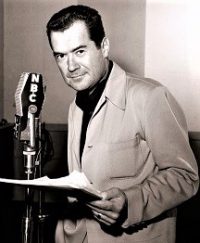

Nightbeat (1950-52) aired “Marvelous Machine” on June 5, 1952 as its 97th episode out of approximately 118 (depending on how one counts). Some 80 episodes are estimated to remain in circulation. This radio noir “detective” show featured film–and later TV–star Frank Lovejoy (1912-1962) as Randy Stone, the nightbeat reporter for the fictional Chicago Star newspaper.

Nightbeat (1950-52) aired “Marvelous Machine” on June 5, 1952 as its 97th episode out of approximately 118 (depending on how one counts). Some 80 episodes are estimated to remain in circulation. This radio noir “detective” show featured film–and later TV–star Frank Lovejoy (1912-1962) as Randy Stone, the nightbeat reporter for the fictional Chicago Star newspaper.

This is only the fifth episode of Night Beat we have showcased, the first being “The Devil’s Bible” from July of 2013, the second “Mentallo, the Mental Marvel” from May of 2019, the third being “The Slasher” from December of 2019, and the fourth being “Lost Souls” from February of 2020, a full year ago. So a bit of background on the show is in order for newcomers. While well received, it ran for a modest two years before being cancelled, but not from any fault of its own. It had two factors going against it, both with origins at NBC. The time for a new radio show, and for a network to pour money into it, wasn’t the best. The early 1950s was becoming a growth spurt for the relatively new medium of television, and advertisers realizing its much larger potential audience were diverting their ad dollars away from radio and into this promising new market. Secondly, and for whatever reason, NBC around this time had a reputation for not supporting many of its shows with in-house advertising around the country, or allowing them the benefit of stable time slots so audiences could plan on listening to their favorite shows at a regular time. Both of these factors had a role in Night Beat‘s short life span. NBC would move it from one day of the week to another and at a different nightly time slot, without notice or fanfare, making it difficult for its audience to follow. Thus, while the show was a success, it was in spite of NBC, not because of anything its parent network did to support it.

As noted above, Frank Lovejoy portrayed Randy Stone, the night beat reporter for the fictional newspaper, the Chicago Star. He wasn’t the show’s first choice, however. Noted film actor Edmond O’Brien played Stone in an audition episode, but the censorship watchdogs that had for a long time been active in radio felt O’Brien’s hardcore, gritty characterization of Stone to be too stark for younger listeners, so decreed that Night Beat would have to air in a later time slot if it was to be given a green light. Rather than moving their new show in the making to a late night venue (with fewer listeners and thus fewer potential ad dollars spent), they would soften the Stone character. Enter Frank Lovejoy, with a voice historians would later place in the top ten of the most distinctive voices in radio. Lovejoy also brought his own sense of down to earth humanity and heartfelt compassion to the role (which he did to all of his radio roles, some 3,000 productions during his radio career), and Night Beat had its winning formula.

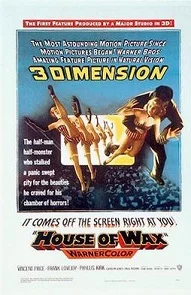

Lovejoy was a well known and respected film actor in the 1940s and 50s, having supporting or major roles in more than two dozen films, a scant few of many worth mentioning being 1949’s In a Lonely Place (starring Humphrey Bogart), and the title role in the classic 1951 noir crime thriller I Was a Communist for the FBI. Lovejoy featured prominently in several world War II and/or Korean War films, the most high profile probably his co-starring role with James Stewart in 1954’s Strategic Air Command. Of interest to SF genre fans is Lovejoy’s role as Lt. Tom Brennan opposite Vincent Price in the 1953 3D horror flick House of Wax (the first color 3D film to be released by a major American studio, and the first in a regular theater setting to offer stereophonic sound).

“Marvelous Machine” could easily be considered a science fiction tale, in that it deals with a bit of future technology, a machine ahead of its time whose script actually explores one of the serious ramifications of its existence. It concerns one Assistant Professor of Electronics Keefer and the “high speed calculator” also called a “mechanical brain” he has been perfecting, how he is involved, if at all, in a murder, and the shady aspects of the horse racing racket. What surprises more than the competent storyline, however, is the unexpected social moralizing at the very end, a philosophical debate that is still very much with us to this very day, perhaps even more relevant now than ever before when machines of all types threaten to replace the human labor force, in a piecemeal fashion, industry job by industry job (and what suitable jobs semi-skilled laborers, now out of work, could find when laid off for whatever reason). It is actually quite a prescient script if you have kept tabs on what has been suggested by the current administration in Washington, D.C. for those it has forced from their high-paying jobs on the Keystone Pipeline. Regardless of which side of this issue your opinion resides, bravo to the writer of this episode for bringing this controversial subject to light. Do give it a listen.

Play Time: 30:00

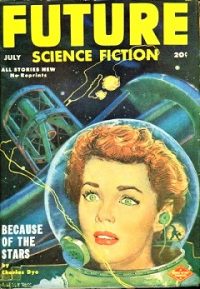

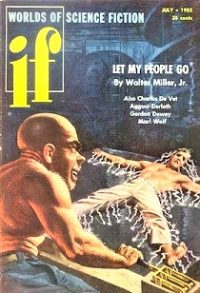

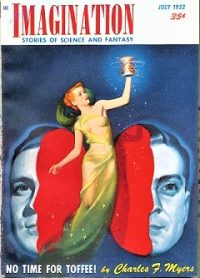

{It was a Thursday when “Marvelous Machine” aired in 1952. School has just let out for summer vacation and the neighborhood gang didn’t waste any time getting to the nearby newsstand the next morning, a Friday and the start to a carefree weekend. Future SF (1950-54) was a relatively new SF magazine and was quickly added to the ever-growing list of genre collectibles. It was a bi-monthly in 1952. Worlds of If (1952-74) was another new title eager young readers easily forked over their nickels, dimes, and quarters to sample, and what they found must have been met with considerable approval, for its publishing run lasted for more than 20 years. Begun as a sister magazine to Galaxy, after a number of editors in the 1950s (including Galaxy‘s editor Horace Gold) Frederik Pohl would assume the editor’s chair at If in 1962 and would go on to win three consecutive Hugo awards for Best Magazine from 1966-68. If was a bi-monthly in 1952. Imagination (1950-58) was yet another of Ray Palmer’s publishing ventures, which he promptly sold after three issues. It published mostly colorful, entertaining adventure fare by the calculated preference of its editor, William Hamling, whose stated philosophy was that “science fiction was never meant to be an educational tour de force.” Looked down on by some critics, the magazine nevertheless ran stories by Robert Sheckley (his first sale), Philip K. Dick, Robert A. Heinlein, and others. It too was a bi-monthly in 1952.}

[Left: Future SF, July 1952 – Center: Worlds of If, July 1952 – Right: Imagination, July 1952]

To view the entire list of weekly Old Time Radio episodes at Tangent Online, click here.