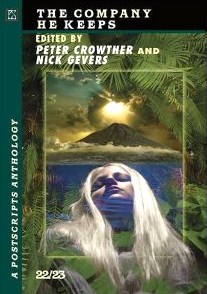

Postscripts 22/23: The Company He Keeps

Postscripts 22/23: The Company He Keeps

Edited by Peter Crowther and Nick Gevers

(PS Publishing, September 2010)

“The Company He Keeps” by Lucius Shepard

“The Hollow Framework For The Cotton Man” by Catherine J. Gardner

“The Fishes Speak” by Michaela Roessner

“Only One Ghost” by John Grant

“The Human Element” by Eric Brown

“Adam in Amber” by Gary Fry

“Bully” by Jack Ketchum

“Ne Cadant In Obscurum” by David Hoing

“Moving Day” by Robert Edric

“Never Always Comes” by Joel Lane

“The Man Who Scared Lovecraft” by Don Webb

“The Men at the Mound” by Jonathan Thomas

“Harvesting The Moon” by Ursula Pflug

“One Hundred Sentences About The City Of The Future: A Jeremiad” by Alex Irvine

“Marco The Magnificent” by P. D. Cacek

“Dreamspace” by Quentin S. Crisp

“Alice Bleeding” by Rio Youers

“Sinners, Saints, Dragons, And Haints,

“In The City Beneath Still Waters” by N. K. Jemisin

“Osmotic Pressure” by Jack Deighton

“Signs Along The Road” by Richard Parks

“The Desiccated Man” by Chris Beckett

“The Figure In Motion” by Steve Rasnic Tem

“Are You Sannata3159?” by Vandana Singh

“The Time Traveller’s Breakdown” by Gregory Norminton

“Pillar Of Salt” by Robert Swartwood

“The Forever Forest” by Rhys Hughes

“The Farmer’s Wife” by James Cooper

“Pages From An Invisible Book” by Darrell Schweitzer

“Of Hearts And Monkeys” by Nick Wood

“Drive-In” by Peter Hardy

“The Rescue” by Holly Phillips

(This is a split review. The first 15 stories are reviewed by Maria Lin, while the remaining 17 stories are reviewed by Robert Leishman.)

Reviewed by Maria Lin

Postscripts 22/23 is a motley selection of stories hitting a broad range of genres. The first half of the collection was consistently decent, with a few standouts. Nothing blew my mind, but as a whole the collection was entertaining.

“The Company He Keeps” by Lucius Shepard

The sins of the Hollywood elite and those who accompany them are put on full display in “The Company He Keeps,” by Lucius Shepard. Danny Centers, flunky of the actor Kevin Snow, is an aspiring writer who has known his boss since high school. He doesn’t enjoy the back pecking nature of his work and enjoys even less the two back peckers he works with, but he seems to have taken a stoic approach to his situation and deals with the demands of a spoiled boss and the harassment of his co-workers with a minimum of outward reaction.

It’s New Year’s, and Kevin has decided to camp on the side of a Mayan volcano with his entourage and his actress girlfriend Nedra Hawes. Centers is enjoying some peace and quiet as the night is winding down until Kevin approaches him with a confession. He’s just killed Nedra and he needs Centers’ help in covering up the crime. As disgusted as Centers is with Kevin and his behavior, he agrees to help and concocts a plan that will protect Kevin from scrutiny.

There’s something going on with the volcano, but whatever it is is very subtle and does not have any marked effect on the plot. Whatever hint of the supernatural there is is negligible, and so “The Company He Keeps” is a straightforward story of murder and the spiritual degeneration of a small group of men who care more about their careers than the fact that a young lady has just died violently. “The Company He Keeps” is rather good, with mind games, double takes, and a cynical but complicit point of view. It takes the Hollywood stereotype and expands it to dramatic effect. If you like stories where morally bankrupt people do horrible things and then get away with it, this one is for you.

“The Hollow Framework For The Cotton Man” by Catherine J. Gardner

Horror and humor mingle as two women are chased by a scarecrow into a tollbooth that will never let them go. Ronnie and Lulu are driving off to meet Ronnie’s boyfriend when they realize they are being hunted by a scarecrow. The scars on Ronnie’s legs suggests that this is not her first encounter with them, for whatever she did to escape the first has not taught her much, ends up letting it herd her towards a road where a man demands sixty-six Hungpop dollars, or else.

With the scarecrow waiting behind them, a man who is definitely not human making impossible demands, and a car that is “making all the right noises” but refuses to budge, Ronnie realizes that she has fallen into a trap from which she will not be escaping.

