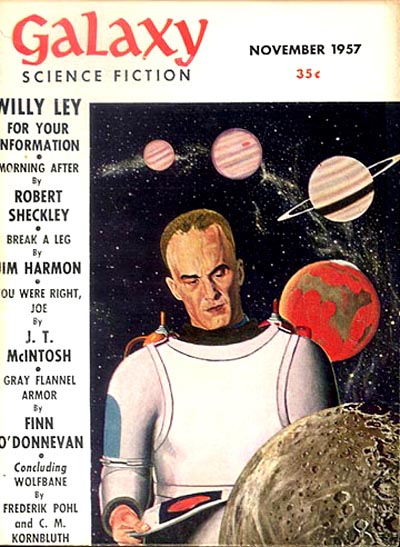

Robert Sheckley (1928-2005) is regarded as one of the finest short story writers in SF history, his voluminous short work being lauded by J.G. Ballard, Harlan Ellison, Alan Dean Foster, and many others. Hugo and Nebula nominated for his sparkling, clever, sometimes absurdist visions, he was named SFWA Author Emeritus at the 2001 Nebula Awards in Los Angeles, where I was fortunate enough to meet him for the first and last time. “Gray Flannel Armor” is Sheckley’s third X Minus One appearance here. It appeared in the November 1957 issue of Galaxy, under the pen name of Finn O’Donnevan (note that the cover has another Sheckley story, “Morning After,” under his own name, along with the conclusion of Fred Pohl and Cyril Kornbluth’s novel Wolfbane).

Robert Sheckley (1928-2005) is regarded as one of the finest short story writers in SF history, his voluminous short work being lauded by J.G. Ballard, Harlan Ellison, Alan Dean Foster, and many others. Hugo and Nebula nominated for his sparkling, clever, sometimes absurdist visions, he was named SFWA Author Emeritus at the 2001 Nebula Awards in Los Angeles, where I was fortunate enough to meet him for the first and last time. “Gray Flannel Armor” is Sheckley’s third X Minus One appearance here. It appeared in the November 1957 issue of Galaxy, under the pen name of Finn O’Donnevan (note that the cover has another Sheckley story, “Morning After,” under his own name, along with the conclusion of Fred Pohl and Cyril Kornbluth’s novel Wolfbane).

A word of warning, or explanation if you will. Sometimes a story gives rise to a lengthier introduction via its historical context than the norm. Such is the case here, so please bear with me.

“Gray Flannel Armor” is a deceptively simple story, for it deals with lonely people searching for someone to love. In this prescient story however, Sheckley combines cutting edge technology with the human element and a (relatively) early incarnation of the “dating” service. The cutting edge technology? The transistor.

The transistor is very old technology now, but when Sheckley wrote “Gray Flannel Armor” it was the hot high-tech innovation that pretty much revolutionized the way people world-wide would listen to music (and get their news; the automobile industry would engineer this technology for car radios as well). Those of us old enough to remember will appreciate the introduction of the transistor into our lives. But here’s part of the beauty of Sheckley’s speculation about how the transistor could be used. First, a brief bit of history. The transistor was invented in 1947–just the transistor–with no immediate practical application. But engineers in major tech corporations around the world attempted to adapt it to the radio immediately–in Japan, the US, and Germany–all were scrambling to find a commercially practical way for it to replace the bulky vacuum tubes used in radios and televisions. Everyone failed until 1954 when Texas Instruments introduced the first practical production line transistor radios. 1954. Radios became portable (with batteries as the power source, and that industry blossomed as well) and sans an electrical cord for the first time. They became part of the social consciousness of the public at large via exposure to magazine and newspaper articles all over the country…and in advertising everywhere. The transistor made the portable transistor radio an overnight sensation, selling billions from the mid-1950s through most of the 1970s when cassettes and other technologies replaced the transistor (the digital revolution was just around the corner).

But Sheckley’s story was published at the end of 1957, which means that with magazine lead time (at least four to six months, give or take), the inventory Galaxy had on hand, and whether or not the story was extracted from the slush pile (doubtful, but possible), that Sheckley wrote the story (following the time to come up with the idea, research it, and plot and write the story) either in very early 1957 or late 1956. No more than two years after the beginning of the transistor-fueled explosion hit the general public on a practical level with the first transistor radios. A revolutionary commercial application, mind you, that wouldn’t appreciably change the world for a few years yet.

So, as a science fiction author, what does Sheckley do with this transistor radio phenomenon. Two things. On the human level he speculates a “dating service,” such as they were at the time–but in this instance a very special sort of service–enticing the lovelorn (after payment) into wearing a miniature transistor radio device whereby an anonymous voice from the “service” whispers in the ear of the “customer” upon meeting a possible romantic partner, just the right words to insure a positive emotional response on the part of the other person (male or female). In essence, and for the time, a high-tech dating/match-making service (strictly on the up-and-up, of course–no “escort” service here). Therefore, the clumsy, tongue-tied, or shy are transformed into something they may want to be, and on the inside may be, but outwardly are not. How this transistor technology, used by Sheckley’s mid-1950s cutting-edge dating service plays out is the crux of the story. But the story doesn’t quite end there, for this is a Sheckley story. At the very end there is a chance meeting with our protagonist, years later, with the representative who sold him the original service. The service, the New York Romances service by name–has come up with a new “scientific” wrinkle. A set of personal and sociological matrixes whereby they can virtually guarantee a satisfactory romantic match, for New York Romances has followed our protagonist from his previous history and tracked his every move (how they do this is irrelevant–but we know how such things might be accomplished today, don’t we?).

As an example of how much of Sheckley’s blend of then-high-tech focused on the timeless search for love has progressed fictionally through the decades, we note that as recently as this year, 2011, new writers (whether they know it or not) are attempting to address the same concern, in strikingly similar, if not precisely identical fashion. The high-tech element is now borrowed from early Bruce Sterling, ones and zeros and the almost-magical possibilities arising therefrom and not the lowly transistor, and while the search for love is not from a dating service, the search for a one-on-one romantic rendezvous is still at the heart of the matter; see this review of the story “Perfection” by Jay Garmond from Redstone SF #11, April 2011–over half a century after “Gray Flannel Armor” appeared in Galaxy. The core use of technology to explore the identical theme is worth noting, thus, in part, this unusually lengthy introduction for which I beg forgiveness.

Listen now to Robert Sheckley’s simply wrought but in many ways profound tale, “Gray Flannel Armor,” aired as X Minus One‘s final series episode on January 9, 1958.

Play Time: 21:28