artificial intelligence in the shape of a doghouse, cartoon characters, an alien telemarketer, and much more. Any attempt to otherwise describe the plot of this frenzied farce is doomed to failure.

The author’s wild imagination and tendency to throw in everything but the kitchen sink are at full strength here, leaving the reader breathless. It may be a matter of taste as to whether the result is a delightful romp or meaningless chaos.

In “What We Call Science, They Call Treason” by Dominica Phetteplace, a billionaire offers the narrator a device that changes color in response to one’s emotional state. (It’s pretty much a mood ring that actually works accurately.) This is just the start, as the rich man turns out to be from an alternate universe where Rome never fell.

The good news is that he can bring advanced technology from that reality to our own, although that’s a crime carrying the death penalty. The bad news is that parallel Earth is about to be destroyed by an approaching asteroid.

Much more happens in the story, none of which I found plausible for a moment. Although not openly comic, the work is definitely tongue-in-cheek. Major threats, such as the asteroid and the death penalty, are dealt with in a few words. Readers who don’t demand believability are likely to enjoy it.

Finishing the issue is the novella “My Year as a Boy” by David Ira Cleary. A sexless clone who has just entered early adulthood decides to be male. He takes a trip on an airship, trying to figure out how to be masculine along the way. At his side is his loyal robot servant, always available to help his clueless master out of his misadventures.

If that sounds familiar, it’s because the author acknowledges the influence of P. G. Wodehouse; the young man and the robot are futuristic versions of Bertie Wooster and Jeeves. Many incidents occur during the voyage, but there is no central plot. The tone is appropriately light, and the work as a whole can be thought of as a way to cleanse the palate after reading more substantial works.

Victoria Silverwolf finished this review on the eve of a holiday that shall remain nameless.