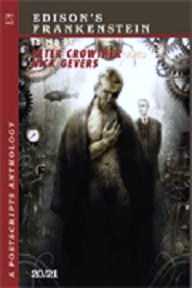

Edison’s Frankenstein: Postscripts 20/21

Edison’s Frankenstein: Postscripts 20/21

Edited by Peter Crowther & Nick Gevers

(Pub. date, December 2009)

Closing out Postscripts magazine for 2009 (now a bi-annual hardcover anthology) we asked Steve Fahnestalk and Kathleen M. Kemmerer to divide the twenty-six stories in this double issue between them. Steve reviews the first thirteen and Kathleen the final baker’s-dozen, many of which they found to be highly rewarding.

“Edison’s Frankenstein” by Chris Roberson

“The Dream Curator” by Alex Irvine

“Vampire Electric” by Tony Ballantyne

“The Healer” by David Hoing

“90 Share” by Jim Trombetta

“Denny” by Kit Reed

“Unreasonable Doubt” by Simon Strantzas

“Snowman’s Chance in Hell” by Robert T. Jeschonek

“Black Fragmentaria” by Michael Cobley

“Soror Mystica” by Uncle River

“The Love-Craft” by Lavie Tidhar

“Tests” by Robert Reed

“Killing The Dead” by Ian Sales

Reviewed by Steve Fahnestalk

“Edison’s Frankenstein” by Chris Roberson was, the author tells us, sparked by the idea that Tom Edison had made a film of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, not by the film itself. (If you’ve seen the Edison film, it’s quite clever for such a short movie—and the creature is so different from Karloff’s Monster.)

The story is set at the time of the 1893 Columbian Exposition, in Chicago… but there’s a major difference here: electricity is a minor trick, a toy, in this world, where “prometheic energy” rules. It seems that in the early years of the 19th century, an explorer named James Clark Ross returned from an expedition to the South Seas and brought back a piece of some broken automaton created by an antediluvian culture; and there was a tiny bit of the automaton’s power source left in the piece… and one of the fascinating things about prometheum, as it came to be called, is that if you expose it to charcoal it creates more prometheum. And the whole culture of the late 19th century is based on prometheum instead of electricity—except for a few diehards, like Thomas Edison, who keep experimenting with it.

The narrator is an expatriate Algerian Muslim named Chabane, who is bodyguard and translator for Sol Bloom, who runs the “Algerian Village” concession outside the fairgrounds, where all the lesser exhibits (like Bill Cody’s “Wild West Show” are banished). But something is afoot at the Exposition, and it may be murder, or even grave robbery! And an unknown man, who looks like the Algerian who drowned in the Lost Lagoon (“He has Salla’s eyes!” insist the women) has shown up, naked and covered with broken glass. Strange doings indeed at the 400th celebration of Columbus’s discovery of the New World.

Roberson has done a marvelous job of recreating not only the lost glories of that amazing exhibition (if you Google it, you will see how awesome it was) and the US of the late nineteenth century, but also a parallel world which is very close to, but not quite like, our own. Not to mention the different culture of the Algerians and the character of Chabane, who is pretty much treated like dirt by the Americans (a part of our heritage I hope we’ve finally started getting over). The mystery is, however, not exactly a secret or a mystery, as we’re told by the title of the story what’s going on. And the story is spoiled very slightly by the almost-jocular last line, without which I would have recommended this story unreservedly. (Note to story’s editor: I absolutely hate the neologism “alright”—why can’t you use “all right” instead?)

“The Dream Curator” by Alex Irvine concerns a strange little man who is responsible for all the exhibits at the Museum; he reports to (but is hardly guided by) the Nine Benefactors who are the Board. The Museum’s various wings (the Writers’ Wing, the Children’s Exhibit, the Maladies and Afflictions wing) are what brings in the investors, and the Benefactors want the Curator to follow popular trends… but the Curator has been there a long time and knows what the public really wants, and perhaps what it needs.

