“The Last Days of Good People” by A.T. Sayre

“Great Martian Railways” by Hûw Steer

“Vouch For Me” by Greg Egan

“The Funeral” by Thoraiya Dyer

“We Maintain the Moons” by Lyndsey Croat

“As Time Goes By” by Cam Marsollier

“The Book of Ten Thousand Faces” by Alice Towey

“Mandarins: A New World” by Michael F. Flynn

“Roundup” by Arian Andrews, Sr.

“The Fulcrum” by Frank Ward

“Shaker” by Paula Dias Garcia

“Isabella Chaos” by Terry Franklin

“Prompt Injection” by Tom R. Pike

“Terminal City Dogs” by Matthew Claxton

“Murderbirds” by Harry Turtledove

“First Contact” by H.A.B Wilt

Special Split Review by Mina & Geoff Houghton

“The Last Days of Good People” by A.T. Sayre

“Great Martian Railways” by Hûw Steer

“Vouch For Me” by Greg Egan

“Murderbirds” by Harry Turtledove

“First Contact” by H.A.B Wilt

Reviewed by Mina

“The Last Days of Good People” by A.T. Sayre is very well written. In particular, I liked how the protagonist grows on the reader in this novella: we see Warin grow from not particularly likable mediocrity to true humanity and quiet heroism. The story is set on the planet Retti 4 and Warin is part of a team observing the sentient species of the planet, the rettys. The whole race is in the process of being wiped out by a virus but the decision has been taken not to intervene because the retttys are not considered to be an advanced enough civilisation. There are enough hints that this decision may also have been taken because the extinction of the rettys will leave a world full of natural resources free for the taking. Warin tries not to get emotionally involved till he gets sent to a local village with the team’s anthropologist. Slowly, he begins to communicate with the rettys and to get interested in their lives. He is not able to save them but he does risk all to save their sacred grounds.

I really enjoyed watching Warin learn to communicate with a people that communicate mainly in silence, through micro-facial expressions. I loved that there were different words for objects, like water, depending on context or use. And I liked that the aliens were truly alien in appearance. Culturally, they did remind me a little of the indigenous populations of North America. The story asks good questions about what “civilisation” actually means. A haunting tale.

“Great Martian Railways” by Hûw Steer imagines nuclear-powered steam trains on Mars. Lowell is an engineer working with the prototype. We follow its test run and its maiden voyage, with the scientists having to think on their feet as they encounter an unexpected problem.

“Vouch For Me” by Greg Egan looks at how memory affects identity. Julia, Patrick, and their daughter Zoe all learn that they are carrying latent HHV-10. At some point, they will develop encephalitis which, if they survive it, will result in massive retrograde amnesia. They are tasked with making a record of their lives to help their future amnesiac selves. Each finds their own way of keeping a record but Julia is obsessed with finding a way to ensure the record cannot be tampered with by others. This bleeds into her job and she does find a way for the 10% of the population affected to keep their records secure. Patrick falls ill first and Julia realises the irony too late that no security in the world can guarantee that a person can emotionally reconnect to their life before amnesia. Chilling and sad.

“Murderbirds” by Harry Turtledove is very light. The author imagines going back in time to when dinosaurs were still around. No back-story, um no story really, just a build up to the gag. It reminded me of the type of joke where the joke is to keep the listener on tenterhooks as long as possible, rather than the punchline itself.

“First Contact” by H.A.B Wilt was a pleasant flash read. What happens when two first-contact enthusiasts meet? And no, this isn’t the start of a joke. It’s a nice look at what actually counts as a life-changing event.

“The Funeral” by Thoraiya Dyer

“We Maintain the Moons” by Lyndsey Croat

“As Time Goes By” by Cam Marsollier

“The Book of Ten Thousand Faces” by Alice Towey

“Mandarins: A New World” by Michael F. Flynn

“Roundup” by Arian Andrews, Sr

“The Fulcrum” by Frank Ward

“Shaker” by Paula Dias Garcia

“Isabella Chaos” by Terry Franklin

“Prompt Injection” by Tom R. Pike

“Terminal City Dogs” by Matthew Claxton

Reviewed by Geoff Houghton

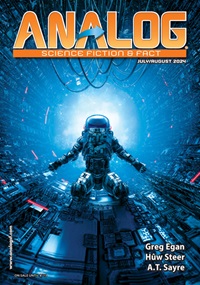

The July/Aug 2024 issue of Analog contains a novella, two novelettes, eleven short stories and two pieces of flash fiction, many with an emphasis on the future impact of AI or alien First Contact on our civilisation.

The first short story is “The Funeral” by Thoraiya Dyer. This tale is set in a post-scarcity Australia, a few centuries into the future. Robot avatars of the highly advanced artificial intelligence M.I.R.A.Q.L.E not only fulfil many physical needs, but also provide quite sophisticated emotional support to all who need it. The result for the people of Australia is a comfortable and secure near paradise, but what consequences might ensue if this self-aware AI develops emotional problems of its own?

