"Ain’t nobody works with honey bees who doesn’t get stung at least once." This is not a saying I’ve heard before, but it does sound like a good one to keep in mind, just in case. In

story, this line is the capstone of "The Last Bee Tree in Lynchburg County," the tale that Abigail’s family has passed down from one generation to the next: the tale of how the bees came to stay in the old cottonwood tree on their family farm. The bees are biomechanical—part biological and part robot—and like many other robots in science fiction, they turn out to have a mind of their own, more than their creators had intended. This anecdote is related as a joke, but what Morrison has created here is an idyll, where a family’s heritage is handed down from one generation to the next, where there will always be fresh lemonade waiting on the farmhouse porch, where the bees still make honey but never sting.

"The Little Tailor" is another story we have all heard. In this version by

Stephanie Burgis, the old tale becomes a model for a man’s life, for his rise from poverty and obscurity to success and prosperity. The fantastic elements are only a thin disguise here; we know that the hero is really Grandfather, that the princess is actually a businessman’s daughter. Like the tailor, Peter Bulgarin [which is not his original name] allowed people to believe he was what he was not. He passed as a hero, as an aristocratic exile. As is fitting for a hero, he won the princess as his bride, and they lived happily ever after—almost. For all the rest of her life, Grandma could never get over the fact that he had lied to her, that his life had been based on lies. Yet we suspect that Grandma might be wrong. For if he had remained in Russia, a poor but honest tailor, Grandma would never have met her prince.

Larry Hammer‘s "Paul Bunyan and the Photocopier" tells the story of what happened when the legendary giant lumberjack, now owner of a publicly traded lumber business, makes copies while his secretary is on vacation. When the copier jams, Paul decides to make his own. In order to make a plane of glass for the paper to sit on, Paul decides a frozen lake will do, and makes a lasso out of paper clips in order to drag the edge of a lake to his office in Chicago. This is how Chicago became a port city. Paul decides that volcanic ash will make a good substitute for toner, and drags a volcano near, then lassos the sun to use as the bright light that all photocopiers use. This is a clever, funny tall tale for modern times, and was great fun to read. It gives a nice nod to the old tall tales, while adding a new one to the genre.

In "Vision" by Hannah Wolf Bowen, Bastian is an artist. Word at the university he left years ago is that he could have been a someone if he’d stuck with it. His old teacher sends a young student to him seeking his own answers. But Bastian doesn’t have answers, not anymore, wondering now if he ever did. Some days he knows what makes him happy—his art, pigeons in the park—but mostly he’s searching himself, stumbling with his gift. Bastian, if he chooses, paints "might-have-been"s with his eyes closed, images that always come true. And what his compositions tell him is that he will be forsaken by love, left heartbroken and alone. Should he risk his heart again in a love that he knows is doomed, or love as he can, when he can? Does being able to predict the future enslave one to it? "Vision" is a rambling, sleepy story, filled with rich imagery and lush descriptions.

Last up, in "White Shadows,"

Sonya Taaffe gives us a day in the life of Fetch, a sort of shape-shifting doppelganger who steps in and out of others’ identities, leaving them discarded behind her as she moves on to another. She seems to pick up an identity from the mind of someone who knows that person; for a few moments, she is someone else, she is alive. But the brief encounter always has consequences—not for Fetch herself, but for the person she has doubled. Lives are altered, but Fetch goes on, to the next identity, and to the next.

In this piece, there are no old fairy tales that we have heard before, no stories repeated. There is only Fetch, who follows this pattern from one day to the next; her story varies, but it is always the same. Taaffe’s title, "White Shadows," describes Fetch’s shadow; in her, the colors are turned inside-out. But this reviewer, at least, has heard that one before. Do you remember Coach Reeves? Do you remember Corky? I suspect that these are associations which Taaffe did not intend.

Altogether,

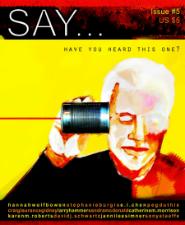

Say . . . have you heard this one? is a collection of fiction which rewards the curiosity that the title is intended to evoke in the reader. I look forward to seeing what the editors will come up with next. But I do hope that by the time the sixth

Say . . . appears in print, they will have engaged the services of a good copyeditor.

(Reviewed by Lois Tilton except for "Practical Villainy" by Jannie Lee Simner and "Paul Bunyan and the Photocopier" by Larry Hammer which were reviewed by James Palmer and "Vision" by Hannah Wolf Bowen which was reviewed by Eugie Foster.)