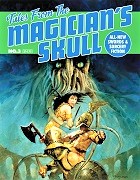

Tales from the Magician’s Skull #3, October 2019

Tales from the Magician’s Skull #3, October 2019

“The Face that Fits His Mask” by William King

Reviewed by Tara Grímravn

Sword-wielding heroes, exciting adventures, and supernatural thrills—these are the hallmarks of the sword and sorcery genre. For readers who thrive on these elements, most of the seven tales presented in this bi-annual issue of Tales from the Magician’s Skull will not fail to deliver.

“The Face that Fits His Mask” by William King

Someone in the city of Alstadt has been kidnapping children and sending them back to their parents in small pieces. Kormak, a Guardian of the Order of the Dawn, has been selected to ferret out the culprit behind the murders. He begins by questioning his old nemesis Skardus, a retired Ratkin assassin posing as a human merchant. Skardus suspects his brother-in-law, Anton, of being behind the kidnappings and agrees to lead Kormak into the Undercity to find him. But the Undercity is a dangerous place even in times of peace, and the intrusion of a human like Kormak could spell war and disaster for Skardus and the rest of the Children of the Moon.

On the whole, this is an excellent story by King—at least as far as the plot is concerned. Unfortunately, it’s a bit hard to tell which character is leading the narrative: Kormak or Skardus. At the onset, it would appear this was Skardus’s story, especially considering that he’s the first of the pair that we meet, but then the point of view quickly switches to Kormak. From that point on, it continues to flip back and forth between the two men without any indication that this is going to happen. And, although we spend far more time in Kormak’s head, at the end of the day, it’s not entirely certain who the main character is really. Then, near the end of the story, the point of view switches to Anton. Overall, it’s very disconcerting.

It also would have been nice to know that Skardus was a Ratkin earlier on. At first introduction, it’s clear that he’s not human, which is okay, but the constant threat that he might change leads one to imagine werewolf. While it might ultimately make little difference to the plot itself, in terms of characterization, it’s quite an important tidbit of information. The same goes for Kormak. When he’s first introduced, Skardus describes his energy as dark and demonic, leading the reader to believe that he’s not human, either. Later, however, it’s revealed that he’s just a normal human trained to be a monster-hunter.

“By That Much” by Joseph A. McCullough

Nick Bury digs graves. He never seems to be directed to dig them by anyone or for anyone in particular. It’s as if he just knows that the intended occupant will soon arrive. As he sits down in a field beside his handiwork, a body drops from the sky, missing the open pit by mere inches. Later, near the bank of a river, he meets a deposed young king running for his life who collapses at the edge of the freshly dug grave. Then, Nick waits beside an open plot in a graveyard, when he’s approached by six men carrying a coffin. And finally, he witnesses a duel to the death after just having excavated two new burial plots.

I really can’t say much about McCullough’s work without giving away spoilers. The summary I’ve given is more than spoiler enough, even if nothing goes the way one might expect. “By That Much” is incredibly short at only 219 words, and the notice at the end that the story is “continued on page 24” is somewhat misleading considering that it’s actually one of a set of four separate yet connected tales about Nick Bury, a mystical gravedigger and possible a stand-in for Death itself. All are presented in this issue but each has a different title, which caught me off-guard at first.

The four pieces of McCullough’s short saga are entertaining, to be sure—after all, I have to admit to wearing a wry smile as I read each minuscule morsel of black humor. The next installment, titled “Dead Wood,” does indeed follow on page 24, with the conclusion of the king’s ordeal not turning out the way one is led to believe it might. The same goes for “The Return” and “Duel’s End,” each scenario resolving in one unexpected fashion or another, with a single exception—someone always ends up in the pit.

The only note that I have on McCullough’s stories is for the editor. Because each piece has its own title and the only clue that they’re related is the main character’s name, I nearly passed over the final three pieces as I looked for the continuing narrative, thinking that they weren’t connected to the original title “By That Much.” I simply assumed McCullough had written a few additional small editorials or other articles for the issue, and that the “continued on page 24” notice was a mistake. It was only after I caught the name Nick Bury in the text while scanning the page that I realized otherwise.

All in all, though, I thoroughly enjoyed Nick’s odd little adventures, regardless of whether he’s some supernatural embodiment of Death or just an incredibly intuitive gravedigger.

