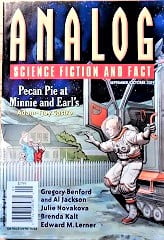

Analog, September/October 2019

Analog, September/October 2019

“The Gorilla in a Tutu Principle or, Pecan Pie at Minnie and Earl’s” by Adam-Troy Castro

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

The latest issue of this venerable publication generously offers a full-length novella, four novelettes, and no less than fifteen short stories, ensuring a wide variety of fiction to enjoy.

Leading off the magazine is “The Gorilla in a Tutu Principle or, Pecan Pie at Minnie and Earl’s” by Adam-Troy Castro. This is one of a series of stories set at a time when an extensive lunar colony is under construction. Readers should not expect hard science fiction, however.

In this strange future, an elderly couple live on the Moon in an ordinary home, without any need for protection from the lunar environment. There is no explanation for this miraculous phenomenon. The narrator speculates that they may be technologically advanced aliens who choose to appear as normal human beings, but makes it clear that this hypothesis is not to be taken seriously.

The couple welcome all who come to their door, with homemade food and friendly advice. The narrator visits them after seeing two men, one fat and one thin, trying to haul a large crate up a lunar hill, while wearing bowler hats and neckties over their spacesuits.

Fans of old-time comedy movies will immediately recognize the pair as Laurel and Hardy, their hapless struggle taken from the award-winning short film The Music Box. The narrator continues to encounter them, acting out routines from their movies on the surface of the Moon. Just like the older couple, there is no rational explanation for their presence. The narrator considers the possibility that they are extraterrestrials, but rejects it and accepts them for what they appear to be.

This is a whimsical tale, not quite a comedy, which is likely to raise a smile. The lighthearted mood is difficult to sustain for an entire novella, especially because there is really no suspense. The narrator simply tells readers what happened, and allows them to make of it what they will. It will appeal most to those who don’t mind a touch of fantasy in their science fiction.

The protagonist of “Awakening in the Anteroom of Heaven” by Brenda Kalt is a reptilian alien, whose people have just been defeated in a war with humans. With the permission of the conquerors, he removes statues of heroic figures of his kind from a sanctuary, in order to transport them to a world where humans do not go. It turns out that the statues are much more than simply works of art.

The author reveals the alien’s true intentions early in the story, making the rest of it anticlimactic. Although the alien culture is interesting, the story ends too quickly, just when dramatic events are about to occur.

In “On Her Shoulders” by Martin L. Shoemaker, a graduate student in astronomy discovers evidence that an object near the orbit of Jupiter is of extraterrestrial origin. Signals from the object reveal that it contains aliens in suspended animation, awaiting rescue by the inhabitants of the star system where they have arrived. The student goes on to win her doctorate, becomes a media star, and has to convince the government to send astronauts to the object.

Despite the extraordinary events in the plot, this is really an introspective story, concentrating on the relationship between the student and her mentor. The characters come to life, and their interactions paint a convincing picture of the way that science really works.

“Paradise Unbound” by Edward M. Lerner takes place on a planet settled by humans in the distant past. An asteroid is about to strike the colony world, threatening to wipe out its inhabitants. The unexpected arrival of a starship offers hope for survival, but brings challenges of its own.

Because this is part of a series, the author fills in the backstory with long, italicized flashbacks. These interrupt the narrative, are unnecessary for those who have read the previous stories, and confusing for those who have not.

The title of “The Swarm” by Mario Milosevic refers to a fleet of ten thousand tiny space probes sent to Alpha Centauri. The vast majority are expected to fail, but the narrator hopes a few will survive to broadcast images of the star system to Earth. Because the voyage will take nearly a century, the narrator decides to go into suspended animation, waiting on Earth, in order to see the results. Her partner, at first reluctant to join her, at last agrees to do the same. What happens when they are revived reveals something about their relationship. This brief tale is more effective as a character study than as a story of space exploration.

