Lights Out! (1934-1947) aired “Knock at the Door”” on Tuesday, December 15, 1942 as the 11th of the 52 episodes of the 1942-43 season. This is our 20th Lights Out! episode since June of 2009 but only the 3rd since September of 2016, the last coming in January of 2022. Since that last episode, where much background material was put forth about the series’ history, as well as behind the scenes anecdotes concerning the program’s wild popularity, we felt it was time to repeat the fascinating back story for newcomers, with the usual follow up teaser about the current episode.

Lights Out! (1934-1947) aired “Knock at the Door”” on Tuesday, December 15, 1942 as the 11th of the 52 episodes of the 1942-43 season. This is our 20th Lights Out! episode since June of 2009 but only the 3rd since September of 2016, the last coming in January of 2022. Since that last episode, where much background material was put forth about the series’ history, as well as behind the scenes anecdotes concerning the program’s wild popularity, we felt it was time to repeat the fascinating back story for newcomers, with the usual follow up teaser about the current episode.

The original iteration of Lights Out! ran from 1934-39, producing some 274 original scripts (of which only around 140 are believed to still exist), though it was revived for short periods of time–using many recycled or updated scripts from the 1930s–off and on until 1947. The show was created by Willis (aka Wyllis) Cooper who, the story goes, after a hard day’s work and tired of listening to the same old late night radio dance band programs, decided to write his own supernatural and horror stories for his own amusement (though he frightened himself so much that sometimes he couldn’t finish his own stories until the next morning). A fan of mystery and horror stories (he was especially frightened of ghost stories), he eventually convinced a local Chicago radio station (an NBC affiliate) to produce Lights Out! using his own material, and which would air at midnight, far past the bedtime for impressionable children. After the show had run for maybe a year it was announced without fanfare that the show was at an end, whereupon the radio station was deluged with irate fans from around the country demanding the show continue. Bowing to the pressure, the program was quickly revived and within three weeks Lights Out! once again was scaring the pants off of its ever-growing cult-like audience. It became so popular that fan clubs sprang up all over the country and numbered around 600 by mid-1936. Small to large groups of fans would gather at a host’s house and play cards or listen to the radio for hours ahead of the show’s midnight airing, for it was the early 1930s episodes that made it one of the most talked about horror shows of all time, notably for its gruesome sound effects and grisly scenes of murder (dismembered bodies, bodies dissolved to bones in acid baths, etc.).

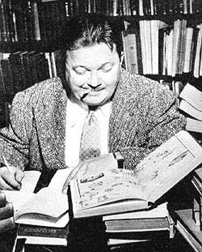

Even the cast and crew became so involved in the plays they were reading or producing that as the programs began all lights in the studio were turned off, except for the pin lights needed for the reading of the scripts or those needed by the equipment technicians. Cooper (1899-1955, photo at left) was at the helm from the show’s inception in 1934 through mid-1936, at which point he would venture to Hollywood to work on films (most notably the script for the mediocre 1939 Son of Frankenstein). From 1936 on, the wunderkind Arch Oboler (1909-1987, photo at right) would, with rare exceptions, write all of the show’s scripts through the 1943 season, sometimes borrowing or adapting stories from his other radio shows, a few with a much more social or political message (Oboler was a staunch anti-Nazi)–-though retaining the much-loved supernatural or horror element. Following the 1943 season, others would script the various episodes, including Wyllis Cooper who would pen a handful or two over time. Oboler would remain connected to the show as either producer, host, or both; however, the money he was paid for his Lights Out! efforts would help finance his own private radio plays for which he would come to be highly regarded, especially during the war years amid the fervor of anti-Nazi sentiment in the United States.

Even the cast and crew became so involved in the plays they were reading or producing that as the programs began all lights in the studio were turned off, except for the pin lights needed for the reading of the scripts or those needed by the equipment technicians. Cooper (1899-1955, photo at left) was at the helm from the show’s inception in 1934 through mid-1936, at which point he would venture to Hollywood to work on films (most notably the script for the mediocre 1939 Son of Frankenstein). From 1936 on, the wunderkind Arch Oboler (1909-1987, photo at right) would, with rare exceptions, write all of the show’s scripts through the 1943 season, sometimes borrowing or adapting stories from his other radio shows, a few with a much more social or political message (Oboler was a staunch anti-Nazi)–-though retaining the much-loved supernatural or horror element. Following the 1943 season, others would script the various episodes, including Wyllis Cooper who would pen a handful or two over time. Oboler would remain connected to the show as either producer, host, or both; however, the money he was paid for his Lights Out! efforts would help finance his own private radio plays for which he would come to be highly regarded, especially during the war years amid the fervor of anti-Nazi sentiment in the United States.