“Tyrant’s Bane” by John C. Hocking

With his master, Thratos, dead, Benhus has inherited his estate and title as the King’s Hand. He’s also been given a new task by King Flavius himself—investigate the death of royal favorite Viriban and the disappearance of his body from the City Mortuary. As instructed, Benhus travels to the mortuary to meet Sandril, a Southron shaman. Once inside the house of death, the pair discover a conspiracy aimed at torturing and killing the King, a plot in which the missing body of Viriban is somehow involved.

Ah, necromancers. Who doesn’t love a good story about raising the dead to carry out nefarious deeds in the name of some dark sorcerer? I certainly do and this is a fun story to read. With its hints of Roman, Greek, and perhaps Mesopotamian elements, I quite like the interesting mix of influences that Hocking has cobbled together to make his world, as well.

My only issue with the story lies with Benhus. As a character, he’s exactly what one would expect in a sword and sorcery tale. He follows the typical Hero archetype, going from an unsure boy to feeling far more comfortable with his role as one of the King’s protectors by the end. Unfortunately, his characterization breaks down in a brief passage of just a few sentences that I’m assuming is meant to help flesh out his character for the reader. The passage reveals that Benhus killed his master Thratos and emphasizes that he wants to be known as the King’s Blade, not the King’s Hand. First of all, this is a rather huge bombshell about Benhus’s character that’s not at all relevant to the story being told. Knowing that Thratos was dead and his position was given to Benhus is enough for this particular narrative, details which are all revealed in the first few paragraphs of the tale.

Unless the manner of Thratos’s death, in this case at the hand of his squire, pertains to the story, it’s not needed. There’s no need to drop such a huge confession on the reader if it has no bearing on the story. Well, at least not this far in, at any rate. It would have been a bit more acceptable earlier on when Thratos’s death was first mentioned as long as some type of reasoning had been presented, as it would have helped to establish Benhus’s character. Five pages into the tale, however, is far too late in the game for this. The audience is supposed to see Benhus as a budding hero but, dropped into the middle of the story without explanation as to why, that detail only makes him look like a social-ladder-climbing murderer, far worse than those we are supposed to see as enemies—namely, the necromancers who are trying to kill Flavius. They do so as an act of revenge for atrocities committed by the King, further evidenced by his treatment of Sandril at the end. The necromancers’ actions I can reconcile as a forgivable and reasonable sin; not so with Benhus. By only telling us he murdered his master without giving us the why behind it, Benhus becomes a hypocrite, not a hero.

In addition, Benhus’s preoccupation with being called the King’s Blade instead of the King’s Hand is not explained. Why does he want that title to change so dearly? Is it guilt over his role in Thratos’s death or is it him trying to distance himself from a tyrannical master? Or is he trying to establish his reputation on his own merit? I could go on but my argument all boils down to the fact that, if one is going to bring little details like these into the story, they need to be relevant to the plot and further the story. Otherwise, they need to further character development but, for that to work, something of such enormity can’t be treated as unimportant, ambiguous backstory.

“Five Deaths” by James Enge

Lernaion and Morlock, both members of the Graith of Guardians, are on the trail of a harthrang—a demon who has taken possession of a human body. The trail leads them to the long-abandoned subterranean dwarven city of Kwelmhaiar. As they venture deeper and deeper into the labyrinthine halls, the traps laid by the demon become ever more dangerous as they close in on their foe.

Right off the bat, Enge’s story has echoes of Tolkien. The description of the abandoned halls beneath the mountain is very reminiscent of the Fellowship of the Ring’s descent into Moria. I’m a little confused about how the harthrang had taken control of the sorcerer’s body, though. If Lernaion and Morlock had found both the sorcerer’s body and the demonic contract half-burned before the story begins, then how or when had the demon taken the body? From what is written, it doesn’t appear that the demon was present at that pre-story moment but he obviously has taken full possession of the corpse by the start of the story. And, considering that they had read the contract (Lernaion certainly knew what it was) and knew the demon would do this, why didn’t they destroy the summoner’s body then? Why wait till the demon had taken possession of it? The author may have had some reasoning behind this, but it’s not presented in the narrative.

Lernaion is also a perplexing character. Every other sentence, he’s either rebuking Morlock for some imagined minor infraction or looking on him kindly. It makes it hard to get a bead on him as a person. Then, when Morlock is washed away in a flood, he suddenly sprouts gills. Based on what’s written in the narrative at this point, this is a normal physical trait for Lernaion’s people but it was a surprising revelation at the moment, to say the least.

Regardless of any of the above, however, I quite enjoyed Enge’s story and recommend it to readers.