“The Annual Argument at the De-Extinction Board Meeting” by Antha Ann Adkins is a very short story about a debate over which vanished species to bring back to life via genetic engineering. One person always wants to revive Neanderthals, but this year suggests the Irish elk. The reason for this involves a subtle ploy on her part. The author displays profound knowledge of biology in what is otherwise a trivial anecdote.

Just as short is “Personalized People” by Norman Spinrad. At a future time when parents choose the genetic characteristics of their offspring, a problem arises when a couple disagrees about what their child should be. The solution is simple and logical. Although elegantly written, this is a minor piece from an author who has been published for well over half a century.

In “The Waters of a New World” by Jennifer R. Povey, colonists on a distant planet face the problem of an organism that makes the local water toxic. The reason for its existence is alarming. Although the puzzle is intriguing, the way in which the organism is defeated strains credibility.

“News from an Alien World” by Sean Vivier involves the decoding of alien signals. They turn out to be the equivalent of human news broadcasts, and reveal a civilization in crisis. Paralleling this discovery is the personal life of the protagonist, as his family breaks up. A similar theme appears in the fact that the main character is the Japanese-born descendant of an American, never quite fitting into his native land.

The author manages to blend all these elements into a unified whole. Although the story does not offer a happy ending, it provides a bit of hope in the fact that the aliens and the protagonist survive their disasters, and will find new ways to live under greatly changed circumstances.

“A Family Rendezvous” by Brendan DuBois takes place aboard a space shuttle unsuccessfully attempting to dock with a space station. A series of unlucky circumstances doom the passengers to die in space if the procedure fails. The narrator, a retired Air Force officer on his first voyage into space, has to go through dangerous extravehicular activities to save himself and the others. The hero is appealing, but the situation is a bit contrived.

The narrator of “From So Complex a Beginning” by Julie Novakova journeys to a distant world to determine if life on the planet evolved naturally or was designed by extraterrestrials. If the latter, this would be the first evidence of an advanced alien civilization. She does not actually land on the planet, but projects her consciousness into an artificial body on the world, in a manner similar to Poul Anderson’s classic story “Call Me Joe” or the movie Avatar. Complicating matters is the fact that someone doesn’t want the truth to be discovered, and that her life may be in danger.

The author combines a scientific mystery with a whodunit in an interesting way, even if the story is sometimes melodramatic. It’s hard to believe that the discovery of advanced aliens would discourage human space exploration, and this is a critical part of the plot.

“Conventional Powers” by Christopher L. Bennett is one of a series of stories about enhanced humans who serve as peacekeepers in a heavily populated asteroid belt. In all ways, these people act as superheroes, taking on new names, special costumes, and so on. This tale takes place at a convention of the peacekeepers, where new heroes are recruited and fans mingle with their favorites. A group of fanatics who insist that only genetic modifications, and not technological ones, are acceptable gets their hands on a device that deactivates the enhancements they oppose, leading to a battle between the Good Guys and the Bad Guys.

The author manages to come up with a plausible way in which superheroes might exist. The peacekeeper convention, obviously based on a science fiction convention, makes the story too much of an in-joke for the average reader. (The conflict at the convention may reflect certain recent controversies within the world of science fiction fandom, although I am not sure if this is the author’s intent.) The frequent references to the sex lives of the superheroes seems out of place.

“A Square of Flesh, A Cube of Steel” by Phoebe Barton features a transgendered protagonist. For medical reasons, she is unable to transform herself completely into what she thinks of as her true self. She currently lives on a colony world inhabited by people who have been bred to be giants. One such huge person is her lover. Her mother comes to take her back to their native world. Because she is still a minor, she does not have the legal right to remain with the one she loves. A desperate attempt to escape leads to a moral crisis, as she must choose between freedom and saving the life of another.

As this brief and overly simple synopsis makes clear, this is a complex story, full of multiple science fiction elements. The author manages to make everything clear to the reader, but the disparate plot points do not always fit together gracefully. The way in which the story ends is difficult to believe.