“The Hollow Framework for the Cotton Man” comes at a perfect time of year, and adds a little more creepiness to farm fields already made terrifying by prior horror stories. While having a scarecrow chase you is rather high on the scary factor, the toll man in the story is one of those insane and amicable sorts, and the manner of Ronnie’s fate, a questionnaire with infinite and macabre questions, is a much more lighthearted element than you find in a basic monster chase. I had myself a good snicker at Ronnie’s expense, but will be watching my back as I drive down farm country roads in the near future.

“The Fishes Speak” by Michaela Roessner

Michaela Roessner takes a risk with “The Fishes Speak” and tells her story in the difficult second person present. “You” are whoever you are, with not much specific beyond the fact that you have a lover, and were raised Catholic but lapsed quite a while ago. The fish in the world are starting to speak prophesy from every religion, and the world is mesmerized. At first nothing happens beyond the fact that fish start flying off the shelves of local grocery marts, and people start visiting aquariums at an unheard of rate, but mankind’s infatuation with the phenomenon continues to grow until cities are crumbling and people are drowning themselves wholesale in the oceans of the world.

“The Fishes Speak” is an apocalyptic story where the fish never reveal a motive for starting to talk, and the humans never figure out what’s going on before they’re all dead. I prefer my end times to be a bit more sensible than that, but the absurdity of the story is also its charm. It takes an unassuming, even boring animal, the goldfish in a fish bowl, and re-imagines it as something to be wary of. It presents the progression of the main character from wary and afraid to fully aware, by whatever it is the fish have done to him/her very smoothly, and from the second person point of view successfully. No small feat.

“Only One Ghost” by John Grant

“Only One Ghost” is a bibliophile’s horror story. That is to say that the victims are books. A man purchases some used books and discovers his faded signature between the covers. Soon he has realized that not only the books he has just bought, but every book he owns, is defaced in such a manner, and his wife’s collection is similarly marked with her name. John Grant plays on the obsession some book lovers have about the purity of the books in their possession.

The main character is prepared to chalk the signatures up to some sort of quantum confusion between alternate universes, but when he notices that a single book has neither his nor his wife’s name, but the signature of a stranger scribbled in, he becomes sleepless with the anticipation of what effect that person will have on their lives.

The story stops there, and the nature of one signature’s significance is left for the reader to decide. As a concept the story was very intriguing, but as a story it seemed to stop just as it was getting started.

“The Human Element” by Eric Brown

Who better to perform a murder than a murder mystery writer? This is the question asked in “The Human Element,” by Eric Brown. Two writers, one who rises to fame and accomplishment through his attention to craft and character, and another who devolves into hackdom with stories held up by the novelty of their plots and little else, become estranged and part ways until the latter of the two commits suicide and the former goes to attend his funeral. Derek, the successful one, reminisces on his friendship with the deceased and the creative disputes that ended it. Frankie Pearson, the hack, seemed to never get over the fact that Derek had cut ties with him, and Derek can’t help but wonder if his rough treatment of his friend, including harsh reviews of his work, didn’t somehow contribute to Frankie’s death.

For the most part Derek’s concern is somewhat abstract. He hasn’t seen Frankie in years, and hasn’t thought about him in nearly as long, so when he finds out that he has been willed a small cottage he decides to visit once and then sell it without much hesitation. When he arrives at the cottage, Frankie is waiting for him, and he has not lured Derek into his trap for reconciliation.

“The Human Element” is a more nuanced approach to a standard mystery plot. The story itself reflects Frankie’s inability to see beyond the ‘twist’, but the conclusion highlights Derek’s, and the author’s, ability to add humanity to an otherwise simplistic and uninspired plot. The adage “character, character, character” is put to use here very well.

“Adam in Amber” Gary Fry

“Adam in Amber,” by Gary Fry is more complex than many of the others in this collection, but whether or not this complexity leads to any real meaning I’m not sure. It’s about a woman named Alice who goes to work full time to support her family after her husband is laid off from his job. Although she seems competent at her work, it soon becomes clear that she is not happy with the unconventional structure of her family, and is growing paranoid, if not neurotic, about her son’s well-being and her husband’s ability as a stay at home dad.

In an effort to calm herself down Alice picks a random tourist attraction on her navigation system and visits. The place is a garden, and in that garden appears to be a life-like sculpture, a corpse she calls it, sitting in a glass case. The sculpture, and more particularly the bee she sees settled on its lips, becomes nearly an obsession until a sting suffered by her son causes her to break out into a full on panic.