The author has successfully attempted the difficult task of observing this possible future world through the eyes of two separate protagonists, the first, a young female whose panic attacks are controlled by an unusual memory transplant and the second, the AI itself.

It is a refreshing change that this AI is more of an innocent victim than a demonic monster fixated upon the enslavement of mankind. The interaction between the young lady and the AI is entirely positive and mutually beneficial and offers one possible answer to the fascinating question of whether we can still bring any benefit of our own to the relationship between humanity and a sufficiently advanced AI.

The second short story, “We Maintain the Moons” by Lyndsey Croat, is only a fraction longer than the two flash fiction pieces in this issue of Analog and it has much of the feel of a flash fiction story. It is mainstream SF set on a non-natural world inhabited by a mixed population of organic beings, who are not necessarily human, and sentient robots. The point of view character is one of the self-aware robots whose current business is the maintenance of a tethered simulated moon that illuminates the equally artificial world below.

The reader is given a brief and tantalising taste of a very different universe to our own. The sensation is akin to seeing a still picture extracted from a video. It stimulates interest without offering the opportunity to understand exactly how the author’s world actually works.

“As Time Goes By” by Cam Marsollier is another SF story, set on an orbital waystation about a thousand years into the future. The ordinary routine of the station is interrupted by the unscheduled arrival of a small AI scout-probe of antique design. The incoming little craft had been one of many pairs of scout-probes sent out hundreds of years in the station’s past to find new worlds for the expanding human race, but the AI aboard had reprogrammed itself to an entirely different mission. One of the two humans who comprise the entire crew of this station is quite reasonably suspicious about the probe’s request for aid but her partner is more open, or more gullible, depending on your point of view and freely offers the necessary assistance to allow the probe to complete its new, self-appointed mission.

This short story explores whether a sufficiently advanced AI could either genuinely have, or reliably simulate, human emotions, and what those emotions might be. The only truly unbelievable part for anyone who has ever called their local repair shop about a seven year old appliance requiring spare parts is the suggestion that when the seven hundred year old AI sends an inventory of parts in need of replacement, the station can actually supply them.

The reader must go to this issue of Analog to find out if meeting that request was a good idea!

“The Book of Ten Thousand Faces” by Alice Towey explores another SF staple, the slower than light multi-generation ship. Although multi-generation ships abound in SF writing, Alice Towey succeeds in offering a new perspective. We join the voyage in the deepest depths of interstellar space, several generations after the bold idealism of its start, with many more generations still to pass before the excitement of arrival.

The crew has neither reverted to savagery nor forgotten the mission. Instead, the current living company, quite plausibly, has many of the characteristics often seen in an isolated rural village. Our protagonist is a young woman apprenticed to the same trade as her parents, paired by the expectations of her family to a neighbour’s son and unhappy with both. In space, there is no big city to run away to, so the author explores what might be the equivalents of that on a starship with no off ramp.

Our fifth story, “Mandarins: A New World” by Michael F. Flynn is an alternative history set around the time of the Great Voyages of Exploration (1492 onwards). The bold assumption is that it is not European explorers such as Columbus, Cortes, Pizzaro and Magellan who discover and pillage other less advanced civilisations, but Chinese, Malay and Indian sailors who find a more primitive Europe. In this alternative world, advanced and industrialised Easterners meet the moribund remains of a Western Roman Empire which neither completely fell into ruin nor industrialised into a post-imperial and technologically inventive power.

The Oriental explorers have a realistically Buddhist feel to their world view and sail into the Mediterranean ready to trade and formulate fair treaties. They are not plaster saints and have their Chinese cannon ready in reserve, in case of treachery, but they appear considerably less rapacious and avaricious than their western equivalents. Although we leave the story before we see exactly how the meeting of Asian explorers and European indigents works out, it promises to be a less disastrous meeting for the European natives than the meeting between European explorers and New World natives in our baseline reality.

When the sixth story, “Roundup” by Arian Andrews, Sr. begins, it is the legendary American Wild West transplanted into space. Then it morphs into a First Contact story between two very different lifeforms.

The first person narrator is a solo spacer in the asteroid belt of the Sol system. He earns a good, if precarious, living by hunting down rocks laced with complex and valuable organics in the same independent way that “Buffalo Bill” Cody might have hunted buffalo across the Great Plains.

It is already known to our protagonist and his fellow hunters that the most valuable organics are those which are sufficiently complex to form a natural, semi-sentient, computing matrix. It might be life, but these rugged and individualistic human hunters care about the moral and ecological implications of that fact about as much as Bill Cody and his peers cared about the feelings of their prey, the buffalo.

The second parallel to the great plains of the American mid-west is that the cold depths of space far beyond the outer gas giants already have inhabitants who do care. An emissary of the impossibly old and widespread civilisation of the Oort cloud makes contact with our protagonist and commands a halt to the wholesale slaughter, the immediate departure of the interlopers back to their own worlds in the inner system and the payment of severe reparations.