He needs dreams too; he is secretly misappropriating certain funds to gather a series of exhibits in what he deems the Blue Quiet—a secret wing for his eyes only. And maybe the Curator is starting to lose it a little bit, as the Blue Quiet begins to occupy his every waking thought that should be taken up with rearranging the various dreams to keep the public happy. A strange little story which is somewhat out of our experience—but the emotions of the people involved are familiar nonetheless. A good, if somewhat odd, story.

“Vampire Electric” by Tony Ballantyne concerns a world where the Vs, as they are called, basically drift through our society doing what they like, having their odd version of fun without knowing or caring what the effect is on ordinary humans. They apparently control a lot of our society, but Victor, the protagonist, is kind of cool with that. He even lets the only vampire he knows (Davina) watch when he makes love to his girlfriend. The other part of this strange world is that green and yellow wires apparently grow anywhere… and they have something to do with the Vs and the control they exert over humanity.

Victor is a keyboard player, and his friend Eric plays the electric violin. And Davina (the V) plays the electric guitar. So they’ve got a little group going, and Eric insists they play the kind of music that the Vs have banned. He’s doing the rock musician rebellion thing, and seems to be getting away with it. Until he learns he’s not. The locals call him (and his type) “hippie” and tell him to be cool with working for vampires, living in vampire-owned houses and generally being subjugated by those who used to be human. But Eric will have none of it.

There are a lot of subtleties in this story that aren’t explained, but it works well in spite of that. I kind of liked the vampire rock guitarist imagery (sort of a Dusk Till Dawn vibe). (Note to editor: again with the “alright” business. Learn some English, please?)

“The Healer” by David Hoing tells us about Ostil, a Drun who lives in Rykja, an abandoned Lithian village. The Drun are a very strange people, because when they reach a certain age, they have a fever and lose almost all their memories. After the fever passes, they can be retrained to do simple chores, and live simply—but no aged Drun is ever what he or she used to be before the fever.

The fever takes an hour or two to reduce what was once an intelligent teenager to an oblivious lump; and Ostil’s best friend is going to the ritual before him. Ostil knows that every single Drun who ever lived will go through this, so not only will he lose his best friend today, but soon he himself will lose his very self. But there are rumors of a healer, someone who can keep the fever from taking everything away that makes the Drun human.

Whether the “cresyn” healer can actually do what is claimed, and whether Ostil wants to stay the way he is, form the core of the story. This is an extreme version of what happens to people during adolescence, isn’t it? Don’t children (and teenagers) insist that we adults are alien beings who are somehow duller than they are? Knowing it’s coming, would you, like Peter Pan, prefer to be a child all your life, or would you metamorphose into something that the younger self wouldn’t recognize?

A really good story.

“90 Share” by Jim Trombetta is a kind of a fun throwaway, though it’s told in a serious tone. Peirce works for one of the major networks, but the execs don’t like his political views, so he’s been exiled to a popular science show beat. But that means he’s the man on the spot when a possible alien tomb is found in the Sahara.

Although the blue-skinned natives (their robes are dyed with a dye that runs and stains their skins) insist that to open this tomb would be disastrous, Peirce knows that this is the Big One that will make his career. What happens when he finally gets the world-beating 90 share (the share denotes the percentage of the possible audience worldwide that’s watching) for the unveiling? I’ll let you read it and find out. Minor, but well done. (More fantasy than SF, however.)

“Denny” by Kit Reed is another cautionary tale about adolescence and what can happen if you get too afraid your kid is headed towards another Columbine. Don’t get me wrong, I love Kit Reed’s writing, and have since Armed Camps in the late ‘60s and “Attack of the Giant Baby” in, I think, F&SF. She’s an excellent writer of both novels and short stories—but there’s really nothing SFnal in this story. It’s a good story with a nice kick, but not genre.

“Unreasonable Doubt” by Simon Strantzas is a ghost story, and not quite a traditional one. Dr. Reggie Reilly is a doctor in Hamilton (Ontario?) and his old friend Alistair Burden, who had once run for mayor of that town, is back and wants his help. You see that Alistair had almost been run out of Hamilton years ago because although he was never convicted, the whole town is convinced that he killed his wife and her lover, although it was ruled a murder-suicide.

