The Life of Riley (1944-45, 1945-51) aired “Two TV’s for Father’s Day” on June 16, 1950 as the 284th of its 324 programs. The 1944-45 run (January 16, 1944 through July 8, 1945) was broadcast by the Blue Network (later to become ABC), while the show was picked up for the remainder of the 1945 season (September 8, 1945 forward) until its final show on June 29, 1951 by NBC.

The Life of Riley (1944-45, 1945-51) aired “Two TV’s for Father’s Day” on June 16, 1950 as the 284th of its 324 programs. The 1944-45 run (January 16, 1944 through July 8, 1945) was broadcast by the Blue Network (later to become ABC), while the show was picked up for the remainder of the 1945 season (September 8, 1945 forward) until its final show on June 29, 1951 by NBC.

The show was originally pitched to the sponsor under a different title and with none other than Groucho Marx in the lead role. However, the sponsor rejected the original concept fearing the show would be just another “head-of-the-household” sitcom that wouldn’t be a good fit for Marx. Irving Brecher, the screenwriter who wrote for the Marx Brothers, undeterred, then pitched the idea with William Bendix (1906-1964) in the lead after seeing Bendix in 1942’s Hal Roach film The McGuerins from Brooklyn. With some revisions of the script originally written for Groucho and a new title, The Life of Riley was born.

The show takes place in southern California during World War II where Chester A. Riley is a working class wing riveter in the fictional Cunningham Aircraft plant. He lives in a modest suburban bungalow with his wife Peg, his son Junior, and his daughter Babs. Riley is a basically decent man, a good man with a kind heart. Aside from his family, other popular characters appearing from time to time are one of Riley’s co-workers at the aircraft plant, Jim Gillis (who inadvertantly ends up being the cause of a number of Riley’s misadventures), and Digby “Digger” O’Dell, the congenial undertaker who helps bail Riley out of holes he has dug for himself.

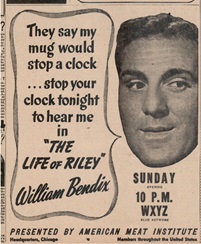

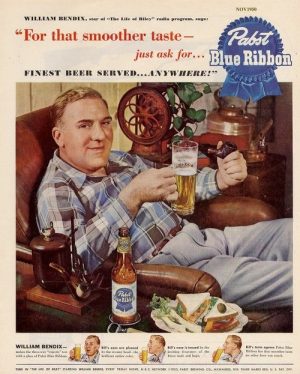

William Bendix also starred in the successful 1949 film with the same title as his popular radio show. The Life of Riley also ran on television for a single, 26-episode season from October 1949—March 1950. It ended after the 26 original episodes because Irving Brecher and the sponsor, Pabst Blue Ribbon beer couldn’t come to terms over extending the show for a full 39-week season. While at odds with Pabst Blue Ribbon as the television sponsor, the radio show was happily sponsored by The American Meat Institute (1944-45, the oldest and largest trade association representing the U.S. meat and poultry industry), Proctor & Gamble (1945-49), and the aforementioned Pabst Blue Ribbon beer (1949-51). Over the years the show would move to different times and days of the week, but remained popular with its loyal audience who followed it faithfully. This episode, for example, aired on a Friday night and ran from 9-9:30 PM.

William Bendix also starred in the successful 1949 film with the same title as his popular radio show. The Life of Riley also ran on television for a single, 26-episode season from October 1949—March 1950. It ended after the 26 original episodes because Irving Brecher and the sponsor, Pabst Blue Ribbon beer couldn’t come to terms over extending the show for a full 39-week season. While at odds with Pabst Blue Ribbon as the television sponsor, the radio show was happily sponsored by The American Meat Institute (1944-45, the oldest and largest trade association representing the U.S. meat and poultry industry), Proctor & Gamble (1945-49), and the aforementioned Pabst Blue Ribbon beer (1949-51). Over the years the show would move to different times and days of the week, but remained popular with its loyal audience who followed it faithfully. This episode, for example, aired on a Friday night and ran from 9-9:30 PM.

