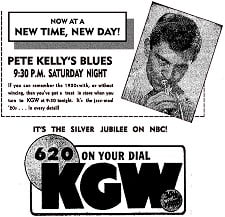

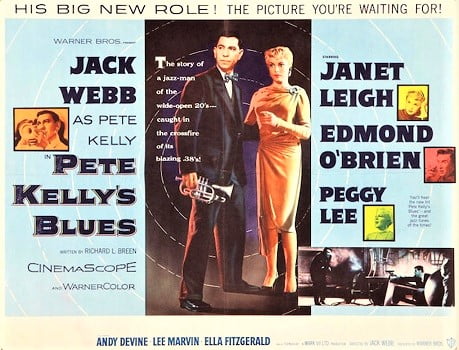

Pete Kelly’s Blues (July 4-September 19, 1951) aired “Little Jake” as the 4th of its 13 shows on July 25, 1951. It was a summer replacement show, and though not able to continue on radio beyond its replacement gig it did manage a much admired 1955 film starring Jack Webb (1920-1982), Janet Leigh, and Edmond O’Brien. (Famed film director Martin Scorsese named it one of his top 15 gangster films of all time.) And in 1959 Pete Kelly’s Blues came to television for one 13 episode season, to make it a triple media production. Jack Webb would star in the radio and film incarnations but worked behind the camera on the TV show as executive producer of all 13 episodes, and writer and director of one episode.

Pete Kelly’s Blues (July 4-September 19, 1951) aired “Little Jake” as the 4th of its 13 shows on July 25, 1951. It was a summer replacement show, and though not able to continue on radio beyond its replacement gig it did manage a much admired 1955 film starring Jack Webb (1920-1982), Janet Leigh, and Edmond O’Brien. (Famed film director Martin Scorsese named it one of his top 15 gangster films of all time.) And in 1959 Pete Kelly’s Blues came to television for one 13 episode season, to make it a triple media production. Jack Webb would star in the radio and film incarnations but worked behind the camera on the TV show as executive producer of all 13 episodes, and writer and director of one episode.

As to the radio show, Digital Deli Too sets the stage with its description of the show: “Pete Kelly’s Blues takes place in the jazz era in the early twenties. The main character, as portrayed by Webb, is a young cornet player. The action occurs in Kansas City, circa 1922, and the trademarks of that time–the gangsters, flappers, prohibition agents and jazz music–will figure in the plot.

“At least two full musical numbers will be played during each program of the show. Webb, who is an avid jazz fan in private life, has collected all the musicians who will play on his show.”

Jack Webb, as noted above, was a diehard jazz enthusiast, his collection of jazz recordings totaling some 6,000, and his 1920 cornet (on which he would practice for hours at a time as a youth) was one of his prize possessions. Again, according to Digital Deli Too: “Jack Webb was a life-long perfectionist. His Pete Kelly’s Blues project was no exception. Webb obtained the talents of the finest jazz performers available to assemble his “Big 7” Jazz Band for the series. Brothers Ray and Moe Schneider joined famed cornetist Dick Cathcart, Nick Fatool, Matty Matlock and Bill Newman to form the core of the group. Their performances during each of the thirteen episodes of the radio program were as eagerly anticipated as the drama itself.”

Jack Webb, as noted above, was a diehard jazz enthusiast, his collection of jazz recordings totaling some 6,000, and his 1920 cornet (on which he would practice for hours at a time as a youth) was one of his prize possessions. Again, according to Digital Deli Too: “Jack Webb was a life-long perfectionist. His Pete Kelly’s Blues project was no exception. Webb obtained the talents of the finest jazz performers available to assemble his “Big 7” Jazz Band for the series. Brothers Ray and Moe Schneider joined famed cornetist Dick Cathcart, Nick Fatool, Matty Matlock and Bill Newman to form the core of the group. Their performances during each of the thirteen episodes of the radio program were as eagerly anticipated as the drama itself.”

