Philo Vance (1943-45, 1945, 1946-52) aired “The Ivory Murder Case” on March 28, 1950. The number of total episodes is unknown due to the lack of information on the 1943-45 run, though a good estimate combining the other two runs comes close to 120, though numbers vary. This is but the fifth episode of this well received program we have presented since 2018, the last being in September of 2020. For newcomers and for those needing to refresh their memories, we reprise (with minor variation) the initial background information.

Philo Vance (1943-45, 1945, 1946-52) aired “The Ivory Murder Case” on March 28, 1950. The number of total episodes is unknown due to the lack of information on the 1943-45 run, though a good estimate combining the other two runs comes close to 120, though numbers vary. This is but the fifth episode of this well received program we have presented since 2018, the last being in September of 2020. For newcomers and for those needing to refresh their memories, we reprise (with minor variation) the initial background information.

The character of detective Philo Vance was the brainchild of S. S. Van Dine (pseudonym of Willard Huntington Wright, 1888-1939, photo top right). Wright would pen 12 Philo Vance novels between 1926 and 1939, the first of which was The Benson Murder Case (1926) and the last being The Winter Murder Case which he finished shortly before his death in April of 1939. Vance was very much in the mold of the “gentleman detective” or what would come to be known as the “soft-boiled” variety of detective. He has much in common with Sherlock Holmes and Nero Wolfe in that he was in possession of a giant intellect, though his arrogance and aloofness surpassed that of the former detectives and put many off. As Wright himself wrote of his character (via Van Dine) in The Benson Murder Case: “Vance was what many would call a dilettante, but the designation does him an injustice. He was a man of unusual culture and brilliance. An aristocrat by birth and instinct, he held himself severely aloof from the common world of men. In his manner there was an indefinable contempt for inferiority of all kinds. The great majority of those with whom he came in contact regarded him as a snob. Yet there was in his condescension and disdain no trace of spuriousness. His snobbishness was intellectual as well as social. He detested stupidity even more, I believe, than he did vulgarity or bad taste. I have heard him on several occasions quote Fouché’s famous line: C’est plus qu’un crime; c’est une faute. And he meant it literally.

“Vance was frankly a cynic, but he was rarely bitter; his was a flippant, Juvenalian cynicism. Perhaps he may best be described as a bored and supercilious, but highly conscious and penetrating, spectator of life. He was keenly interested in all human reactions; but it was the interest of the scientist, not the humanitarian.

“Vance’s knowledge of psychology was indeed uncanny. He was gifted with an instinctively accurate judgement of people, and his study and reading had coordinated and rationalized this gift to an amazing extent. He was well grounded in the academic principles of psychology, and all his courses at college had either centered about this subject or been subordinated to it…

“He had reconnoitered the whole field of cultural endeavor. He had courses in the history of religions, the Greek classics, biology, civics, and political economy, philosophy, anthropology, literature, theoretical, and experimental psychology, and ancient and modern languages. But it was, I think, his courses under Münsterberg and William James that interested him the most.”

Unfortunately (or fortunately as is your preference), the radio and film portrayals of Vance toned down his aloof disdain for the common man and made him more likable for audiences. Speaking of the films, there were a dozen adapted from 1929 through 1940. There were a trio of later films made in 1947 but they had nothing to do with the novels and little relationship to the Vance character. Of the first five films (two in 1929, two in 1930–one being The Benson Murder Case, and the fifth in 1933) William Powell starred in four, while future Sherlock Holmes film star of the 1940s, Basil Rathbone, starred in the fourth (The Bishop Murder Case, 1930). The final Powell role as Vance came with 1933’s The Kennel Murder Case. Such was Powell’s popularity and connection with the movie-going audience that in 1934, barely a year later, he would co-star with Myrna Loy in the first of the classic films adapted from Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man detective novels and stories.

Unfortunately (or fortunately as is your preference), the radio and film portrayals of Vance toned down his aloof disdain for the common man and made him more likable for audiences. Speaking of the films, there were a dozen adapted from 1929 through 1940. There were a trio of later films made in 1947 but they had nothing to do with the novels and little relationship to the Vance character. Of the first five films (two in 1929, two in 1930–one being The Benson Murder Case, and the fifth in 1933) William Powell starred in four, while future Sherlock Holmes film star of the 1940s, Basil Rathbone, starred in the fourth (The Bishop Murder Case, 1930). The final Powell role as Vance came with 1933’s The Kennel Murder Case. Such was Powell’s popularity and connection with the movie-going audience that in 1934, barely a year later, he would co-star with Myrna Loy in the first of the classic films adapted from Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man detective novels and stories.

