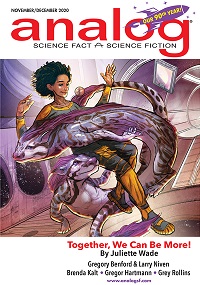

Analog, November/December 2020

Analog, November/December 2020

“Call Him Lord” by Gordon R. Dickson (reprint, not reviewed)

“Together, We Can Be More!” by Juliette Wade

“This Hard World of Unwanted Beauty” by Evan Marcroft

“A Purpose for Stars” by Brad McNaughton

“Ghost Strike” by Brenda Kalt

“Peaceweaver” by Marissa Lingen

“The Polar Bear Sleeps On” by M. Bennardo

“Event” by Timons Esaias

“Courtship FTL” by Mary E. Lowd

“Beloved Toiler” by George Zebrowski

“Brought Near to Beast” by Gregor Hartmann

“Trial and Error” by Grey Rollins

“Asleep Was the Ship” by Eric Del Carlo

“State of Grace” by Clancy Weeks

“Lazarus, Unbound” by Liam Hogan

“Ashes” by Mario Milosevic

“Why Things Work on a Starship” by Stephen R. Loftus-Mercer

“Winter’s Spring” by A.P. Hawkins

“Enter the Fungicene” by J.M. Swenson

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

Many of the stories in this issue deal with interstellar travel and encounters with aliens. Others are set on Earth, or in the Solar System, in futures near and far. As a bonus, the magazine features a Nebula-winning novelette from 1966.

“Together, We Can Be More!” by Juliette Wade takes place aboard a space station containing several species of aliens, as well as humans. After multiple sections of narrative told from the point of view of the aliens, the plot begins with the unexpected arrival of a starship of unknown origin. The inhabitants of the station must work together to avoid a crisis.

The most interesting part of the story is the depiction of many different extraterrestrials. The main plot takes up only the last third of the narrative, so readers must be patient as they are introduced to the aliens one by one. The tale’s theme, that the whole is often greater than the sum of the parts, is a worthy one, but might have been presented in a less leisurely fashion.

In “This Hard World of Unwanted Beauty” by Evan Marcroft, the survivors of a starship’s crash landing on a hostile planet live in an uneasy relationship with the world’s inhabitants. In exchange for time spent attached to the bodies of the aliens, the humans receive the basic necessities of life. (In a gruesome touch, their main source of food is the flesh of dead aliens.) A pair of survivors makes a dangerous trek through the planet’s deadly wilderness to reach another part of the broken starship. Their journey leads to a surprising revelation about the aliens.

The author creates truly bizarre aliens, unlike anything I’ve ever seen in science fiction. The bulk of the story is a grim tale of survival, so a sudden change of mood near the end may seem jarring to some readers.

The protagonist of “A Purpose for Stars” by Brad McNaughton is a human surgeon on an alien planet. The extraterrestrials use changes in the colors displayed on their skins as a form of communication. Those born without this ability are treated as pariahs. The surgeon is able to cure the defect in most of those who suffer from it. A mother presents a child afflicted in this way, but an additional heart problem means that the boy is unlikely to survive surgery. The surgeon’s decision leads to a greater understanding of the aliens, and of his own quest to have a purpose in life.

The story has strong emotional impact without becoming sentimental. The surgeon’s dilemma has no easy answer, and leads to an ending that does not violate the premise of the plot. It also offers insight into the main character’s personality and need to find a reason for his existence.

“Ghost Strike” by Brenda Kalt features a down-on-his-luck asteroid miner reduced to working a menial job on Mars. He accepts an assignment to retrieve unclaimed ore from the asteroid belt, in exchange for wiping out his debts. Instead, he discovers a derelict spaceship, far more valuable than any ore. His struggle to retrieve the vessel involves many dangers. Meanwhile, time is running out on his limited supply of oxygen.

The author creates a realistic character with whom the reader can empathize, particularly during his setbacks and sufferings. Working in space is presented as a dirty, hazardous business, which is more believable than many depictions of it. Certain aspects of the resolution may strike some readers as implausible.

In “Peaceweaver” by Marissa Lingen, a human composer travels to an alien world as a form of cultural exchange. Ironically, the extraterrestrials have no understanding of music at all. In a similar way, the composer finds it difficult to comprehend the way in which the aliens make scents into art. Although the two species cannot fully appreciate each other’s works, they share similar attitudes to the creative process in general. This is a pleasant little fable, best appreciated by writers and other artists, particularly in the way that it deals with the act of criticism.

“The Polar Bear Sleeps On” by M. Bennardo takes place not long after a plague destroyed humanity. The title character leaves an abandoned zoo and enters a house full of dead people, surviving on the food it finds there.

That’s really all that happens in this story. Much of the narrative consists of explaining the situation, and listing things that the polar bear cannot do, because it’s just an animal. The tale consists of sections numbered backwards from five to one, but there seems little point to this inverted structure, as the situation is an inherently static one.

Well under two hundred words long, “Event” by Timons Esaias tells how an undescribed thing fell through the sky, unobserved by human beings but recorded by their devices. The point of this tiny tale seems to be the way in which people disregard important matters and instead concentrate on ordinary affairs. In any case, it can serve as a tribute to automated technology.

In “Courtship FTL” by Mary E. Lowd, a woman shops for a personal starship, and has to convince the sentient vessel of her choice that she would be a proper partner. This very brief story has a lighthearted mood, and is best suited for youngsters. Older readers are likely to find it too cute for their tastes.