“Shut-Ins” by Christian Monson is a very short story about two young people, born from frozen embryos on a generation ship and raised by machines, who face the choice of staying inside the environment they know or leaving it to begin new lives on an alien world. This brief tale creates a pair of fully developed characters in a few words, and raises provocative questions about subjects that most science fiction stories take for granted.

“I Dreamed You Were a Spaceship” by Ron Collins is less of a story and more of a prose poem, with a title that reveals its content. There are hints that the subject of the narrator’s dreams is really in a nursing home, with a failing memory. Inevitably, one thinks of Rachel Swirsky’s award-winning, controversial work “If You Were a Dinosaur, My Love” while reading this piece, so much like it in length, content, and structure. Many readers will see it as mainstream fiction, with no real speculative content. Its emotional appeal would be more powerful if Swirksy had not already explored similar use of science fiction metaphors.

Three generations of a family appear in “The Singing City” by Michael F. Flynn. The eldest is a retired astronaut, one of many who saved the world from asteroids programmed by ancient aliens to crash into the Earth when humans reached them. His son leads a much more sedate life as a teacher. His own child is about to leave on a voyage to the outer solar system that will keep him away for years.

This is a sophisticated story, balancing a number of futuristic elements with a clear and elegant style. All of the characters are three-dimensional, and their relationships are as real as our own.

The title of “Astroboy and Wind” by Joe M. McDermott contains the names of its two main characters. They are employed as construction workers, building the shields that protect the inhabitants of a colony world from the environment. The death of a fellow worker leads to a conflict with their employer, and a change in their relationship.

Unlike most science fiction stories, this one deals with blue-collar workers, which makes for a refreshing change of pace and a sense of realism. On the other hand, the same plot could take place among modern construction workers, laboring at the top of a skyscraper, without the need for speculative content.

Because the characters in “Molecular Rage” by Marie Bilodeau have names like Stan and Lisa, the reader assumes they are people. In fact, they are insect-like beings, and no humans appear in the story. The plot begins when Stan is late to work, due to an unexpected delay in the teleportation system that he uses for commuting. Because his job involves scheduling the system, he investigates the cause of such delays. They turn out to involve a secretive military installation, and the deadly energy source the army is trying to keep under control. Meanwhile, Stan’s mate kicks him out of their nest. His only companion is one of his many offspring, who is something of a misfit.

This is a very strange story, both in its inhuman characters and in the bizarre way the teleportation system works. The author certainly shows great imagination, but many aspects of the crisis that drives the plot are unintelligible. The characters are biologically very different from human beings, yet have many of the same emotions, which seems unlikely.

The protagonist of “Trespass” by Tony Ballantyne is a mercenary, hired to track down an old acquaintance who obtains dangerous alien technology. The device, worn like a suit, allows him to journey instantaneously to any place he can see. (As the narrator says, it’s pretty much the science fiction equivalent of seven-league boots.) A battle between the man and his former associates leads to the death of innocent bystanders, making it vital to stop him.

The background of this story is more interesting than its standard action/adventure plot. This is a future of super-advanced technology, much of it taken from a vanished species of aliens. An intriguing aspect of the setting is the existence of a Classical Zone, where only technology that makes use of standard physics, instead of weird alien science, is allowed. The story begins with an artificial intelligence within a humanoid body made out of intricately carved wood. This is a striking image, but irrelevant to the plot.

Finishing the issue is “Road Veterinarian” by Guy Stewart. It takes place at a near future time when the United States and Canada are enemies, existing in an uneasy state of truce. A biologically enhanced military officer kidnaps a veterinarian. The soldier needs the vet to control a genetically engineered organism designed to be a living road surface. Hungry for iron, it escapes and is about to cross the border into Canada, which could lead to war.

Although the story is never openly comic, the author obviously has tongue firmly in cheek. Much of the plot deals with the relationship between the officer and the veterinarian, and almost reads like a romantic comedy. It’s hard to accept the premise of a living chunk of road wandering off in search of iron, but the story is a pleasant enough thing to read, if you don’t take it too seriously.

Victoria Silverwolf notes that the cover of the magazine does not list the full title of the lead novella, probably due to space restrictions.