Mr. Keen, Tracer of Lost Persons (1937-1955) aired “The Skull and Crossbones Murder Case” on May 18, 1950. This is only the 3rd episode of Mr. Keen we have offered, the first two coming in January and June of last year, 2024. A reprise of the introductory material from those earlier shows is in order for newcomers, as well as for those familiar with the show who may need a quick reminder of the show’s basic concept.

Mr. Keen, Tracer of Lost Persons (1937-1955) aired “The Skull and Crossbones Murder Case” on May 18, 1950. This is only the 3rd episode of Mr. Keen we have offered, the first two coming in January and June of last year, 2024. A reprise of the introductory material from those earlier shows is in order for newcomers, as well as for those familiar with the show who may need a quick reminder of the show’s basic concept.

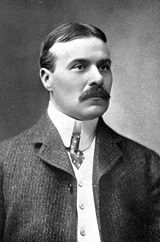

The program was the brainchild of, and produced by the team of Frank and Anne Hummert, who were inspired by the 1906 novel The Tracer of Lost Persons by American author and artist Robert W. Chambers.

Mr. Keen, Tracer of Lost Persons holds the distinction of being the longest running of any detective show on radio, with its 1,690 broadcasts far outstripping its fellow detective shows, including (according to wikipedia): “Nick Carter, Master Detective (726 broadcasts), The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (657) and The Adventures of the Falcon (473).” Unfortunately, out of the almost 1,700 episodes over its 18-year run, fewer than 60 shows have survived.

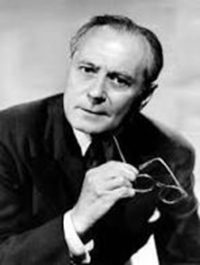

Bennett Kilpack (1883-1962, photo top right) starred as Mr. Keen, who came to be known as “the kindly old investigator,” and Jim Kelly would play the role of Keen’s Irish partner Mike Clancy. From 1937-1942 the NBC network aired the show three times a week in short 15-minute episodes, and true to the show’s name involved Mr. Keen tracking down people who had disappeared for one reason or another and had left families, homes, or jobs behind. In November of 1943 (and now with the CBS radio network since 1942) the format changed to full half hour shows, and Mr. Keen’s skills were expanded to include those of a full-fledged investigator, one who used his intellect and cunning not only to find missing persons, but to bring murderers to justice as well. Kilpack played Keen for nearly 1,300 episodes for 13 years, at which time he made his final appearance on October 26, 1950. Following his “retirement” from the show (its 1,314th broadcast), Mr. Keen would be played by Arthur Hughes and Phil Clarke, with the program’s final episode airing on April 19, 1955. While the show absorbed and survived criticism in some quarters for being written to a very broad-based (i.e., lowest common denominator) audience, it enthralled such a large swath of the listening public on a regular basis, providing it with much needed relief from the day to day grind, that it lasted for nearly 20 years, even unto the dawn of the television age.

Before teasing this week’s episode, I’d like to give a nod to the author of the book who gave inspiration to the Hummett’s for Mr. Keen, Tracer of Lost Persons. Robert W. Chambers (1865-1933) was a prolific author who wrote dozens of novels, short stories, more than a handful of children’s books, and whose stories of his own work were collected in several volumes, with a number of his detective and/or supernatural tales reprinted in numerous anthologies. Chambers’ most famous work for fans of the fantasy genre is perhaps his 1895 collection of 9 stories, The King in Yellow. His wikipedia page provides the following paragraph of this singular work: “The book contains nine short stories and a sequence of poems; while the first stories belong to the genres of supernatural horror and weird fiction, The King in Yellow progressively transitions towards a more light-hearted tone, ending with romantic stories devoid of horror or supernatural elements. The horror stories are highly esteemed, and it has been described by critics such as E. F. Bleiler and T. E. D. Klein as a classic in the field of the supernatural. Lin Carter called it ‘an absolute masterpiece, probably the single greatest book of weird fantasy written in this country between the death of Poe and the rise of Lovecraft,’ and it was an influence on Lovecraft himself.”