The tension in this story is provided entirely by the point of view of Alice, who has managed to agitate herself into such a fuss that the benign reality of her situation takes on a malicious element. Her husband seems like a good man from what objective information can be pulled from the narrative, but to Alice he is incompetent and incapable of caring for their child the way she, the mother, could. The strange figure in the park might be just what she tried to explain it away as, some strange modern sculpture, but Alice sees something more malicious there.

Fry ramps up the paranoia through excellent use of an unreliable narrator. It makes a relatively simple story about a woman who is going through a bit of a relationship and identity crisis more sinister. And there is the question of what significance, if any, the sculpture in the park really has, why it changes, and what bees have to do with it. There seems to be some strong symbolism there, but I couldn’t make much of it. I suggest you read and try to find the answer for yourself.

“Bully” by Jack Ketchum

Here is a straightforward story about abuse and deferred revenge that is all the more upsetting because not only is it possible for most of the events in the story to happen, but because these sorts of things still happen daily to spouses and children.

Jack Ketchum tells us a story in which a lady is pursuing the truth behind a family tragedy. A relative is said to have fallen down a well and broken her neck decades ago, but the protagonist doesn’t quite believe this story, and searches out some distant kin to get the truth. She meets an older cousin, the dead woman’s son, who tells her about his time growing up, and the true circumstances behind his mother’s death.

“Bully” doesn’t have much to it to set it apart from other similar stories about abuse, but it’s well told, and worth a read.

“Ne Cadant In Obscurum” by David Hoing

Time travel can be confusing. When the travel is erratic and your memory does not remain intact between jumps, it becomes almost unmanageable. When the narrator appears to be mildly schizophrenic and wavers between first and third person, it’s almost time to give up. It took me until nearly the end of the story to get a feel for the basics of what was going on, and the understanding was not really worth the confusion.

The gist is this: a lady named Anna has the power to travel through time and intends to use this power to save others, or at the very least bring justice to those who have died. The problem is that she can’t seem to end up at the right time, and when she jumps she never remembers why she jumped, so that often she is reminded of her purpose when she realizes that she has failed yet again. She seems to concentrate on two major areas, the years around the end of the Civil War, and the 1960s. She seems to warp in but not in body, as she finds herself in relationships with men she knows and yet doesn’t, and finds herself in different clothes and so on. But it’s hard to tell whether or not she is flitting between points of time within one body, or if she ages independently of the timeline and simply has a terrible memory.

Hoing uses this story to suggest that even with the power of time travel the past is immutable, but his narrator is just too obscure and flighty (to underscore the chaos of her time traveling no doubt) to send the message effectively. “Ne Cadant In Obscurum” is a neat concept, but it was not an enjoyable read.

“Moving Day” by Robert Edric

Throughout the myriad dystopias of the SF genre authors have envisioned the loss of everything from the planet earth to our very humanity. Robert Edric focuses on a more mundane loss, but one that triggers a strong emotional response. Mr. Miller is a man who is old enough to remember a time when one could see clouds in the sky and mountains on the horizon, but that time is apparently long gone. The pollution has become such that the tops of buildings are uninhabitable, and one’s field of vision is restricted to the power plants pouring out smoke close by.

The idea of using a smaller loss to highlight the overall degeneration of life in this future was well done, and Edric’s internal narration is full of character and emotion, but the story lacks a plot of any real substance. So, if you like vignettes of the future, Edric paints an interesting scene. If you want a story, “Moving Day” stops a tad short of that.

“Never Always Comes” by Joel Lane

The narrative jumps in “Ne Cadant In Obscurum” return here, sans time traveling. The timeline of events in “Never Always Comes” is much more easy to discern, but again there is some ambiguity as to what is actually happening. The narrator flashes back and forth between her terrible childhood and her unhealthy relationship with a man named Steven, a troubled writer who ultimately takes his own life. It seems that somehow Steven has stolen the narrator’s memory of her past, and the story is the narrator’s eventual recollection of it through old photographs.

Again we have a story that is well written, but plotless. The narrator speaks about the abuse in her house, her feelings of loneliness, and her terrible relationships, but to what end? Despite some excellent one-liners (“I went through the motions, playing the

role of myself.”), “Never Always Comes” did not spark any emotional reaction from me or give me pause to think. There’s too much feeling and too little of anything else.