And now he’s back in town and wants Reggie’s help because he’s being haunted by the ghosts of his dead wife and her lover and he has nowhere else to turn. Although this story is competently written, there’s really not much that lifts it above the common run-of-the-mill ghost story except, perhaps, the ending, in which Reggie learns some of the costs of friendship. Good, but not a great story.

“Snowman’s Chance in Hell” by Robert T. Jeschonek is another fun little story and, like the other “fun” one I cited, not written in a humorous way—well, I guess that would depend on your sense of humor—but with a blackly funny core for a nasty, cynical type (which I guess I am). You see, snowmen once populated the whole world, until one, named Wink, created the first “meat” man.

The meat man, named Hurt, lived up to his name by creating fire, a thing previously unknown in the world of snowmen—and something so injurious that Hurt and his fire have killed almost all the snowmen there are. But Hurt is tired of living alone and, like Frankenstein’s monster, wants his creator to make him a companion. I think you’ll enjoy this bizarre little number, which has just a bit of a poignant little frisson at the end.

“Black Fragmentaria” by Michael Cobley takes place in a time far past our own, where what was once called Caledonia and is now Glasedin, hub of the Northern Empire, is ruled by three houses: Obsidian, Pearl, and Iridium. (There was once a fourth, Adamantium, but it was erased in nine bloody days, and now only the Emperor Nox remembers it and the Urquharts who once ruled.)

If you enjoy the writings of such people as Jack Vance, you’re probably going to like this one a lot. I enjoyed the idea of a “redactor”—something that can erase past time and past actions. This is the story of how the populace rebelled against the Emperor’s rule and whispered of a savior named “Orkheart.” What happens next is not quite what either side expected. This is somewhat densely written, quite literate, and has almost an Avram Davidson vocabulary. Quite a well-told story. And it has a sort of “steampunk” feel to it, as well.

“Soror Mystica” by Uncle River is hard to describe. It concerns one Sean LeDoux, mystic and motorcycle rider, who comes to the little New Mexico town of Becky’s Ham, where he meets up with Lizbeth Langtree—Goddess of the DIA, the Department of Institutional Adherence—who has the power to deny, demote, obfuscate and destroy any governmental application, including job applications, that cross her desk.

Imagine R.A. Lafferty on speed (or visualize him the way he was always seen at conventions, on booze). Now cross him with Chester Anderson (The Butterfly Kid) and throw in a dash of Hunter S. Thompson. Now write a really short version of either Gone With The Wind or The Odyssey, I can’t really tell—no, wait, something by Kinky Friedman—or maybe it’s Farmer Giles of Ham. Or maybe Sean is The Devil or his opposite.

And there you have “Soror Mystica,” I think. You’ll have to read it yourself—but beware, it’s probably not PC. Whatever it is, I enjoyed it.

“The Love-Craft” by Lavie Tidhar is a short story told in screenplay fashion. It’s recommended for mature audiences and with good reason. Imagine a “women in chains” movie mashed up with a flying saucer/alien abduction epic and a Lovecraftian sensibility. It’s funny, sexy (but not the least bit erotic) and pretty literate as well. And it may be the first sf or fantasy story I’ve read in a good many years that relies on pidgin for one character’s speech—not the least of which is that pidgin is probably non-PC these days. (Pam [one character] says “…he stickim something long ass blong yu mekem experimen” which is very funny in a “South-Sea Islander of the early 20th century meets probing aliens” sort of way.)

I can’t tell whether Adam (the main character) and his wife Lilith (yes, it’s probably his first wife, Biblical scholars) are actually living the abduction screenplay, but it’s a workable hypothesis. But when all is said and done, Adam says “life ties you up, and effs you up, and then…” you’ll have to read it to find out. I thought it was well done and funny.