Before teasing this week’s episode, I’d like to give a nod to the author of the book who gave inspiration to the Hummett’s for Mr. Keen, Tracer of Lost Persons. Robert W. Chambers (1865-1933) was a prolific author who wrote dozens of novels, short stories, more than a handful of children’s books, and whose stories of his own work were collected in several volumes, with a number of his detective and/or supernatural tales reprinted in numerous anthologies. Chambers’ most famous work for fans of the fantasy genre is perhaps his 1895 collection of 9 stories, The King in Yellow. His wikipedia page provides the following paragraph of this singular work: “The book contains nine short stories and a sequence of poems; while the first stories belong to the genres of supernatural horror and weird fiction, The King in Yellow progressively transitions towards a more light-hearted tone, ending with romantic stories devoid of horror or supernatural elements. The horror stories are highly esteemed, and it has been described by critics such as E. F. Bleiler and T. E. D. Klein as a classic in the field of the supernatural. Lin Carter called it ‘an absolute masterpiece, probably the single greatest book of weird fantasy written in this country between the death of Poe and the rise of Lovecraft,’ and it was an influence on Lovecraft himself.”

Last week’s old time radio offering, a classic spy thriller adapted several times for radio and the silver screen, was rather convoluted, so this week I offer a different sort of story, a relatively quotidian who-done-it to test your ratiocinative skills. The opening scene finds a wealthy gentleman of years and his younger wife finishing dinner, a quiet affair where their after-dinner coffee is about to be served by their housemaid. Nothing seems amiss until the husband chokes, keels over and dies after tasting his coffee. Has he died of natural causes related to his age? Or was there something in his coffee that initiated his abrupt demise, poison being an understandable cause? If the latter, Mr. Keen must pursue the logical suspects, a small cast of characters each with a motive for murder, some more likely than others. It is Mr. Keen’s job to wade through the facts, few as they may be, and then square them with what he learns from his interviews with the suspects. Who had the most to gain either monetarily or from some other undisclosed motive? What may appear as obvious often is not in a seemingly straightforward murder case such as this appears to be, so Mr. Keen must rely on his intuitive prowess to focus his attention in the proper direction if he is to solve “The Skull and Crossbones Murder Case.”

(The linked CD at top includes this episode and 19 others. Please note that it is periodically sold out.)

Play Time: 29:40

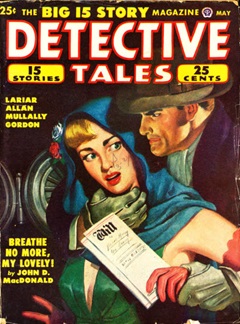

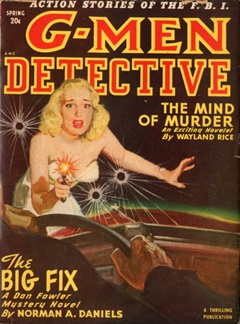

{Airing on a Thursday evening in the middle of May, 1950, the neighborhood gang knew that after school the next afternoon a visit to the nearby newsstand was in order. Being Friday, they knew without any formal declaration among them that their only goal was to bring home more tales of murder and other assorted skullduggery to carry them through the weekend. They were in luck. Detective Tales (1935-53) had the second highest circulation among Popular Publications’ detective pulps, and with John D. MacDonald’s name on the cover a sure sale was in order. Detective Tales was a monthly in 1950. Dime Detective (1931-53) was also one of Popular Publications’ detective pulps and had the distinction of being its most popular. It also enjoyed the added luxury of having John D. MacDonald among its stable of writers, so his name on the cover of any issue was a plus for its eager audience. Dime Detective was, like its slightly younger companion detective pulp, a monthly in 1950. G-Men Detective (1935-53) took advantage of the popularity of federal agent adventures (both written and filmed gangster exploits) when it debuted in 1935, and was an instant success. But by 1940 the interest in federal agent tales flagged and the magazine changed its name from G-Men to G-Men Detective and slowed to a 6-issue per year bi-monthly schedule. In 1950, nearing the end of its successful run, it was a quarterly.}

[Left:Detective Tales, 5/50 – Center: Dime Detective, 5/50 – Right: G-Men Detective, Spring/50]

To view the entire list of weekly Old Time Radio episodes at Tangent Online, click here.