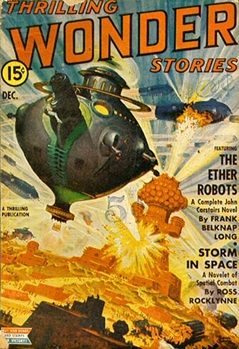

“Knock at the Door” reminds me of the famous science fiction story (the shortest on record) published in the December 1948 issue of Thrilling Wonder Stories. Written by the late master of the short-short story Fredric Brown (1906-72), his story “Knock” is complete with the following two sentences: “The last man on Earth sat alone in a room. There was a knock on the door …”. In Brown’s story we never learn who or what knocked on the door because it was beside the point of the story. However, in “Knock at the Door” there is most certainly a need to know about the knock at the door, the who or what and why of it. We certainly find out down the road and after characters and a situation or two have been set in place, but what happens up to that pivotal point is both creepy in several sometimes unpleasant ways, and the story line as such doesn’t seem to be as important as at least one tall, quirky character who speaks like a slow-witted mama’s boy who is unintentionally humorous as he mouths the lines the writer has given him. This dim-wit is also somewhat of a pervert, so if you can somehow imagine a large, thick-tongued, mama’s boy with a scoche of the pervert in him then you won’t care if there’s not much of a story line, but might enjoy the weirdo crazy quilt of a story that somehow fascinates like rubber-necking a bad accident on the highway. And like a grisly highway accident, there just might be a corpse or two here as well, just to make things interesting. Then there’s that “Knock at the Door” we’ve all been waiting for, which is probably the most commonplace occurrence of anything in this otherwise very odd peek into what usually happens only behind closed doors. Or something like that.

(The CD linked above contains this episode and 19 others on 10 CDs, all restored and remastered.)

Play Time: 27:39

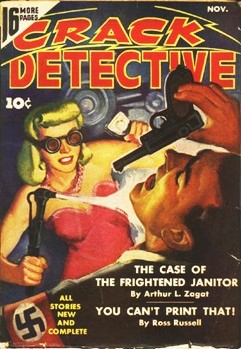

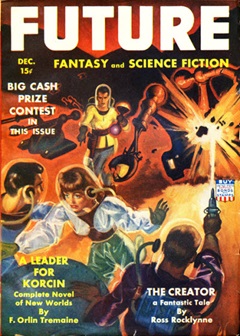

{Airing on a Tuesday evening a scant 10 days before Christmas in 1942, the neighborhood gang enjoyed a little early holiday present by stopping at the nearby newsstand after school the next day, in search of excitement like that of the Lights Out! episode of the night before. They discovered that elusive excitement in several ways in the pulp magazines they gifted themselves with on a cold December afternoon. Crack Detective (1938-57) was only one of eight titles this magazine would adopt during its almost 20-year run. One of the authors who made the cover of the issue below was Arthur L. Zagat, a name early science fiction fans would recognize as a favorite pulpster from his stories in the earliest SF magazines. Before its name would change again, Crack Detective would sport the title from May 1942 through September 1943 and was a bi-monthly during this time. Future combined with Science Fiction (1941-43) like Crack Detective, would undergo several name changes, among them Future Fiction (1939-41) and Future Combined with Science Fiction Stories (1950-54). During its brief 1941-43 tenure it would change its name twice: once to the title you see below as Future, Fantasy and Science Fiction (Oct. 1942-Feb. 1943), and finally to Science Fiction for its last 2 issues (April & July 1943). Save for those two final issues in 1943, regardless of any other title changes, the magazine was a bi-monthly. Thrilling Wonder Stories (1936-55) was a much beloved pulp featuring action-packed stories replete with exotic locales and colorful backgrounds from which the stories played themselves out. Scientific accuracy wasn’t exactly at the top of the list when it came to the nuts and bolts of the stories, but youngsters never seemed to mind if they found anything scientifically amiss. Instead, many a popular (and future famous) author would enthrall the magazine’s eager readers at every turn. There was never a dull moment in the pages of TWS, and its allegiance to unfettered imagination couldn’t be beat. It was a bi-monthly in 1942.}

[Left: Crack Detective, 11/42 – Center: Future w/F&SF, 12/42 – Right: TWS, 12/42]

To view the entire list of weekly Old Time Radio episodes at Tangent Online, click here.