For the 1945 summer replacement series, native-born Puerto Rican actor (Tony {1947} and Oscar {1950} award winner, both for his portrayal of Cyrano de Bergerac) Jose Ferrer (1912-1992), would play Vance, and his portrayal is considered by critics and lovers of the series to be one of the best. For the much longer 1946-52 run, Jackson Beck (1912-2004, photo at right) would play Vance, and many consider his performance to be the penultimate one, Ferrer notwithstanding. Beck is also known as the announcer for the much beloved The Adventures of Superman radio series (1940-51), and for the voice of Bluto in the series of short animated Popeye features begun in 1933 and shown in theaters across the country.

For the 1945 summer replacement series, native-born Puerto Rican actor (Tony {1947} and Oscar {1950} award winner, both for his portrayal of Cyrano de Bergerac) Jose Ferrer (1912-1992), would play Vance, and his portrayal is considered by critics and lovers of the series to be one of the best. For the much longer 1946-52 run, Jackson Beck (1912-2004, photo at right) would play Vance, and many consider his performance to be the penultimate one, Ferrer notwithstanding. Beck is also known as the announcer for the much beloved The Adventures of Superman radio series (1940-51), and for the voice of Bluto in the series of short animated Popeye features begun in 1933 and shown in theaters across the country.

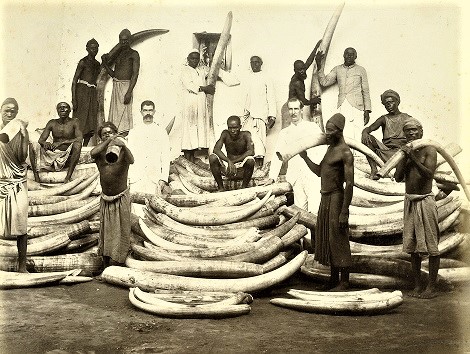

Last week’s John Steele, Adventurer story took us to the jungles of Burma on a wild animal safari, while this week’s tale takes us to Africa in search of elephant ivory. The transport and marketing in ivory of all kinds–in this instance elephant ivory–has been a multi-billion dollar industry for more than a hundred years, whether the money is made legally or illegally. According to Wikipedia:

“In 1942, the African elephant population has [been] estimated to be around 1.3 million in 37 range states, but by 1989, only 600,000 remained. Although many ivory traders repeatedly claimed that the problem was habitat loss, it became glaringly clear that the threat was primarily the international ivory trade. Throughout this decade, around 75,000 African elephants were killed for the ivory trade annually, worth around 1 billion dollars. About 80% of this was estimated to come from illegally killed elephants.”

While the ivory cache at the focus of this episode is stated to have been found and not obtained illegally, we learn there are other reasons for leaving elephant ivory where it has come to rest. Unfortunately, the lure of big money has its price, sometimes deadly, and this ultimate price, born of greed, is the reason Philo Vance finds himself involved in “The Ivory Murder Case.” Oh, and for locked room murder fans, have fun figuring this one out.

Play Time: 26:11

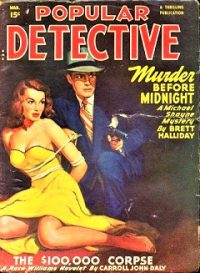

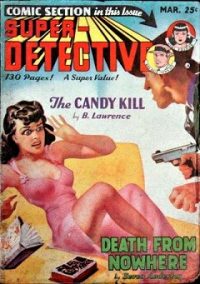

{“The Ivory Murder Case” aired on Wednesday, March 28, 1950. Suffering through school the next day, as soon as the late bell rang the neighborhood gang was off to the nearby newsstand to buy more magazines featuring detective stories like those they enjoyed from the likes of Philo Vance and other detectives on the radio. New Detective (1941-71) was a known and proven quantity that for 27 of its 30 years was a reliable bi-monthly, as it was in March of 1950. Popular Detective (1934-53) was one of the most highly regarded of the detective pulps, often featuring names and stories of the caliber touted on the cover below: Brett Halliday, and Carroll John Daly with another story featuring his popular detective Race Williams. Popular Detective saw 6 issues in 1950. Frankly, I don’t know what to say about Super-Detective (1940-50). While a legitimate detective magazine for adults, it also appears to have run a comic section engineered to attract younger readers—and odd mix, indeed. Somehow it worked, for the magazine ran for a respectable ten years. It managed 6 issues in 1950, though not spaced as regularly as a true bi-monthly.}

[Left: New Detective, Mar. 1950 – Center: Popular Detective, Mar. 1950 – Right: Super Detective, Mar. 1950]

To view the entire list of weekly Old Time Radio episodes at Tangent Online, click here.