“The Man Who Scared Lovecraft” by Don Webb

After reading a number of stories that had some flair to them but didn’t seem to go anywhere, “The Man Who Scared Lovecraft” was an interesting change. The writing itself is a lot less ‘literary’, and the narrator can’t seem to decide what tense he is in, but there is a story here. A pulp enthusiast named John Reynman discovers that an old writer named Carter is still alive and languishing in an old folks home. This Carter was apparently a sub-par writer back in his day who had the distinction of scaring H. P. Lovecraft away from one of his projects. Now 107 years old, Carter spends his days in an old folks home down in Florida.

A fellow pulp enthusiast and friend of Reynman goes to visit this Carter, but suffers a fatal heart attack during the meeting. The tragedy prompts Reynman to visit Carter himself in an attempt of sate his curiosity about Carter and the story he wrote that scared Lovecraft away.

“The Man Who Scared Lovecraft” has an old time feel to it, not just in its subject matter but in its style. There isn’t much artistic flourish, but the story is set straight and will probably please any fan of old time pulp fiction. This is also one of the few stories in the collection that had me a little nervous in anticipation.

“The Men at the Mound” by Jonathan Thomas

Two men become ghosts in “The Men at the Mound.” An ancient English king and a modern professor arrive at the same place at different times and yet meet at a country hill in the middle of the night. Both men are disturbed by the appearance of the other, but only the professor has some inkling of what he has just seen. Whether the two men meet each other by way of magic or temporal anomaly, Thomas doesn’t say, but he does provide an interesting take on the idea of ghosts.

“Harvesting The Moon” by Ursula Pflug

A young woman reminisces about her mother, her brother, and her mirror friend, in “Harvesting the Moon.” The setup is very similar to “Never Always Comes” and “Ne Cadant In Obscurum,” where a first person narrator tells a lot about her life in erratic bits. In this story the protagonist has the skill to pick moon berries, which grow on the side of dangerous cliffs, can cure almost any ailment, and cause the picker to be stigmatized within the community. Because of their properties and the effort it takes to get them, selling moon berries is a very profitable venture, and the narrator plans to sell enough to save up tuition for teaching school so that she can support her mother. She’s so concerned about her profits that she refuses to feed her mirror friend, an otter like spirit that lives in a bucket outside the house. Eventually this neglect leads to tragedy, and the narrator runs off, never having earned the money she had been so miserly about in the first place.

The pros and cons of this story are the same as those in those mentioned above. While the writing is creative, the story is lacking. There is no sense of change, growth, revelation, or even conflict, really, just a slow crawl toward one event after another. Perhaps this was intended, with the story’s mention of fate and its solidification, but it did not make for very interesting reading. The narrator feels very passive as she recollects things, and it seems like there is no real point where a choice could have been made, even though options presented themselves.

Without any sense of a driving plot, “Harvesting the Moon” sounds lovely but failed to grab my attention.

“One Hundred Sentences About The City Of The Future: A Jeremiad” by Alex Irvine

Written as a letter of complaint to some futuristic bureaucracy, “One Hundred Sentences” is an amusing peephole into a possible future where rain is scheduled and households are required to provide streaming entertainment to others. A father is upset about his options in the coming election, and writes a letter requesting information on filing a Notice of Intent to not vote. What follows is a litany of complaints and suggestions carefully limited to one hundred sentences, as required by feedback regulation.

The family in the story are familiar enough to be our next door neighbors, but the content of their letter is alien and full of futuristic notions. Although the one hundred sentences are a little padded, with multiple references to the limit itself, Alex Irvine’s vision of a future is tongue in cheek and full of interesting what-ifs, of which some don’t seem that far off at all.

“Marco The Magnificent” by P. D. Cacek

In “Marco the Magnificent” a dying boy spies on his elderly neighbor and discovers a secret. Old Mr. Baki pretends to be stooped over and hard of hearing towards his family and help, but when he thinks no one is looking his does pullups off the roof of his house and bench presses his car. Bedridden, Bobby spends most of his time watching out his window and keeping notes on Mr. Baki’s behavior, until one evening it becomes apparent that Mr. Baki isn’t the only one being watched.

P. D. Cacek has written a short, sweet story about heroism and childhood. She hits the tone of childhood on the head, and reading this story brings me back to the time when fantasy felt more like a matter of fact. If you’re looking for a story that will take some weight off your heart and a few years off your back, this one will do it for you.