“Tests” by Robert Reed was, like all Reed’s fiction, well written, but I didn’t buy it. First off, I don’t buy his hypothesis of anthropogenic global warming. The jury is, despite all protestations to the contrary, still very much out on this, though the verdict is increasingly looking like it’s a thumbs-down. So using that as a key point doesn’t work for me. I agree, SF writers are always on the bleeding edge of what’s possible, but this one bleeds more than most.

That being said, there’s some very interesting stuff in the story. Did you know that SETI detected a signal in the early ‘70s that was so convincing it was dubbed the “Wow” signal? It’s true—but it’s never been detected again, despite 30 years of searching. And did you know about the hawks/doves scenario in which it’s argued that warlike alien cultures would not be able to survive in a universe dominated by peaceful ones, because it’s so easy to use an asteroid to destroy a hostile planet?

So given the fact that the universe is probably full of intelligences, why have we not been contacted before this, openly? Read the story yourself and, if you’re able to swallow the anthropogenic warming hypothesis and at least one other dubious one, you may like the story which, in spite of its flaws, has a positive thrust (if you’re one of the 10% of humanity that survives after one scenario). I liked the writing, but not the hypotheses. Yes, it would be possible for us to deliberately tip our climate the wrong way, but I think it would be harder than a lot of people believe. Not really recommended by me. You may like it.

“Killing The Dead” by Ian Sales concerns a generation ship on the way to another star, HD209458. From what the author has written, it appears to be on the model of a habitat, such as have been proposed for our Lagrange points; imagine a long capsular cylinder with habitations, factories, fields, etc., lining the inside of such a cylinder, so that if you looked up from the inside, you’d see your opposite looking down at you. Now imagine mastery of cryogenic technology (or something similar) so that the dead can be certain to be awakened at some time in the future. Under those scenarios, you can see that, as inhabitants of the generation ship die, there will be more and more space and resources devoted to maintaining their bodies for the resurrection to come.

Inspector Dante Arawn is investigating another vandalism report. Someone is destroying mausoleums (necropolises) and the ship is going dark. Why are they doing this? What reason could terrorists have to want to prevent the ship from reaching its destination? And is Constable Supay, who works for Inspector Arawn, in league with the terrorists?

The conclusions that Arawn comes to and the reason for all the bombings make sense in the context of the journey and of the story. I particularly liked this story as it was pure SF that couldn’t happen in a different context; that is, the reasons for the terrorism could only exist at that time in that place, and the arguments for and against made perfect sense in context; as well, the Inspector’s conclusions were in keeping with his personality and his role aboard ship. Highly recommended.

“The Horse Angel” by Marly Youmans

“The Winding Down Of The World” by Rjurik Davidson

“The Persistence of Memory, Or, This Space For Sale” by Paul Park

“’Seng, Running” by Darin C. Bradley

“Catherine My Lionheart” by Allen Ashley

“O King of Pain and Splendor!” by Darrell Schweitzer

“Hand Scratched Note” by Catherine J. Gardner

“Time Changes” by David T. Wilbanks

“Another Day In Fibbery” by Matthew Hughes

“Ragged Claws” by Lisa Tuttle

“The Denham Inheritance” by George-Olivier Châteaureynaud

“Number One Fan” by Eric Schaller

“The Phoebean Egg” by Stephen Baxter

Reviewed by Kathleen M. Kemmerer

If you like urban fantasy, “The Horse Angel” by Marly Youmans has a haunting quality to it. It takes the form of two dramatic monologues by two very different characters, both likeable and heroic in the midst of emotional pain. After a few minutes of confusion as I began the second monologue, the story worked for me. It is a compelling story of hope and healing.

The first monologue is Elsbeth’s. She is an elderly widow who has lost the love of her life, her husband of 63 years, Edward. Her children want her to leave her ancestral home and live at the Thanksgiving House, “like a folded cloth in a cupboard.” This suggestion hurts her deeply because this home she shared with Edward embodies her memories and her connection to her ancestors. She confides all this to Mary Russell, a neighbor, and she asks Mary to promise on her mother’s memory to keep a strange secret – that an angel comforts her by its presence every night, an angel in the shape of a horse. Elsbeth’s joy is renewed by the angel’s nightly visits. As proof of her story, she shows Mary the feathers collected from its wings.