Pete Kelly’s Blues is a product of its time and Jack Webb captures it well. Kansas City, MO during the 1920s was a hotbed of the jazz and blues scene, organized crime, and crooked politicians. Juke joints, drugs, and other aspects of the fast and loose high life were the order of the day. While the speakeasy in which the show takes place is given as 417 Cherry St. (a north-south street 6 blocks east of Main St.), today that location is a low rent, older looking section of KC close to the east-west running Missouri river just a scant few blocks to its north (an ideal place for dumping dead bodies back in the 1920s one might imagine). For at least some period of time until recently the entire 400 block of Cherry St. was an empty lot. Today a long, single story brick building whose solid rear wall faces Cherry St. marks the otherwise nondescript location. And to further emphasize the atmosphere of Kansas City that Webb captured so well in “Pete Kelly’s Blues,” know that the 1920s was ruled by a corrupt politician by the name of Tom Pendergast, a name well known to those of us long-time Kansas City natives. From the pendergastkc.com web page: “For nearly a decade and a half between 1925 and 1939, political boss Thomas J. Pendergast (or simply “Boss Tom”), an unelected dealmaker and leader of the local “goat” Democratic faction, consolidated control of Kansas City’s machine politics and ruled its government and criminal underworld with impunity. Prior to those years, Boss Tom and his elder brother, James F. Pendergast, who died in 1911, had long vied for control with other aspiring bosses. Chief among the rivals was Joseph B. Shannon, leader of the “rabbit” faction of the Democratic party. Boss Tom, the namesake of this website, overshadowed Kansas City and exerted influence on most of the best and worst aspects of its history throughout his reign. As reform efforts swept in and the Pendergast Years faded away, so did much of the city’s Jazz Age identity.”

As an aside, future President of the United States Harry S. Truman’s political career began under the Pendergast regime, where he was carefully groomed and climbed his way up through the ranks with Pendergast’s blessing and support. From Truman’s wikipedia page:

“With the help of the Kansas City Democratic machine led by Tom Pendergast, Truman was elected in 1922 as County Court judge of Jackson County’s eastern district—Jackson County’s three-judge court included judges from the western district (Kansas City), the eastern district (the county outside Kansas City), and a presiding judge elected countywide. This was an administrative rather than judicial court, similar to county commissioners in many other jurisdictions. Truman lost his 1924 reelection campaign in a Republican wave led by President Calvin Coolidge’s landslide election to a full term. Two years selling automobile club memberships convinced him that a public service career was safer for a family man approaching middle age, and he planned a run for presiding judge in 1926.

“In 1926, Truman was elected to the judgeship with the support of the Pendergast machine, and he was re-elected in 1930.”

Such was the colorful social and political atmosphere Jack Webb painted so well in Pete Kelly’s Blues. In this episode (one of the remaining 6 episodes still in circulation and the one with the best audio from its original recording), Pete Kelly is visited at the club by some of the underworld cronies he had inevitably brushed shoulders with from time to time but tried to distance himself from. He is asked to do something at a certain time for them, or else. Agreeing reluctantly, things go terribly wrong from there on and more than one person is killed. “Little Jake” is a perfect example of the dark, unforgiving, noir gangster scene Pete Kelly’s Blues became known for, and which translated so well in the later classic 1955 film.

Jack Webb was a busy man in the 1940s and 50s as a producer and writer, above and beyond the several shows in which he starred. A few of his more notable shows–in the same hardboiled detective vein–were Jeff Regan, Investigator (1948-50), Pete Kelly’s Blues (July-September 1951, set in Kansas City and with a nod to Webb’s love of jazz), and of course Dragnet (1949-57). Note that each of these shows in one way or another and for a shorter or longer period of time, overlapped with another of Webb’s shows. Following his earlier efforts which took aim at the “Chandleresque” mode of dialog, with Dragnet Webb played it straight all the way down the line. His no nonsense, clipped dialogue and matter-of-fact presentation became iconic and translated into the tv version of the show quite well. Webb was so dedicated to law and order and the police ethic that to make Dragnet as accurate as possible he sought LA police advice and consulted with them regularly, studying their methods first hand, befriending many of them through the years of the tv show. When Webb died of a heart attack at the age of 62 on December 23, 1982, Los Angeles Police Chief Daryl Gates retired badge number 714, the number worn by Webb’s character Joe Friday on the tv show. Webb has two stars on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame, one for his TV work and one for Radio.