The remainder of the stories are reviewed by Robert Leishman

In an open meadow people line up to enter Dreamspace, the creation of Morgan Dinos, a man who resembles a shaman for the purpose of fulfilling his celebrity. Lester is there with his daughter Clara to enter Dreamspace and experience what no one is able to describe. For them it’s a day out. For everyone, it’s an event.

In “Dreamspace” Quentin S. Crisp describes a day that’s supposed to be exciting, but harmless like most popular events. Instead it turns into something devastating. I liked the story because it got into describing how people react at public events when things go not as planned. And then of course there is the aftermath and the shared experience whatever it may be.

The ‘Alice’ in “Alice Bleeding” refers to a town named ‘Alice Springs’ which is very close to the center of Australia. Rio Youers has reintroduced a theme familiar to Australia – isolation. The outback was colonized by people who were often located several days away from their nearest neighbours. Aviation and modern telecommunication has changed that, but in this story Alice returns to a time before technology made a difference, when an Asteroid strikes central Australia.

Most of the buildings in Alice are destroyed and communications are knocked out. The survivors must decide what to do – to wait for rescue or to go and seek it. The story features Sally Ellis, a young mother who must decide what to do for the sake of her child and Luke, her baby’s father, with whom she has an on again off again relationship. But the real problem is that ‘they are coming’. Once the dust begins to settle, a portion of the aboriginal population takes the devastation as a sign to reclaim their land. A good story.

There have always been stories about New Orleans and of course stories about Katrina, but in “Sinners, Saints, Dragons, And Haints, In The City Beneath Still Waters” N. K. Jemisin is telling a story that isn’t what we’d expect to see on CNN. In this story Tookie, a middle aged black man, has lived in New Orleans his entire life. When the water begins to rise almost everyone either heads straight out of town or downtown to the stadium, but he scavenges a supply of food and stays in the family home with a shotgun handy.

The new city, the flooded city, begins to communicate with him. It has new citizens. Miss Mary, a neighbour whom he rescues from rising waters, tells him of what happens after hurricanes visit parts of the south. The word ‘Haint’ is used mainly in the Southern United States and usually refers to a lost soul or an evil spirit. It’s a good story about a man and his town.

“Osmotic Pressure” by Jack Deighton gives us a future where technology has given people more options when it comes to childbearing. An artificial womb, named a ‘woom,’ carries the child to term which frees the mother to do other activities. However, the woom still needs to be fed and an expectant parent is still an expectant parent.

Deighton gets us more and more into the psychological progression of the couple through the pregnancy and how the new technology affects that. It’s a good story in terms of character development.

Hobos, transients and wanderers have been in the rural culture for decades in the United States. Their stories often contain episodes of one traveller meeting another and sharing either their fortunes or misfortunes. In “Signs Along The Road” Richard Parks tells the story of Jason, an old hobo who’s been doing the same circuit across the southern U.S. for years.

As the story opens he’s recently met a boy on the road who identifies himself only as ‘Ken.’ Jason shares some stories with him along with some handy information about hobo lore. He also gives his opinion on a nearby crop circle.

Both have their secrets and both are wanderers. Parks does very well with this material.

I don’t know how many stories have been written about long journeys through space, but this one doesn’t really take place in transit, at least not that much. As the story opens the Rio Quinto IX is docking at a space station called New Vegas. There’s only one crewman on board, Captain Stone, and the station itself is deserted. But, upon his arrival systems activate themselves, the lights go on and the curtain rises in a facility designed to both entertain and distract Captain Stone. Thus starts “The Desiccated Man” by Chris Beckett.

The story takes an unexpected turn with the arrival of another starship captain, their encounter, subsequent activity and then an interest taken in an item being transported on Stone’s ship. Beckett is looking at the psychology of people who prefer to spend long periods of time in space but it isn’t the journey that’s the crux of this story. Worth a read.

“The Figure In Motion” by Steve Rasnic Tem gives us one man’s story. His name is never given but we soon learn that he’s a widower with time on his hands. To deal with this he creates an activity for himself at a local art museum which leads to unforeseen consequences. This story was not quite my cup of tea.

“Are You Sannata3159?” by Vandana Singh is a story about a future India, a future where class lines have become very distinct. Jhingur, a young man, works in a video shop selling opportunities for escape to other people. He’s at the bottom end of the socio-economic scale and when he isn’t looking at videos himself he finds himself looking at the towers above him – places where he can’t go.

In Jhingur’s inner world he imagines himself as much of a hero as the ones that he finds in the videos and this is what grinds against the realities of his existence. Singh, in the end, does justice to the character, which I appreciate.