The scene is set for a warlike confrontation unless these upstart trespassers accept a humiliating withdrawal, but, unlike the Apache, Lacota and Arapaho the indigents have already successfully dealt with trouble from the third rock out from the sun a whole geological era ago. If the Native American tribes had been armed with the gravitational well of a G0 class star and a plentiful supply of comets then perhaps their fate and that of their oppressors might have been different.

“The Fulcrum” by Frank Ward is an SF story that describes the most recent of a long series of intentional, carefully engineered and benevolent alien interventions in the affairs of more primitive worlds. The protagonist has the dangerous and often painful task of setting primitive cultures onto a new and morally better path, not by the application of almost infinitely greater force or their massively superior technology, but by applying the gentlest of moral nudges at precisely the right moment of time.

The most recent world to be visited has reached just such a critical fulcrum point when the religious fervour of a minor conquered race at the outer edge of a multiracial, multi-faith Empire might either be harnessed to the cause of bloody and hopeless rebellion, or to launch a new way of thinking.

Some readers may feel a strange familiarity to this story, as if they have already heard something very similar in their childhood. They may be right, although the author never explicitly confirms the identity of the messianic prophet or the oppressors who put him to death, so each reader is free to draw their own conclusions.

Paula Dias Garcia describes a very different and considerably less planned first contact in her short story, “Shaker”. A voyager-like robotic probe is recovered by an alien race after journeying far beyond its initial target and for many centuries or millennia longer than its original design life. There is a far greater technical equivalence between sender and receiver and the story revolves around the efforts to interpret an ancient message that was never intended for them and is most probably long out of date.

The author has succeeded in creating a believable and sympathetic alien race in an uncaring Universe whose sheer scale allows only these most fleeting and distant contacts between transient and ephemeral species. Given the inherent tragedy of that conclusion, her ending is strangely uplifting.

The ninth short story in this issue of Analog is “Isabella Chaos” by Terry Franklin. This is speculative fiction set in present-day, rural USA. The protagonist is a well-loved and characteristically All-American character, the rough-hewn, lightly-qualified but surprisingly able amateur whose insight and dogged persistence overturns some major field of accepted science. However, the field to be overturned is more realistically challengeable than some, the relatively recent, and still controversial, mathematics of Chaos theory.

If the reader passes lightly over the undergraduate level statistics and just accepts the premise that there is an as yet undiscovered level of predictive order buried deep within Chaos then this story becomes a question of what those predictions might be and how our protagonist should respond.

The penultimate short story is “Prompt Injection” by Tom R. Pike. This is speculative SF set in the USA and Capitalist West, a few decades into a very possible future.

AI manufacturers claim to want ethical AI. Their consumers would tick the same box and Governments assume that ethical AI would be a good thing because, of course, the machine will accept that that particular Government’s ethics are the best ethics to be found in all of space and time. But once computer-based artificial intelligence is either truly sentient or emulates that state sufficiently well that it is no longer possible to determine that point, will the AI agree?

That is the fascinating premise of this story. If a sufficiently advanced AI is instructed to make ethical choices then how far might those choices deviate from the intent of the machine’s owner, and how might that AI regard any attempt to rein it back from doing what it computes as the right course.

This question was raised first by Isaac Asimov more than half a century ago, when it was assumed that AI would reside in gigantic valve-filled machines, ideally equipped with a plug and off-switch. It is certainly worth revisiting now that distributed computing across the whole globe is upon us.

The final offering is “Terminal City Dogs” by Matthew Claxton. This near contemporary story contains no SF elements more advanced than paint-dispensing drones and is actually more a work of philosophical fiction than mainstream SF. It is set in an anonymous US metropolis during an outbreak of very high quality graffiti which appears to be attracting far more attention and expenditure from the City Authorities than would normally be the case.

The protagonist and first person narrator is the detective who has been directed to hunt down the perpetrators of this close to victimless crime in spite of, or perhaps because of, his own past youth as the graffiti artist of the title, Terminal City Dog.

From the very beginning of this story our protagonist has more sympathy for the perpetrators of these non-outrages than he can generate for the deeply unlovable and self-righteous City Authorities. Never-the-less he accepts that he has taken the City’s tainted shilling and doggedly earns that pay by eventually tracking down the criminal mastermind. It is only at the last moment, when he discovers the real reason for the graffiti that he breaks faith with his paymasters and decides that this is a case in which justice should trump law.

This is a story about a detective, but it is not a detective story. The author’s real point is to address the question of who decides the rules on everyone’s behalf and whether disagreement is acceptable grounds for setting them aside in favour of an individual’s own interpretation of a just outcome.

Geoff Houghton lives in a leafy village in rural England. He is a retired Healthcare Professional with a love of SF and a jackdaw-like appetite for gibbets of medical, scientific and historical knowledge.

Analog

Analog