“The Forger’s Art” by Violette Malan

Mercenary Brother Renth Greyclaw is dead. He’d been asked to steal a statue of the God of Lost Things, Tuluaran, from the god’s temple, only to be rewarded with a death curse when it became evident that the item he’d retrieved was a copy often displayed by the priests in place of the real one. Swearing vengeance,

his fellow Mercenaries Parno and Dhulyn are hot on the trail of the mage who killed him.

Malan’s story is nothing worth noting, rife with bad writing and a lack of imagination. The dialogue, for a start, is forced and cheesy. Nothing about it seems natural and it’s so clichéd, it’s cringe-inducing. Then, of course, every enemy they encounter is useless and designed to be so inferior to Parno and Dhulyn that it’s maddening. For example, the main villain, a supposedly powerful mage, poses no threat whatsoever to them. And the mage’s guard is so distracted by his own disbelief in the heroes’ reputation that he chooses to wax on about it when he meets Parno and Dhulyn instead of being on his guard like anyone else would when confronting a potentially deadly opponent, even if they didn’t believe the rumors of their strength and skill.

The worst part of all this is that the “heroes” are nigh indestructible, a fact with which readers are beaten over the head constantly and forced to wade through glowing praise for the supposed prowess of the pair and their organization in nearly every paragraph. All of this inevitably calls into question the believability of how the mage was able to take down Renth to begin with. In the end, there is nothing at all believable about any of them, including the method by which the so-called heroes determine where the mage may be hiding. It is, in fact, the poorest example of tavern storytelling I’ve ever read in a tale and I find it highly unlikely that it would have elicited the information they were seeking as it did.

To top it off, there’s the poorly executed use of deus ex machina in the form of Tuluaran, a device best avoided in most instances. It’s just clumsy writing. I could go on but it’s far simpler to say that this entire story is a hot mess and a complete miss.

“The Second Death of Hanuvar” by Howard Andrew Jones

Just a few months ago, the city of Volanus was destroyed by the Dervani. Jerissa, a member of an elite fighting force called the Eltyr, and a few of her fellow soldiers were among those captured in the city’s fall and sent as slaves to train in a Dervani gladiatorial school. But as the city of Hidestrus prepares for a festival to celebrate the victory over Volanus featuring a gladiatorial reenactment of the battle, Hanuvar, thought killed in Volanus, returns to free his Eltyr. But as they make their plans, a threat grows in the shadows. Some will stop at nothing to bring a dark goddess back to the world, and they require the deaths of the Eltyr to do just that.

There’s very little to say about Jones’s story aside from the fact that it is honestly quite excellent. The Greco-Roman setting was a nice change from the usual medieval Western European environment one often finds in these stories. Jones quite clearly put a lot of research into his work before writing it. The description of the amphitheater and its underground labyrinth and workings were on point, as were his battle scenarios and gladiatorial school.

“The Wizard of Remembrance” by Sarah Newton

In a time before history, Suven the Sorcerous, a bloodthirsty warlord, had murdered uncountable innocents in the name of the Empire of Ubliax. Whenever the pain and regret for his actions became too much to bear, so much so that even his wives couldn’t ease his suffering, he would call the memnovores, demons who devoured memories, and his mind would be wiped clean of his many atrocities. There comes a day, however, when Suven can no longer stand to live with the horrors he’s committed and decides to become one of the Emptied, mindless soldiers of Ubliax and their demons. He ventures to Ubal-Gathor, the Empire’s capital city, to take the ritual. But the change that Suven undergoes is not the one he expects, leading him to fight for freedom from Ubliax.

Another work set in a non-Western European setting, there are traces of Sumerian and Egyptian myth threaded throughout Newton’s story. One can see the distinctive mark of Lovecraft in the memory eaters. The writing style is quite dramatic without venturing into oft-dreaded “purple prose” territory. Even so, some readers might find it a bit heavy and cumbersome to get through, especially if they’re expecting the typical style common to sword and sorcery. Personally, I quite liked it, having often used it myself when the story I’m telling is meant to live in myth, which is, I believe, Newton’s aim in this piece. It’s not so much an adventure written with a sense of immediacy like the others in this issue, so much as it is a recounting of a heroic event long before humans thought to write them down, if that makes sense. It’s a legend with all the feel of an ancient oral tradition of how the Cult of Forgetting was overthrown by the Cult of Remembrance. All in all, it was a great read.