“Two TV’s for Father’s Day” is not only prescient in more ways than one but a chuckle out loud funny episode. The story revolves around Chester getting home from a hard day at the aircraft plant looking forward to greeting his wife and kids, having a nice meal, and relaxing in his comfortable home. What he gets is just the opposite when Junior, Babs, and wife Peg are off to the neighbors to watch Bob Hope on their new television sets, leaving Chester at home alone and grouching at his situation. While all of the promotions for the new invention swear it will bring families together, Chester sees his family gone to watch it at the neighbors, and swears there will never be a television set in his house as long as he lives. When his friend Gillis stops by and reminds him that Father’s Day is a few days away and his kids won’t remember him it sets Chester off on a bout of depression as he assumes an “I don’t get no respect” vibe. Timely observational humor and Chester’s thinking about his plight are well drawn, and the resolution (given away in the episode’s title) is well worth the wait, making this a well written slice-of-life sketch revealing Riley as a blue-collar working-class Everyman whose life centers around his family, balancing a real life situation with an eventual optimism that is hard to resist. In fact, Chester plays the “I don’t get no respect” angle so well I immediately thought of the late comedian Rodney Dangerfield, who made his living playing the same shtick to international success and fame. But Dangerfield began using his now famous line only in the early 1970s, and here we have William Bendix using the concept behind the line to full effect some 20 years earlier. Not that Bendix was necessarily the first, mind you, but just well before it became an iconic phrase many years before Dangerfield capitalized on it.

What really struck me about this episode, however, was the effect a new technology (the commercial television) was having on Riley’s family on a sociological level. We see the same dynamic that other new technologies have had on individuals and families today especially with the advent of the home computer, and even more pronounced with smart phones which are in effect hand held computers. Sociologists are already having a field day with the impact these technologies are having on our society, from the micro to the macro level, but the technological canary in the coal mine can be seen with other inventions, including the evolution in communication with the telegraph, the telephone, (the radio!) and in this episode involving the commercial availability of the television set. Some immediately embrace such technologies, while others stand against them, as happens with any new technology. Fortunately, Chester A. Riley, on Father’s Day, finally came around and saw the light as he received “Two TVs for Father’s Day.”

Play Time: 29:06

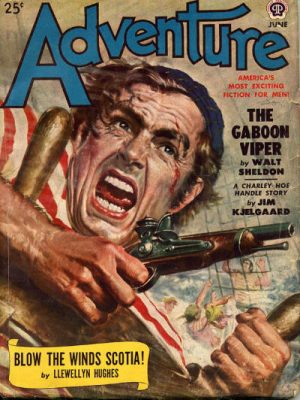

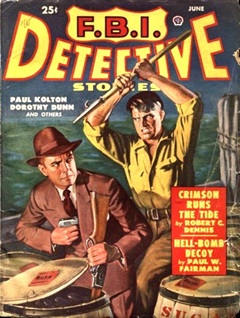

{This special Father’s Day episode of The Life of Riley aired at 9 PM on a Friday evening in the middle of June 1950. The various parents of the neighborhood gang had co-opted their respective family household downstairs radios to listen to this special show, Father’s Day being only two days away. Not being able to listen to one of their favorite detective programs made the gang more determined than ever to meet at the nearby newsstand the next morning in search of the kind of stories filled with action, adventure, and danger, the kind they couldn’t go long without. 5-Detective Novels (1949-53) featured classic reprints, much like Famous Fantastic Mysteries offered classic reprints of fantasy or science fiction novels before the advent of the true genre magazines. In the case of 5-Detective Novels it sourced its material from earlier issues of magazines from the 1930s and ’40s like Black Mask. Lasting only 17 issues, it was a quarterly during its entire run. Adventure (1910-71) was born to cash in on the popularity of magazines like Argosy whose circulation ran into the hundreds of thousands per issue. While Argosy and others of its ilk ran stories from many genres and interests, Adventure opted to focus its fiction on danger and excitement. It was a rousing success, but as times changed it eventually ended up as primarily a men’s magazine. 1950 saw 11 monthly issues. and in 1951 it switched partway through the year to a bimonthly. F.B.I. Detective Stories (1949-51) entered the crime fiction fray late, and found out soon enough that the trend in stories about the Feds was long passed, popular as it had been in the ’30s and into the ’40s in film, print, and radio. It managed but 14 bimonthly issues before turning in its badge for good.}

[Left: 5-Detective Novels, Summer/50 – Center: Adventure, 6/50 – Right: FBI Detective Stories, 6/50]

To view the entire list of weekly Old Time Radio episodes at Tangent Online, click here.