Philo Vance (1943-45, 1945, 1946-52) aired “The Deathless Murder Case” on October 25, 1949. The number of total episodes is unknown due to the lack of information on the 1943-45 run, though a good estimate combining the other two runs comes close to 120, though numbers vary. This is but the sixth episode of this well received program we have presented since 2018, the last two appearing in September of 2020 and May of this year (2021). For newcomers and for those needing to refresh their memories, we reprise (with minor variation) the initial background information.

Philo Vance (1943-45, 1945, 1946-52) aired “The Deathless Murder Case” on October 25, 1949. The number of total episodes is unknown due to the lack of information on the 1943-45 run, though a good estimate combining the other two runs comes close to 120, though numbers vary. This is but the sixth episode of this well received program we have presented since 2018, the last two appearing in September of 2020 and May of this year (2021). For newcomers and for those needing to refresh their memories, we reprise (with minor variation) the initial background information.

The character of detective Philo Vance was the brainchild of S. S. Van Dine (pseudonym of Willard Huntington Wright, 1888-1939, photo top right). Wright would pen 12 Philo Vance novels between 1926 and 1939, the first of which was The Benson Murder Case (1926) and the last being The Winter Murder Case which he finished shortly before his death in April of 1939. Vance was very much in the mold of the “gentleman detective” or what would come to be known as the “soft-boiled” variety of detective. He has much in common with Sherlock Holmes and Nero Wolfe in that he was in possession of a giant intellect, though his arrogance and aloofness surpassed that of the former detectives and put many off. As Wright himself wrote of his character (via Van Dine) in The Benson Murder Case: “Vance was what many would call a dilettante, but the designation does him an injustice. He was a man of unusual culture and brilliance. An aristocrat by birth and instinct, he held himself severely aloof from the common world of men. In his manner there was an indefinable contempt for inferiority of all kinds. The great majority of those with whom he came in contact regarded him as a snob. Yet there was in his condescension and disdain no trace of spuriousness. His snobbishness was intellectual as well as social. He detested stupidity even more, I believe, than he did vulgarity or bad taste. I have heard him on several occasions quote Fouché’s famous line: C’est plus qu’un crime; c’est une faute. And he meant it literally.

“Vance was frankly a cynic, but he was rarely bitter; his was a flippant, Juvenalian cynicism. Perhaps he may best be described as a bored and supercilious, but highly conscious and penetrating, spectator of life. He was keenly interested in all human reactions; but it was the interest of the scientist, not the humanitarian.

“Vance’s knowledge of psychology was indeed uncanny. He was gifted with an instinctively accurate judgement of people, and his study and reading had coordinated and rationalized this gift to an amazing extent. He was well grounded in the academic principles of psychology, and all his courses at college had either centered about this subject or been subordinated to it…

“He had reconnoitered the whole field of cultural endeavor. He had courses in the history of religions, the Greek classics, biology, civics, and political economy, philosophy, anthropology, literature, theoretical, and experimental psychology, and ancient and modern languages. But it was, I think, his courses under Münsterberg and William James that interested him the most.”

Unfortunately (or fortunately as is your preference), the radio and film portrayals of Vance toned down his aloof disdain for the common man and made him more likable for audiences. Speaking of the films, there were a dozen adapted from 1929 through 1940. There were a trio of later films made in 1947 but they had nothing to do with the novels and little relationship to the Vance character. Of the first five films (two in 1929, two in 1930–-one being The Benson Murder Case, and the fifth in 1933) William Powell starred in four, while future Sherlock Holmes film star of the 1940s, Basil Rathbone, starred in the fourth (The Bishop Murder Case, 1930). The final Powell role as Vance came with 1933’s The Kennel Murder Case. Such was Powell’s popularity and connection with the movie-going audience that in 1934, barely a year later, he would co-star with Myrna Loy in the first of the classic films adapted from Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man detective novels and stories.

Unfortunately (or fortunately as is your preference), the radio and film portrayals of Vance toned down his aloof disdain for the common man and made him more likable for audiences. Speaking of the films, there were a dozen adapted from 1929 through 1940. There were a trio of later films made in 1947 but they had nothing to do with the novels and little relationship to the Vance character. Of the first five films (two in 1929, two in 1930–-one being The Benson Murder Case, and the fifth in 1933) William Powell starred in four, while future Sherlock Holmes film star of the 1940s, Basil Rathbone, starred in the fourth (The Bishop Murder Case, 1930). The final Powell role as Vance came with 1933’s The Kennel Murder Case. Such was Powell’s popularity and connection with the movie-going audience that in 1934, barely a year later, he would co-star with Myrna Loy in the first of the classic films adapted from Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man detective novels and stories.