The second part of the story is Mary’s narration. She is a nineteen-year-old with a tragic past whose stepfather used to beat her and had finally beaten her mother to death. Mary had been rescued by Gabe, first from the beatings and then from being placed by a social worker with her aunt and uncle which Mary had feared because her uncle had incestuous relationships with two of his three daughters. Gabe, a young man from a wealthy family, had fallen in love with her, and saved her by marrying her with his parents’ blessing. Although she seems to love him, an element of doubt seems to linger since she longs for love as enduring as Elsbeth’s and Edward’s. Her hesitation to believe Elsbeth’s unlikely story evaporates when she sees the feathers, and she finds herself coveting a feather strongly enough to want to steal one. Fortunately, Elsbeth gives her both a feather and a book on birds that tells about feathers. A glimpse of something that may have been a horse in Elsbeth’s garden in the first hours of the next day thrills her, and she sings to the Horse Angel. But her song is not beautiful as she would have liked, she sings badly the song that her stepfather used to taunt her mother, tying the beautiful moment to the pain of her past.

The epigraph of the story comes from “Air and Angels” by Donne about the difficulty of understanding the purest essence of love since we are embodied creatures and can only see love embodied in another, as pure angels can be seen only as a shape in the air, a substance less pure than their essence. This is a story about love and healing. The Horse Angel is an embodiment of comfort and hope, a cause of intense joy which heals two women who share the secret of its existence.

The story is complex and rich, an enjoyable read.

Psychological horror is the name of the game in “The Winding Down Of the World” by Rjurik Davidson, a story about a man trapped in a hell of futility and existential angst worthy of a Twilight Zone episode.

The first-person narrator has difficulty relating to others and perhaps to reality itself. His extreme narcissism colors the world with his sense that the world is, well, “winding down” to its end so that he is trapped and not able to accomplish anything constructive. He has no real relationship to Simón, the man with whom he shares an apartment. They repeat the same meaningless phrases to one another daily without really connecting. He similarly fails even to have a conversation with his elderly neighbor, Mrs. Eden, who, it may be granted, is not a great conversationalist herself. His first meeting with a tattooed woman in a ladies clothing shop is characterized by disjointed attempts to pick her up after he watches her dress a mannequin while talking to it. He becomes obsessed with her hard thighs and smooth skin. Her tattoo, in a Gothic font reads “Discrimen,” a Latin word meaning “crisis, division, or difference.” When she takes him to her apartment, it is populated with mannequins dressed in 1920s style that she introduces to him by their names. The next day, he takes Simón to the shop to see the woman, but Simón, who enters the shop by himself, returns saying that no one is there. Then, he announces that he is moving to Chile and leaves. When the narrator enters the shop, she is there, and he decides she must have been in the back room while Simón was in the shop. He goes to her apartment to wait for her to get out of work.

A mishap with one of the mannequins whose arm comes off in his hand inspires him to take all of them apart and interchange their parts and attire. When she sees this, the woman is shocked and angry at his desecration. She slaps him and then suddenly begins making love to him. I won’t spoil the ending, but back in the day, Rod Sterling might have bought the rights to this one.

There are repeated echoes of William Butler Yeats’ “The Second Coming,” “things fall apart; the centre cannot hold.” However, instead of the anarchy, dynamism, and intensity that characterize the poem, the feeling is more like the interminable waiting and sick futility of a Samuel Beckett play.

“The Persistence of Memory, Or, This Space For Sale” by Paul Park is a light, distinctly post-modern story that has the delicious audacity to turn the metafiction on its head. As you may know, especially if you are a literature geek or have the odd Ph.D. in English, metafiction is a “story within a story” that calls attention to the fictional nature of the narrative – think the Schwartz light-saber fight in Spaceballs where the stage lighting is knocked over and the cameraman is killed or the grandfather reading the story of The Princess Bride to the sick kid. Yep, that’s the stuff.