Jack Webb was a busy man in the 1940s and 50s as a producer and writer, above and beyond the several shows in which he starred. A few of his more notable shows–in the same hardboiled detective vein–were Jeff Regan, Investigator (1948-50), Pete Kelly’s Blues (July-September 1951, set in Kansas City and with a nod to Webb’s love of jazz), and of course Dragnet (1949-57). Note that each of these shows in one way or another and for a shorter or longer period of time, overlapped with another of Webb’s shows. Following his earlier efforts which took aim at the “Chandleresque” mode of dialog, with Dragnet Webb played it straight all the way down the line. His no nonsense, clipped dialogue and matter-of-fact presentation became iconic and translated into the tv version of the show quite well. Webb was so dedicated to law and order and the police ethic that to make Dragnet as accurate as possible he sought LA police advice and consulted with them regularly, studying their methods first hand, befriending many of them through the years of the tv show. When Webb died of a heart attack at the age of 62 on December 23, 1982, Los Angeles Police Chief Daryl Gates retired badge number 714, the number worn by Webb’s character Joe Friday on the tv show. Webb has two stars on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame, one for his TV work and one for Radio.

Play Time: 29:35

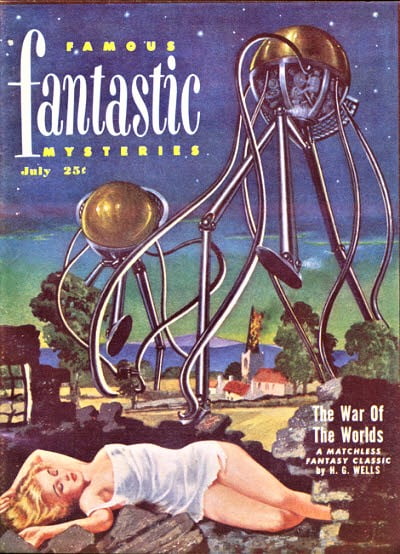

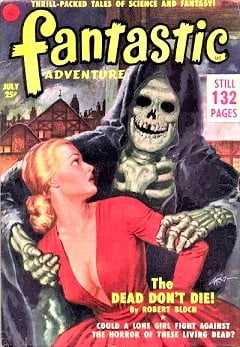

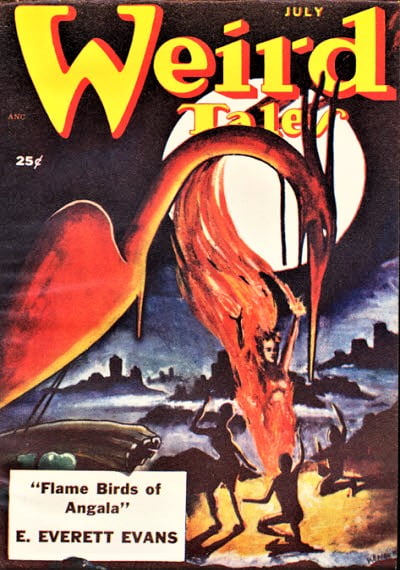

{July of 1951 found the neighorhood gang in fine fettle as they played baseball from dawn till dusk in the local park on a makeshift ball field, with nary a break for lunch and a bottle of pop until they were back at it again. Dusty and tired, they made their way to the nearby newsstand on the way home for dinner and picked up a few more issues of their favorite pulp magazines. Famous fantastic Mysteries (1939-53) ran reprints of classic sf/f stories, so any issue featuring Wells’s classic The War of the Worlds was a sure bet. It was a bi-monthly in 1951. fantastic Adventures (1939-53) ran fast-paced, imagination-grabbing stories of all stripes, and a cover story promoting a Robert Bloch tale only added to its sales appeal. It was a monthly in 1951. Weird Tales (1923-54), rightly dubbed “the unique magazine” was nearing the end of its multi-decade run but still held a dedicated and devoted audience in 1951 with stories as exotic, dark, and bizarre as ever. It was a bi-monthly in 1951.}

[Left: Famous fantastic Mysteries, July 1951 – Center: fantastic Adventures, July 1951 – Right: Weird Tales, July 1951]

To view the entire list of weekly Old Time Radio episodes at Tangent Online, click here.