For the 1945 summer replacement series, native-born Puerto Rican actor (Tony {1947} and Oscar {1950} award winner, both for his portrayal of Cyrano de Bergerac) Jose Ferrer (1912-1992), would play Vance, and his portrayal is considered by critics and lovers of the series to be one of the best. For the much longer 1946-52 run, Jackson Beck (1912-2004, photo at right) would play Vance, and many consider his performance to be the penultimate one, Ferrer notwithstanding. Beck is also known as the announcer for the much beloved The Adventures of Superman radio series (1940-51), and for the voice of Bluto in the series of short animated Popeye features begun in 1933 and shown in theaters across the country.

For the 1945 summer replacement series, native-born Puerto Rican actor (Tony {1947} and Oscar {1950} award winner, both for his portrayal of Cyrano de Bergerac) Jose Ferrer (1912-1992), would play Vance, and his portrayal is considered by critics and lovers of the series to be one of the best. For the much longer 1946-52 run, Jackson Beck (1912-2004, photo at right) would play Vance, and many consider his performance to be the penultimate one, Ferrer notwithstanding. Beck is also known as the announcer for the much beloved The Adventures of Superman radio series (1940-51), and for the voice of Bluto in the series of short animated Popeye features begun in 1933 and shown in theaters across the country.

“The Deathless Murder Case” concerns itself with a theme usually associated with science fiction—the search for immortality, the dream of living forever. In this story, however, a man who claims to be 400 years old tries to turn a profit on his centuries-old longevity by offering to extend the lifespan of rich women for a mere $100,000. One of the interested women is a friend of Philo Vance’s who wisely decides to pay him a visit and solicit his investigative expertise to vet the man making his extraordinary claim, and his ability to pass the secret on to others. After speaking to this enigmatic man at some length, Vance finds his story a tough nut to crack, for his seemingly intimate knowledge of various times and people from the past appears genuine; he knows details no one could know without living in the time periods he claims to have lived through. Can his claim of finding the secret to open-ended longevity be true? Reason says no, of course not, but what facts are available point to the possibility of the impossible being true. Full of skepticism and determined to get to the bottom of this mystery, Philo Vance goes to work on the case, a true test of his intellectual acumen, as he endeavors to solve “The Deathless Murder Case” before his friend forks over $100,000 for the ostensible Secret of the Ages, Ponce de Leon’s legendary Fountain of Youth, if you will. History buffs have fun. And did I mention there is a murder involved?

Play Time: 27:28

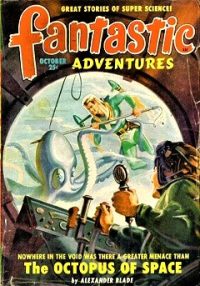

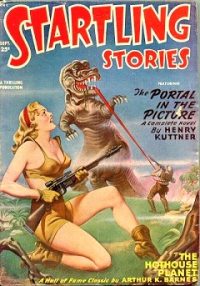

{After listening to “The Deathless Murder Case” on a Tuesday evening in late October, the neighborhood gang found themselves at the nearby newsstand on their way home from school the next afternoon. While the radio play was a mystery, the science-fictional element persuaded them to look for SF magazines rather than detective magazines this particular visit. Astounding SF (1930-present, now Analog) was not to be denied even though it sported no author names or story titles on the cover. Scanning the table of contents later, however, would reveal stories by Poul Anderson, L. Ron Hubbard, Kris Neville, and Katherine MacLean among others. Not a shabby lineup. Astounding was a monthly in 1949. fantastic Adventures (1931-53) was founded by legendary genre publisher/editor Raymond A. Palmer (RAP) as a companion to his other edited magazine and SF’s flagship publication Amazing Stories. Its initial mandate was to publish stories lighter in tone than its older sister magazine, but according to a reliable source by the late 1940s it was running much the same kind of material as Amazing. fantastic Adventures was also a monthly in 1949. Startling Stories (1939-55) was one of the most beloved of the early SF pulps, running colorful adventure fare by some of the most famous authors in the field. Imagination ruled over scientific rigor in its stories and readers young and old cared not a twit. Many of its issues are now considered collector items at SF conventions. It was a bi-monthly in 1949.}

[Left: Astounding SF, Oct. 1949 – Center: fantastic Adventures, Oct. 1949 – Right: Startling Stories, Sept. 1949]

To view the entire list of weekly Old Time Radio episodes at Tangent Online, click here.