Park’s author-narrator takes the reader behind the scenes of writing the story where he reveals that most of the story’s major elements have been auctioned off on e-Bay, with the winners determining the type of story, the title, and the characters. The narrator-author’s secret favorite is an underdog, the unnamed, lovesick boyfriend of Sarah Kettle who “was hoping to find some kind of special way to tell her how I still feel, even after some time.” Another high bidder, who had, in fact, outbid the underdog hero in one of the auctions, is Ben Burgis whom the narrator decides to use as a zombie or psychopathic villain who menaces Sarah.

In the course of learning about Sarah to be able to do her character justice, the author-narrator becomes increasingly obsessed with her. Finding himself in the city and neighborhood where she lives, he decides to take a look at her house for descriptive purposes. The ending is a surprise, so I won’t spoil it, but, in effect, the e-Bay auctions stand in for the real relationships among the characters in both the “story within the story” and in the narrator-author’s “real life.”

This is a delightful example of post-modernism. Literary anthology makers, take note: this story would enliven any course on the post-modern.

Another urban fantasy with a very different feel than that in “The Horse Angel,” is Darin C. Bradley’s “’Seng, Running.” The first-person narrator is involved in the black-market harvesting and trade in wild, North American ginseng, or, as he refers to it, ‘seng. It is a fact that ginseng, a slow-growing perennial, is difficult to cultivate, so the high prices brought by mature roots in Asia have threatened the survival of ginseng in the wilds of North America. The roots of a plant 10 years old or older, yellow in color, and shaped like a person are rare and are most in demand. As a result, many states regulate ginseng harvest on state lands and in national parks, and the penalty for circumventing these regulations includes jail time.

To support his desperately poor family and to supply them with ginseng, the narrator is drawn ever deeper into black market activities. With Evan, a local known for his involvement in poaching ‘seng on public lands, the narrator risks his life and freedom to harvest the precious roots. The fantasy element of the story revolves around the behavior of the “manroot.” This is an enjoyable and unpredictable story.

“Catherine My Lionheart” by Allen Ashley could credibly be classified as science fiction; however, it is a languid tale with a dreamy cast, more romantic Goth than horror, and more a character study or vignette than a fully plotted fiction — perhaps best read with a glass of wine and the Cure playing softly in the background.

The tale revolves around the mutual flirtation of a tax accountant with his much older client, an aging, agoraphobic musician and actress. Who said accountants were boring? Strongly attracted to her, almost hypnotized, the intrepid accountant narrates self-consciously, describing and gloating voyeuristically over each scene as Catherine strikes poses for his benefit. He feels the tug of this lethargic (almost vampiric) seduction, but also feels a little guilty that he has been taking advantage of the situation, letting her cook for him and tell stories from her glamorous past as he watches her pose. All this is set against a backdrop of theatrical costumes and movie props, including a full torture chamber where he discovers her secret. For me, the ending fell a little flat. But this story is more about the mood than the plot, and the mood could not have been sustained regardless. I will only assert that no accountants were harmed in the making of this story.

The long-lived sorcerer Sekenre makes a return appearance in Darrell Schweitzer’s “O King of Pain and Splendor!” a sword and sorcery story. The core of this tale is the alternate reality/history of King Vashru, the second. As the depraved king of the title, Vashru is cruel, killing and torturing at whim, murdering even his wife and sons, save only his idiot son whose lack of ambition is appealing.

Sekenre shows him an alternate life in which he never became king. His alternate self is an ignorant, poor boy, “Little Vashru.” This alternate self hates violence and knows only love and hard work until his mother is killed, his sister is raped, and his pregnant wife loses her unborn child and her mind.