Time travel is a genre all on its own in Science Fiction. Time travel stories often feature dinosaurs, mad scientists, cutting edge science and a mad dash for the MacGuffin (A nod to Alfred Hitchcock here). In “The Time Traveller’s Breakdown” by Gregory Norminton a time traveller takes a trial run with his machine, only ninety years, and suffers a mishap. With his time travel machine damaged beyond repair he must make his way back to the future he left behind one day at a time.

Norminton treats the story more as an allegory. The time traveller has a destiny, but how will he realize it, living in the same area where he grew up, without creating a paradox? The story answers that question, although the solution might disappoint the reader. Still, I have to commend Norminton for giving the story integrity. Worth a read.

Barbara is a housewife; her husband, Raymond, is a mailman and his boss, John, is coming over for dinner with his wife – what can be more banal? “Pillar Of Salt” by Robert Swartwood allows us to be a fly on the wall at this dinner and to hear a story of a letter being delivered to the previous occupant of their house, who was also a postman. He suffered dire consequences when he opened a letter which was addressed not to him, but to a man named Jonas Cotton. If any letters bearing that name do turn up they must be turned over, unopened, to John.

It sounds simple enough: just don’t open the item, but along the way we learn of the problems with the marriage, things that happened in the past and so forth. Before the story ends we know a lot more about Barbara’s motivation. There’s also a twist here. I sort of liked it.

The world has been taken over by robots and their biggest enemy is oxygen, for oxidation leads to rust. The human race is gone save for one survivor and he lives on a piece of real estate, full of trees, that can’t be destroyed.

The forest is named Wildewood and its human inhabitant is called Mr. Hallward. D-350, the hero in this story, has been given the task that so many before him have failed at: to eradicate Hallward and with it Wildewood. “The Forever Forest” by Rhys Hughes gives us a wry, comical look at a world containing robots with more than a few nagging problems.

Hughes can be funny and he gives the reader a nice puzzle to solve. Definitely worth a read.

Tom Hilton, the narrator of “The Farmer’s Wife” by James Cooper, is taking an almost sentimental journey to the Gudicci farm, a place he hasn’t been to in years. He’s going specifically to speak with Mrs. Gudicci, the mother of his childhood friend Jed. Tom has a specific agenda for his visit, but isn’t entirely aware of what is motivating him.

Tom was once very close to Jed and the Gudicci family. He shared in the wonderful home cooking but also witnessed the violence that Mr. Gudicci levelled at the people he was supposed to love the most. Cooper’s characters have been holding things in for years and it’s time for them to come out. It’s a very sensitive look at a small group of characters.

“Pages From An Invisible Book” by Darrell Schweitzer starts with a gathering of both the living and the dead. The ruler of a huge empire has died and a successor must be chosen. As part of the ritual the dead lords of the past rise from their graves and join the living in an appointed place for the choosing of a successor. Lord Yandos arrives with the others, like them he’s masked and it can’t be determined if he’s one of the living or one of the dead. It’s not clear to anyone what part he has to play until he wanders away from the gathering.

Schweitzer creates tension between the ritual, the naming of a new ruler, and the characters who stumble into the scenario. It is worth a read.

Noluthando Ngobo Bhele is the narrator in “Of Hearts And Monkeys” by Nick Wood. In this story Bhele is on a journey. The place is South Africa where some type of catastrophe has occurred. Bhele is among a small group of survivors who are fleeing towards the coast under constant threat of ambush.

Bhele alone can see the dead that follow them, try to warn them of danger or influence her actions. Wood’s characters, particularly Bhele, make the story worth reading.

Peter Hardy takes a long hard look at an urban legend in “Drive-In.” In it, Jim, a young, new in town professional is taking Julie on their second or third date to the Moonlight Drive In. Once there some memories return for both of them.

Vehicles arrive at drive-ins containing mostly families or couples and there are rituals that must be observed before the film ends and they leave. There are trips to the concession stand, the washrooms and to a play area for the children, away from the cars. Children scream, shout and run into the night, but what happens to them? Some people don’t go to drive-ins just to watch a movie.

I have to confess that I love stories with drive-ins in them and I had to finish this one.

“The Rescue” begins in a mental hospital with a patient high on drugs and trying to reconnect with reality. The hospital is dangerous – the staff are just a little too jack booted to make anyone feel comfortable. Holly Phillips describes the journey of a woman who is rescued from imminent death but then put into a situation almost as baffling as the drug induced state that she started in. Worth a read.