“Beloved Toiler” by George Zebrowski deals with William Randolph Hearst’s anger at the way he was caricatured in the Orson Welles film Citizen Kane. As a form of revenge, the millionaire takes possession of excised footage from the director’s next film, The Magnificent Ambersons, leaving only a badly reedited version remaining, distorting the creator’s vision. In the near future, technology allows a restorer to produce a recreated version of what Welles intended, based on the original script. A visit from a mysterious stranger, claiming to possess the missing footage, leads to a change in plans.

About halfway through the story, the reader learns that the narrator is a simulated version of Welles himself. This adds to the theme of reality and illusion, originals and duplicates. The best audience for this unusual tale would consist of old movie buffs. Others may not find it as interesting.

In “Brought Near to Beast” by Gregor Hartmann, genetically and biotechnologically advanced humans have changed Earth in drastic ways, ruling over ordinary people as a distant, almost incomprehensible aristocracy. The main character is a veterinarian, working on the mammoths recreated by his enhanced employers. Unlike the highly educated protagonist, his assistant is an ignorant, superstitious man, although wise in the ways of nature. An unexpected visit from one of the enhanced humans leads to involvement in the dangerous politics of the rulers, and sudden violence.

The background is intriguing, and details of life in the wilderness are vivid and convincing. The last line of the story, although it provides a touch of dark irony, comes as something of a disappointment.

The narrator of “Trial and Error” by Grey Rollins is a cook aboard a starship. Before the story begins, he was imprisoned by aliens, who determined that he was one of the few persons able to consider all aspects of a problem and come up with the best solution. When contact with different aliens leads to bloody conflict, the cook has to use his special skills to defuse the situation.

Like other works in this issue, the best thing about this story is its imaginative depiction of aliens. The cook’s background, although not without interest, is not really necessary for the rest of the plot.

The main character in “Asleep Was the Ship” by Eric Del Carlo is the only human aboard a starship carrying hibernating aliens. To perform a religious ceremony at a certain place in space, the aliens must travel through a region they cannot tolerate while awake. The man’s job is to be a passive caretaker aboard the automated vessel. He finds a young human stowaway on the ship. Because the amount of human food carried by the starship is limited, they face the possibility of starvation. The man also has to wonder if the boy is only a product of his imagination.

The story creates a great deal of suspense, even if the situation is contrived. The man’s mourning for his lover, killed in an accident, adds a touch of pathos, although it verges on sentimentality.

Another starship carrying hibernating passengers appears in “State of Grace” by Clancy Weeks, although this one is full of human beings. A serious breakdown in the ship’s propulsion system, followed by the loss of repair drones, forces the vessel’s artificial intelligence to wake one of the passengers. His job will be to fix the problem manually, although this will expose him to radiation that will cause him to die of cancer before the ship reaches its destination. During the time that remains before he must make the repair, he develops a friendship with the AI, whom he associates with Grace Kelly in the movie Rear Window.

The relationship between the man and the all-too-human AI is a poignant one. An unexpected discovery near the end of the voyage adds a touch of irony. Given George Zebrowski’s story, the magazine might be seen to be providing a special classic cinema issue. Unlike the previous tale, however, in which an old movie is the center of the plot, the presence of Hitchcock’s thriller is peripheral, and somewhat detracts from the story’s appeal.

“Lazarus, Unbound” by Liam Hogan is a very short account of a man put into hibernation aboard a starship that failed before it even left the Solar System. Thousands of years later, he is revived into a world evolved far beyond his understanding. The narrator, one of the nearly immortal, highly advanced persons of this time, describes meeting him, and learns the real reason why the AI that governs their society woke those of his kind.

The main appeal of this brief work is the way in which it evokes vast amounts of time, even though we are given only hints of what this strange future is like. More of a mood piece than a fully developed story, it is likely to fire the reader’s imagination, even if it leaves much unsaid.

“Ashes” by Mario Milosevic is another story that deals with long periods of time in a short space. The narrator is descended from many generations of people bred for longevity. Although the women can survive for nearly a millennium, the men rarely reach a century. The narrator looks back on the deaths of her parents, and anticipates her own child, yet to be born.

As with the previous story, there is little plot beyond the basic premise. The point seems to be that life and death are eternal verities, no matter how they might change. The theme is a profound one, if not entirely original.

“Why Things Work on a Starship” by Stephen R. Loftus-Mercer consists of a conversation between a gifted spaceship engineer and her superior officer. He explains why her brilliant innovations could confuse lesser minds, leading to disaster. More of a fictionalized philosophical essay than a story, this brief dialogue helps the reader appreciate the fact that geniuses need to value the importance of those with only modest skills.

“Winter’s Spring” by A.P. Hawkins features a small team of scientists laboring to set up a colony for a starship full of hibernating passengers. The planet is an extremely cold one, so the situation presents difficult technical problems. Adding to the challenge are tensions among the members of the team.

In essence, this is an old-fashioned problem-solving story, of the kind often found in the pages of Astounding. The solution is a plausible one, although one might wonder why the team didn’t think of it sooner. The relationships among the scientists, whether bickering or developing romances, seem more adolescent than their intellectual skills might suggest.

“Enter the Fungicene” by J.M. Swenson takes place on Earth in the far future. The environment has changed radically, leaving only a few sheltered places where people can survive. Humanity consists entirely of cloned women, many generations after their originals died. These few women are greatly enhanced with biotechnology and neurological implants, which allow them to access the memories of previous clones. Over thousands of years, they have fought to return the environment to a livable state, with little success. One of the women discovers a new lifeform, leading to a change in the way she imagines the future.

The author shows much creative imagination, whether describing a world dominated by gigantic fungi or entering the memories of older clones. The plot offers a sweeping vista of evolution, with a semi-mystical vision of what might follow humanity.

Victoria Silverwolf notes that this issue also contains a scathing political editorial that is sure to generate controversy.