At this crisis, Sekenre asks him whether he is the king dreaming that he is “Little Vashru” or “Little Vashru” dreaming that he is the king. In his desire for vengeance on those who harmed his family, “Little Vashru” chooses to be the powerful but depraved king. However, as king, he must face what he fears most, the god of death. In the end, Sekenre saves Vashru’s surviving son and weeps for “Little Vashru.” The plot is a good deal more complex than this, vexed by Sekenre’s uncanny ability to shift out of time.

At first, I was disappointed that this epic tale deals in stock characters, the wise Sekenre whose existence outside of time gives him an impossible foresight and wisdom, the innocent “Little Vashru,” the completely wicked Vashru, the second. However, as I read, the story and characters gained depth. It is greater than the sum of its parts, and ends up showing the complexity and duality of human nature in a way that I had not expected. This is a must-read.

Catherine J. Gardner’s quirky horror short, “Hand Scratched Note” is set in and around the Graveyard of the Forgotten, where a boy named Ghost meets and falls for a Goth girl named Marie Pickens, a girl with a third eye that she claims allows her to see ghosts. To her great delight, when she asks if he is dead, he says that he is, and the rest is a series of strange, sad coincidences as unlikely as they are macabre. This is an enjoyable story that entertains and then continues to haunt the imagination.

A second horror short, “Time Changes” by David T. Wilbanks, is very different but also very enjoyable. Set in a costume store, the first-person narrator tells about an odd customer who bought a clown costume. Since telling too much about the story would spoil it, I’ll stop here. Just add it to your list knowing that, if you like horror, this one’s for you.

Luff Imbry, a food-obsessed art thief, forger, and master criminal of Old Earth’s penultimate age, makes a return appearance as the main character in Matthew Hughes’ science fiction story “Another Day In Fibbery.” Although it is set on Earth in an unspecified future time, the story is timeless. It could have been plucked in Aladdin’s Bagdad with high tech flying cars instead of flying carpets or placed in the back streets of some exotic location today. The sausage-fingered Imbry bribes a guard to steal a relic and is unexpectedly attacked by a “Disciplined Aspirant” of the “Community,” a fanatic religious organization. Once he extricates himself from this predicament by killing the would-be killer, he finds that he now possesses not just the relic, but a very rare item, the Aspirant’s entourage, a mollusk shell case in which the believer kept trophies of his victims so that they might serve him in the afterlife.

On his way to sell these ill-gotten gains, Imbry is accosted and taken captive by the employees of a loan shark to whom he owes money. Caught between the practical loan shark who plans to make an example of him and the vengeful brothers of the “Community,” Imbry’s sharp mind and fleet feet find a way out of danger. The story is richer and more complex than I can convey here. This character and the world he knows so well is a delight from start to finish. This is another gem of this issue.

The first-person narrator of Lisa Tuttle’s science fiction story “Ragged Claws” is a highly complex character at once passionate and ambivalent about recruiting young people to sign on for the decade-long trip to Earth’s distant colony of Eden. Having spent ten years working on the research for the time in flight, herself a guinea pig in a life pod, experiencing a cyber recreation of what living on Eden would be like, recruiting is how she makes her living.

This story is about one encounter in a bar with three young people. The girl, Blake, is interested; her male companions have many objections to the idea. The source of the narrator’s ambivalence about and even reluctance to recruit is hard to pinpoint. She herself says, “If it weren’t for the bloody Eden Corporation’s effen age restrictions, I’d sign up right this minute. I’d leave tonight. And I’d gladly spend my next ten or eleven years in a box, knowing I’d climb out on Eden at the end of it, even if I knew I’d drop down dead at the end of my first week there. I’d take that chance, just to have that one week. That’s how much I loved it.” And yet, the narrator feels sympathy for Blake that she pushes aside out of need for the money that the girl’s recruitment will bring.

The title is from T. S. Eliot’s famous “Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” near the end where the impotent Prufrock, lonely and unable to enter into a conversation with the young ladies at the party, says, “I should have been a pair of ragged claws /Scuttling across the floors of silent seas.” Tuttle’s main character shares Prufrock’s feelings of uselessness and the frustration of recruiting others to do what she most desires to do. I found the character very appealing in her humanity. This was one of my favorite stories.

“The Denham Inheritance” by George-Olivier Châteaureynaud might be classified as a historical fiction. The story is translated by Edward Gauvin. The sidebar for this story does not mention an earlier publication date, so I deal with it here as its first English appearance.

The story itself narrates a sequence of coincidences that result in the translation of poems inscribed in unknown writing on banana leaves found in the cellar of a deceased war correspondent. The heir’s girlfriend discovers the leaves and sends them to her grandfather to console him for her absence over the holidays. The grandfather, Adrian Moon, an elderly professor of primitive aesthetics, receives the leaves on Christmas Eve. Suspecting that they may be a form of writing rather than art, he contacts a linguist friend who eventually deciphers them; however, the death of the war correspondent and the granddaughter conspire to keep the provenance of the writing a mystery. The rest of the story is a letter from the linguist to Professor Moon with a translation and commentary on the story the leaves contained.

With its strong similarity to detective fiction, this was an enjoyable and interesting story; and although not at the top of my own list of favorites, the canny reader may find it has much more to recommend it than I have mentioned.

Eric Schaller’s “Number One Fan” is a tongue-in-cheek horror story that takes a satirical swipe at authors who attend SF conventions. Knowing the convention scene is not necessary to enjoying Schaller’s humor at the expense of authors’ egos.

Paul Slade, an SF author, booked to read his work at Cosmi-Con, searches seemingly in vain for Room 6. When he finally finds it hidden away in the basement, the room is occupied by a single highly unattractive fan, who is annoying to say the least. At each step, Slade reaches a new level of loathing for the man as he repeatedly foils Slade’s attempts to escape the room, insisting that Slade read for the entire hour-long slot, while the fan passes in and out of slumber, snoring loudly. Eventually, however, Schaller’s hero is reconciled to the fan whose overflowing backpack contains everything Slade had ever written. It turns out that this loathsome fan planned the entire conference for Slade’s benefit, simply to hear him read a composition Slade had written while still in grade school. The ending is an uncanny horror twist that will leave you smiling and perhaps, if you also write, shuddering.

Stephen Baxter’s novelette “The Phoebean Egg” is an engaging alternate history/science fiction story that ends the issue with a solid bang.

The story is set in a nineteenth-century British Empire that has conquered nearly the entire planet by its possession of Anti-ice technology. Cederic Stout, a young man from a family that has been displaced by surface mining for coal in Northumberland, has been recruited by the prestigious “Academy of the Empire,” where the Empire’s best brains are educated in the hope that they will help to keep the Empire strong through technology. Cederic, Merrell, and a servant girl named Verity Fletcher secretly incubate a Phoebean Egg, and care for the strange hatchling that Verity longs to return to the Earth’s second moon so that it can be with its own kind. They use the drilling machine that Merrell had invented to break into a secret installation at the edge of the Academy’s property where they interrupt work on a secret project and get into trouble with the headmaster. In doing so, however, they come to learn from Fitzwilliam, the Academy’s bully and math whiz, that the secret project that he and some of the students have been recruited to run calculations for is an Anti-ice missile that the King plans to use to force a Pax Britannica on all the nations of the world. The four young people set out to foil this plan, and I leave their inventive solution for you to discover on your own.

The characters are likeable and intelligent. The pacing of the story and quality of the dialog are just right. Even minor characters like Fitzwilliam and the headmaster have enough complexity to be satisfying. Characters discuss the Anti-ice weapons in language not unlike that of the historical nuclear arms race, saying that Anti-ice weapons would be horrific enough to be a deterrent to war – a premise we know to be false. The story also points to the stupidity of gender and class prejudices that doom Verity to the role of a servant when her intelligence and creativity make her better suited to be a student at the Academy.

Baxter combines historical knowledge of the time, scientific inventiveness, and believable characters to make this my favorite story in a list of strong candidates.

This is a collection to savor. Nearly all readers will find something to love here.